19. Landing on Cape Horn

1. Comandante

“Cape Horn”—these few words stir a sailor’s heart. This legendary cape stands at the end of the world, at the southernmost tip of South America, dividing the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.

Until the opening of the Panama Canal in the early 20th century, countless ships were wrecked and lost in violent storms around Cape Horn, less than 1,000 kilometers from Antarctica. The name “Cape Horn” has been passed down through generations as a symbol of terror: the worst place at sea, a devil’s cape, a sailor’s nightmare.

Even today, reaching Cape Horn in a small sailboat is a life-threatening challenge. Yet if successful, it is undoubtedly the ultimate joy and honor. Many have tried. Many have failed. Like Mount Everest for climbers, Cape Horn is a dangerous and ambitious goal for sailors, as well as a place of longing.

I did not want to merely pass by the Cape—I wanted to feel it beneath my feet. But people called the idea reckless and impossible. No one even tried to understand.

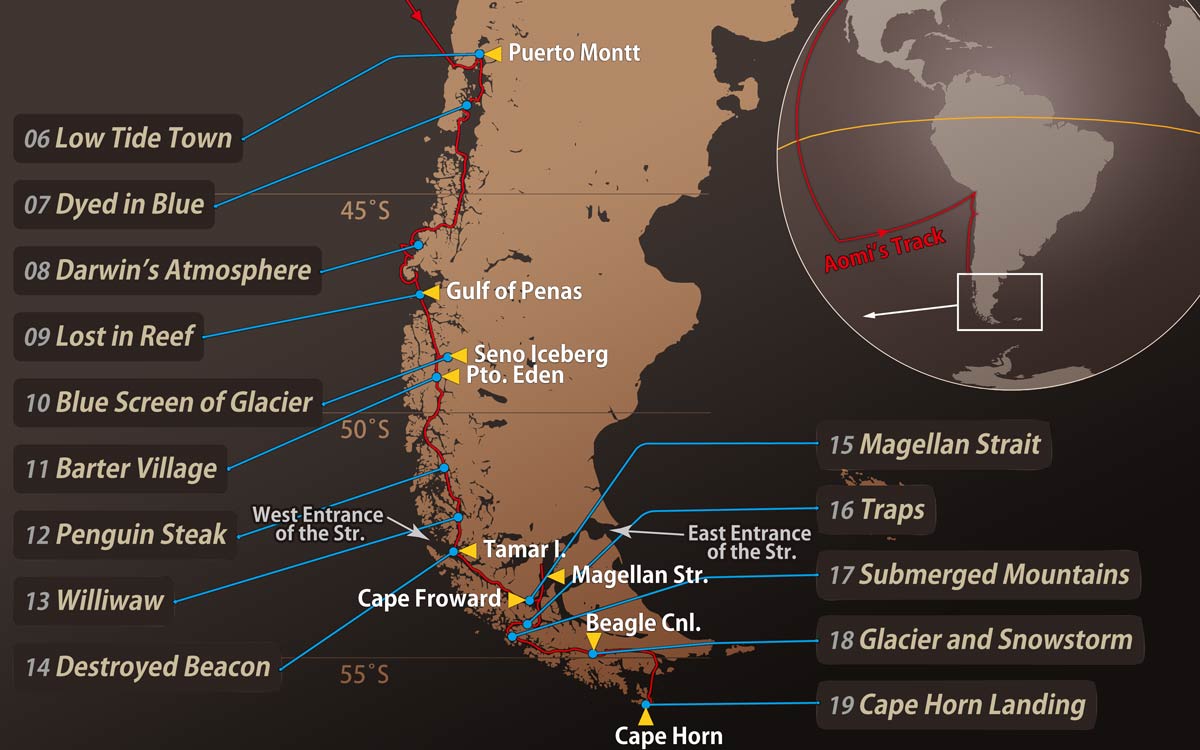

In early April in the Southern Hemisphere, Aomi arrives at Puerto Williams after sailing south through the Patagonian Archipelago. This, the southernmost town in the world, has a population of about 3,000.

As soon as I step onto the pier, I am told not to take any photos. The town’s unexpectedly large harbor is lined with gray warships and torpedo boats, with a red and white communications tower standing on a nearby hill. The Cape I am aiming for is just over 100 kilometers south of this naval base.

I visit the base headquarters to obtain detailed information about Cape Horn. After explaining my purpose to the soldier at the entrance, I am led into a room in the office. There sits the Comandante, the highest-ranking officer of the base.

An elderly gentleman in a navy blue uniform stands to shake my hand with a gentle smile. After introducing myself, I trace a course to the Cape with my finger on the nautical chart on the wall.

“No. For military reasons, passage through the Murray Channel is not permitted.”

The Comandante speaks firmly, then points to an alternative route. He gives detailed advice about dangerous rocks, currents along the way, and where to take shelter in case of storms. His attitude is unexpectedly friendly.

If possible, I also want to ask about a safe place to land on the Cape. But if I reveal that I plan to go ashore and he explicitly forbids it, my dream will remain just that—a dream.

I try to say it in a light tone, as if speaking to myself.

“If the weather is favorable when I pass the Cape, I would like to row a dinghy and go ashore.”

The Comandante’s smile vanishes. I bite my lip, thinking I said too much. After a brief silence, he begins to speak.

“In the waters around Cape Horn, strong winds blow constantly. A few months ago, a German boat sailed against the wind for four days but could not approach the Cape. Eventually, a huge wave overturned it. We, the Chilean Navy, rescued the crew and brought them here.”

He reaches across his desk and grabs the day’s weather map.

“Look. In this region, several low-pressure systems line up and move through almost every day.”

“But after a low-pressure system, a high-pressure system always comes, right?”

“No, you are wrong. No high-pressure systems will come. Only low-pressure systems will continue to pass one after another. There might be hope if it were summer, but it’s already April. Winter is approaching in the Southern Hemisphere, and the weather is extremely bad. The Chilean Navy can provide you with various forms of assistance, but when it comes to the weather in this region, there is nothing to do but pray to God.”

The Comandante continues in a serious tone.

“On your long voyage from Japan to here—halfway around the world—you must have experienced many storms. But the storms at Cape Horn are different…”

Before he can finish, I add,

“Near the Cape, the seafloor, which is 4,000 meters deep, suddenly rises to only 100 meters. This creates steep, triangular waves that are extremely dangerous even for a large ship.”

“That is correct. If violent, short-wavelength waves hit your boat, you could lose your sails or mast. Even if you survive the sinking, your tiny boat will be swept away, hit the rocks, or drift endlessly.”

The memories I do not want to touch, the sensations I do not want to remember, and the fear of the rough sea I have forgotten yet still carry deep in my body and mind — all of these come rushing back with his harsh words. The flood of feeling is so vivid that I almost shiver.

Still, he never explicitly said landing is forbidden. He probably does not even consider it possible for someone to go ashore alone.

In the evening, the Comandante drives a Toyota 4x4 to the harbor and looks down at Aomi from the pier.

“How did you get here from Japan in such a small boat? Please be very careful navigating toward Cape Horn.”

2. So Close, But…

A few mornings later, I arrive at a point 10 kilometers north of Cape Horn.

The legendary Cape, which I see for the first time, stands 425 meters high, its triangular peak basking in the sun beneath a rare, clear sky.

The Cape appears yellowish above the blue sea and, for some reason, looks a bit reddish in the morning sun.

Despite having dreamed of this scene for so long, I feel no excitement or joy. Instead, I fear the uncharted rocks and treacherous currents.

I cautiously watch the surface of the water ahead and take the helm toward the Cape, my nerves tight and my skin tense. Near Cape Horn, even a tiny mistake could bring the voyage to a fatal end.

When I reach the southern tip of the Cape shortly after noon, the sun shines brightly behind it, transforming the towering Cape Horn into a massive, breathtaking pyramidal silhouette. I raise my binoculars to the rock face, which looks strangely blackish green, with many rough protrusions.

As I continue along the cliffs below the Cape, the coastline unexpectedly recedes, revealing a small cove. This is one of the possible landing sites I have marked on the chart.

However, numerous black stones resembling human heads lie on the beach, and the swell and waves break violently into white foam. If I tried to approach with Aomi’s rowing dinghy, the waves would surely engulf and sink it.

Giving up on that site, I continue, and soon a hill of dead grass appears ahead. Below it, I see the small cove I have chosen as my next option.

I approach, raise my binoculars, and see the cove covered in brown seaweed. It is too dangerous to enter.

However, if Aomi anchors at the mouth of the cove and I row the dinghy over the seaweed, I might be able to land on Cape Horn.

After lowering the CQR anchor at the mouth of the bay, I check its hold by moving Aomi with the engine. When I apply full power, however, the anchor slips on the seafloor.

Fortunately, the wind is weak, and there is no danger of Aomi being blown away. I can land now. This opportunity may not come again until next summer. The time has finally come to fulfill my long-held dream. If I lower the dinghy into the water and row forward, I can step onto my dreamed-of Cape in just a few minutes.

On deck, I grab the edge of the dinghy and lift it. However, since the anchor doesn’t hold well, if a violent storm starts while I am ashore, Aomi would surely be swept out into the Atlantic Ocean, leaving me stuck on the Cape. Although I want to try different types of anchors, the autumn sunset is only a few hours away.

I look at the shore, just 150 meters away, and think, “Compared to the nearly two-year voyage from Japan, it’s just a short distance and will take only an instant to row to Cape Horn.”

So far, the weather is acceptable, and there are only small waves. No storm will come, anyway, and even if one does, the anchor will probably not slip. I have been preparing for years, but I might never get another chance if I do not act now.

I can realize my dream now. I want to achieve it no matter what. If I row the dinghy, I can step onto the long-awaited Cape Horn in just a few minutes.

But still, I cannot do it. If there is even the slightest risk of losing Aomi, I cannot proceed. No matter how much I want to realize my dream, attempting it without a plan to avoid fatal risk would be truly reckless.

With the landing site in sight, I make a difficult decision. I quickly draw the outline of the small bay and check the seafloor’s shape with a depth sounder. Then, with the wind suddenly strengthening, I leave the Cape as if fleeing.

The weather changes rapidly, and a storm is approaching.

3. No Matter What

During the four days of fierce gales at Cape Horn, Aomi quietly shelters in a cove 30 kilometers north, surrounded by mountains. I stay inside the cabin, cautiously preparing for my next attempt.

The success of the landing operation depends on proper anchoring technique. If the correct type of anchor is not selected and does not firmly set in the seafloor, the unmanned Aomi could be blown away by a storm during my landing.

In the small cove where the landing is planned, the CQR anchor dragged across the seafloor when Aomi pulled hard on it. This type of anchor is not suitable for the seafloor there.

According to the echo sounder’s ultrasonic reflection pattern, the seafloor is composed of hard mud, hard sand, or rock with some seaweed. Therefore, a Fisherman anchor must be the appropriate choice.

I simulate the landing using a sketch of the small bay I drew the other day, and I pack emergency rations, a hammer, a military-grade folding shovel, smoke bombs, a flashlight, and other essentials into a backpack. I also prepare a wetsuit to protect against the near-freezing seawater in case the dinghy capsizes during landing.

But is it truly possible to land alone on Cape Horn? Everyone I met in Chilean ports and naval bases called it a “reckless act.”

Earlier, even I thought it was impossible. But the more impossible it seems, the more my passion grows. I want to achieve this no matter what. I am determined to set foot on the legendary Cape Horn, the fearsome cape that has terrified sailors for centuries.

No matter how difficult the challenges seem, if I continue to work hard and develop ideas without giving up, opportunities will surely arise, and dreams can come true. There are things I should try, even if they seem impossible.

Over the past four months, I have sailed south through the Patagonian Archipelago, which spans 1,800 kilometers. During this time, I have anchored at night in the shelter of islands in typhoon-force winds. I have also rowed a dinghy to the shores of numerous uninhabited islands and landed. Was that not training for landing at Cape Horn?

Now, I have the experience and skills for the actual challenge. Landing on Cape Horn, once an impossible dream, has become a firm goal that I can surely realize.

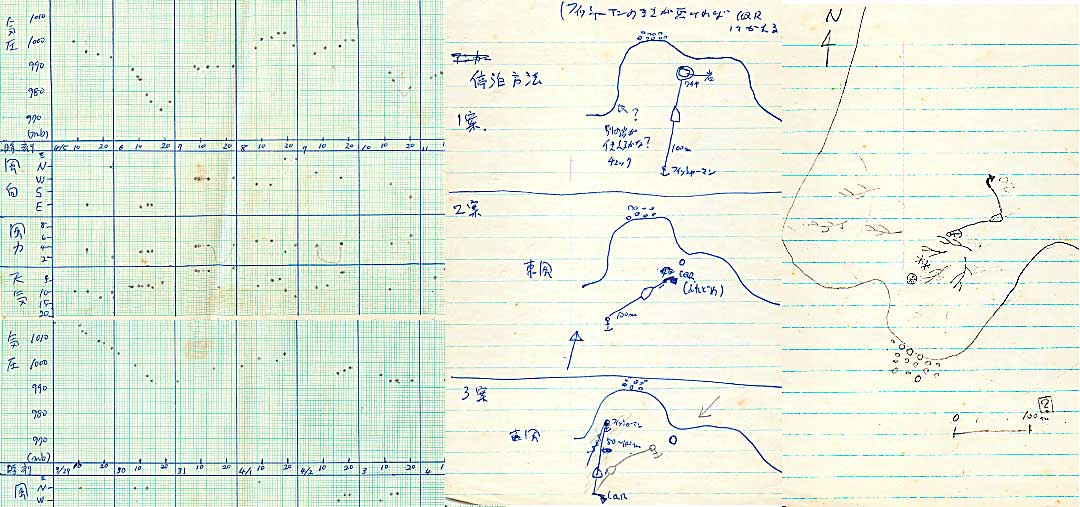

Since crossing the Strait of Magellan about three weeks ago and entering the southernmost part of the Patagonian Archipelago, I have been recording weather data daily on graph paper. This includes wind direction, speed, barometric pressure, and cloud cover, which are logged several times daily to study the weather patterns here.

For several days, the storm has been weakening; air pressure is stabilizing, wind speed is steadily decreasing, and wind direction is beginning to shift.

“Tomorrow, April 15, the Cape Horn landing operation will begin.”

4. Final Attempt

At 5:00 a.m., I open my eyes to total darkness. I have been in my berth for some time, listening to the roaring growl of the Williwaw blowing down from the mountains.

The hull shakes with the strong winds, the vibration echoing through my body. When I get up and open the hatch, the icy wind at 55 degrees South pierces my face. I shudder and close the hatch.

Is it still impossible today? Until yesterday, waves crashed on the rocks at the bay’s mouth, sending water columns skyward. But that is gone now. The wind has eased, and it is now a westerly, favorable for landing. There is no guarantee the weather will improve even if I wait longer. Another storm could come tomorrow.

“All right, let’s go. I’ll go anyway. If the wind picks up on the way, I’ll just come back.”

Raindrops, mixed with a gusty wind, begin to beat against the cabin window before I know it. After some hesitation, I decide to leave anyway. I quickly finish breakfast with canned fish, put on my yellow oilskin, and step out of the cabin. I breathe the cold air in and out, the landscape tinged blue just before dawn. Leaving in the morning is always refreshing.

At dawn, Aomi leaves the cove, her engine sounding light and lively. Holding the action plan in one hand, I pass the rocks and small islands exactly on schedule, maintaining a precise pace like clockwork as I head south.

If anything goes wrong and I cannot return to the cove before sunset, Aomi will drift in the dark, carried by wind and tide. She will probably collide with the islands; navigating around Cape Horn is tense, like walking a tightrope. One misstep, and it is all over.

Gusts of Williwaw, striking with a force I can feel as solid, blow against the single hoisted sail, tilting the mast again and again. There is a blue-black cloud ahead in the sky. What are those things hanging eerily from the clouds, looking like socks or arms?

Two hours after departure, Cape Horn appears on the horizon, its black rock poking into the sky. Unlike the clear outline of a few days ago, it is slightly hazy in the light rain. Is landing still impossible?

Sharp, triangular waves start to rise around Aomi and hit her continuously. She tries to approach the Cape, rocking as if to throw me off.

Suddenly, a small hole opens in the thick clouds, and a spot of sunlight shines on the dark landscape. The sunlight beams onto the triangular rock at Cape Horn’s peak. I hold my breath.

Three hours and fifteen minutes after my morning departure, Aomi arrives at the small bay where I plan to land, and I lower the sails. As expected, the bay is downwind of the Cape itself, with almost no swell or waves. I can go ashore!

I have several different anchoring plans depending on the situation. These will determine the success or failure of the operation. After reconfirming the wind direction and topography, I begin to execute the third plan in my notes.

The first step is to drop a Fisherman anchor at Point 1, a spot I marked in my notes, by carefully approaching the dense seaweed forest in the bay. Next, I turn the engine to full power, and Aomi pulls hard on the anchor line. As expected, the rope becomes so tight that I can almost walk on it. This indicates the anchor has held firm, securely fixed in the seafloor. Then Aomi hurries to Point 2, and I drop another anchor to ensure security.

Everything is all right; everything is perfect. Based on my experience, it will withstand winds up to Force 8. There is no need to worry; I jump for joy. The landing operation is almost a success.

As soon as I lower the dinghy from the deck onto the water, I row the 150 meters to shore, putting all my strength into the oars. Sometimes the wind whistles and blows hard, and small waves break white on the rocks. But such things do not bother me. I glide smoothly over the brown seaweed and reach a beach of large black stones.

“I have done it. I’ve finally done it. I’ve stepped on the legendary Cape Horn.”

My knees tremble with excitement. How did I reach the world’s farthest point, 55° 58′ S? With the Chilean and Japanese flags flying brightly, Aomi is anchored at Cape Horn. I am actually feeling the black rocky shore with my own feet. What could be more wonderful and exciting?

The scheduled hour passes as I walk around the shore, taking pictures of the black rock beach and picking up some souvenir stones. But I do not want to leave just yet. Now that I have landed, I want to spend a night at the Cape of my dreams and climb to the top of the rocky peak, 425 meters above sea level.

“Now I can do it. I can definitely do it. If I don’t do it now, I’ll never get another chance in my life. I want to do it. Somehow, some way, I want to.”

But no, it cannot be done, even if it is 99 percent safe. Proceeding without a plan for the remaining 1 percent risk would be foolish. No one knows when the next storm will hit or how bad it will be. If I do not hurry back to the starting cove, Aomi may never reach any cove.

I immediately row the boat back over the seaweed, get on board Aomi 150 meters off the coast, and start pulling up the anchor. But the anchor is very heavy. It feels as if the strength in my arms has gone.

The thick bandage on my left hand is soaked through, bright red. While cleaning up after breakfast, I cut my finger deeply with the lid of a can of fish. I could even see something white and solid deep in the wound. Can I pull up all 110 meters of rope and retrieve both anchors?

Heavy hailstones begin to fall from the leaden sky, rattling Aomi’s deck. The wind is picking up, too, and the next storm will surely come. I must leave the Cape as soon as possible.

Feeling pain in my injured left hand, I frantically pull the anchor rope with both arms, little by little. I stop several times as the bleeding increases, but I try my best to retrieve the anchor, feeling cold sweat all over my back.

The iron mass, weighing nearly 20 kilograms, finally appears on the water’s surface. To my surprise, the anchor’s claws are tangled in a ball of brown, plastic-like algae weighing dozens, maybe over a hundred, kilograms. No matter how hard I try, I cannot lift it by myself out of the water and onto the deck.

In the rising wind, I hurriedly open the stern locker and take out an 18‑inch machete, a long blade I prepared for this occasion in San Francisco. Lying on my stomach on the deck, I thrust my upper body out to sea and reach out one hand to chop off the ball of seaweed.

“Phew, I finally got the anchor up.”

I hoist the sails immediately and head for the cove I left this morning. Looking back, Cape Horn’s peak projects even blacker against the dark, hailing sky. The strong wind turns the sea white, and my face is wet with spray. But it no longer matters.

As if chased by a storm, I flee back 30 kilometers to the safe cove in the mountains. I look at my watch: ten hours and thirty minutes since departure. Everything is finished an hour ahead of schedule.

The Cape Horn landing operation is now complete.

A detailed explanation of this episode can be read here.

Hi! Any questions or suggestions about the content are greatly appreciated.

I’d also love writing tips from native English speakers. Since English isn’t my first language, if you notice any awkward phrases or anything that seems off, please let me know.

Thank you!

E-mail