12. Unknown Planet with Penguin Steak

What do you do when your mind panics, unable to process the sight of unknown creatures, otherworldly objects, or things you have never seen before?

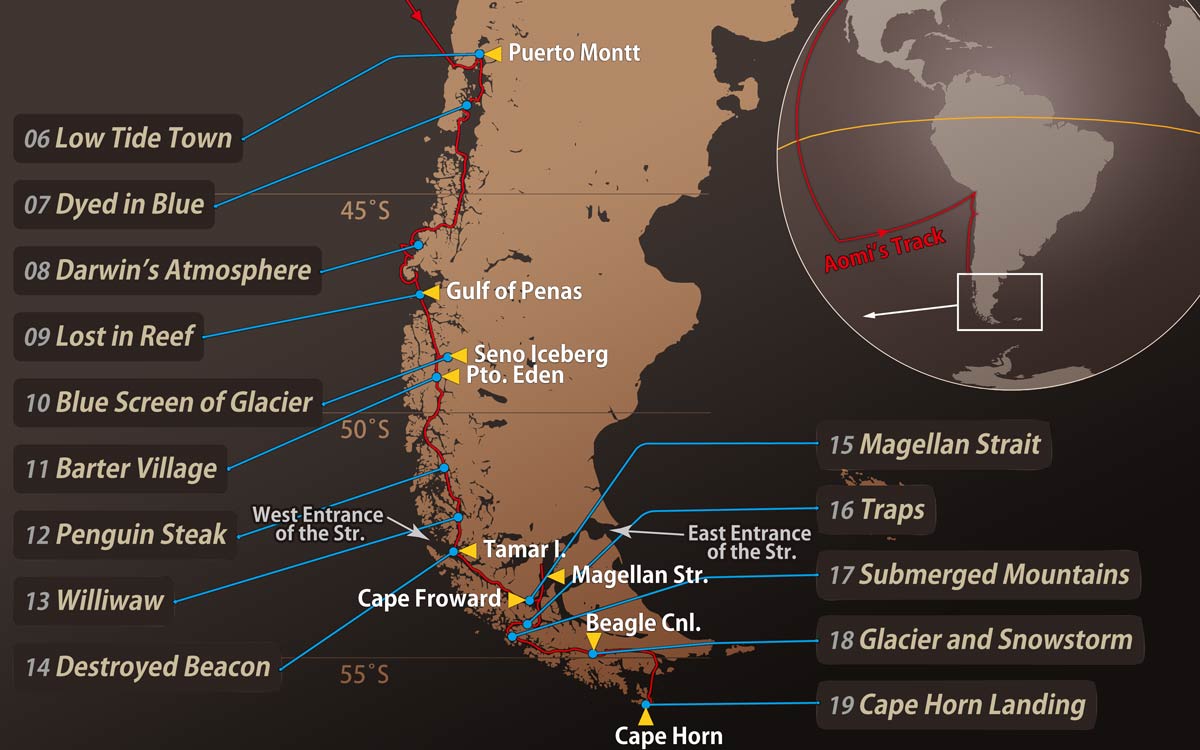

Aomi and I were sailing through a world that felt unreal.

It is an experience far from ordinary.

The landscape seems alien—unfamiliar and beyond understanding. I wonder whether it is frightening or simply too beautiful. But there is no doubt that it is awe-inspiring. I suddenly realize I have grown so used to this scenery that I no longer feel its true magnificence.

It is said to rain 330 days a year in the central part of the Patagonian Archipelago. Drenched in a deep, ghostly purple, the islands sometimes reveal strange rock formations that glow like coal beneath the dark, rain-filled sky.

Some slopes are bumpy, resembling burnt skin. Other mountains are covered in grotesque, tumor-like protrusions. Eroded by harsh wind and rain, the enormous bare rocks, lacking grass or trees, seem to reject the presence of life. It feels like the realm of demons, a terrible world of death.

At first glance, the islands appear only a few hundred meters above sea level. But when I consult the nautical charts, I find some are over 1,000 meters high. Do I feel differently at sea than I would on land? Has the enormous scale paralyzed my senses?

Long ago, the Andes rose from the seafloor. Glaciers carved deep valleys that later filled with seawater, leaving countless peaks behind as islands. Sailing through them aboard Aomi feels like flying over mountains in an airplane. It is as if the Earth’s long history seeps straight into my bloodstream.

No—it feels more like I have landed on another planet. The alien landscape and colors are unlike anything within the bounds of human imagination.

Before leaving Japan, I read Two Against Cape Horn by Hal Roth. The book’s photos and descriptions of the Patagonian Islands left a deep impression on me. Their appearance, as if created by the devil, made me feel Earth’s four-billion-year history and a power beyond human comprehension. But standing here now, I realize the actual landscape far exceeds anything the book could show. It is utterly incomparable.

According to the Chilean government’s travel guide, this is “the last wilderness beauty on Earth that no camera or words can capture.” Of course, I know my photographs cannot reproduce the strange shapes and hues of the mountains, covered in eerie, blistered skin like grotesque caterpillars and sometimes resembling giant organs resting on the sea. Though the images continuously stream into my heart through my eyes, I know they refuse to be captured by any photograph.

And yet, without knowing why, I find myself pointing the camera again and again. No. It is the scenery itself that demands it. I cannot resist. The precious film, bought by saving even on food, is quickly running out. With all my heart, I wish no more breathtaking sights would appear.

Still, each time I look up at the eerie mountains from Aomi’s deck as she passes between islands, an uncontrollable emotion, an irresistible impulse, surges within me.

After snapping several photos, I finally feel satisfied and go below to stow the camera. But when I return to the deck, the eeriness of the mountains startles me once more. I rush back for the camera again and again.

The scenery remains unchanged in the brief moments when I stow away the camera. Even so, why do I react as if seeing it for the first time?

I realize something unsettling. These incredible sights do not remain in my memory or in photographs. If I have never seen anything similar since birth, can I really memorize it instantly?

Guided by a stack of nautical charts, Aomi navigates south through a labyrinth of uninhabited islands, her stern trailing fishing lines.

In the late afternoon, with the mountains on either side shrouded in misty rain, I glance back and notice something caught on the line. I pull it and feel a strong tug. Have I hooked a piece of driftwood?

I begin reeling in the 30‑meter line with all my strength. The shape rises and falls in the water, getting closer to the stern. But when I look closely, I realize it is a bird.

I do not want to kill a bird just to eat it. But releasing it could injure me if it bites as I remove the hook.

“Still, it is a strangely round and fat bird. ”

After pulling it onto the deck, I take a better look. It has a black back, a white chest, and tiny paddle-like feet. Its surface feels more like fur than feathers, and the wings resemble flippers.

“Oh… is this a penguin?”

Unconscious? Its body is warm, but it lies completely still. If it wakes up, I want to play with it for a moment before releasing it, but there is no sign of movement.

Did it drown as I dragged it through the water? I place both hands on its white chest and begin chest compressions. But no one ever taught me any life-saving technique for penguins, and I am unsure whether it’s the same as for humans.

Checking my watch, I keep the compressions going, but there is no response. Just minutes ago, as I pulled it onto the deck, I noticed its unusually long neck, like that of a water bird. The shock of the fishing hook may have overextended its neck and broken a bone.

Since the penguin is already dead, throwing it back into the sea would be pointless. Above all, I do not want its life to go to waste. So I decide to eat it.

Carefully, I press the knife into the center of its belly. Inside are mostly organs and bones. There is only a small amount of muscle on the chest, and no fat beneath the skin.

I take two pieces of meat from the breasts. One is for a steak tonight, the other for stew tomorrow. The taste is…

Hi! Any questions or suggestions about the content are greatly appreciated.

I’d also love writing tips from native English speakers. Since English isn’t my first language, if you notice any awkward phrases or anything that seems off, please let me know.

Thank you!

E-mail