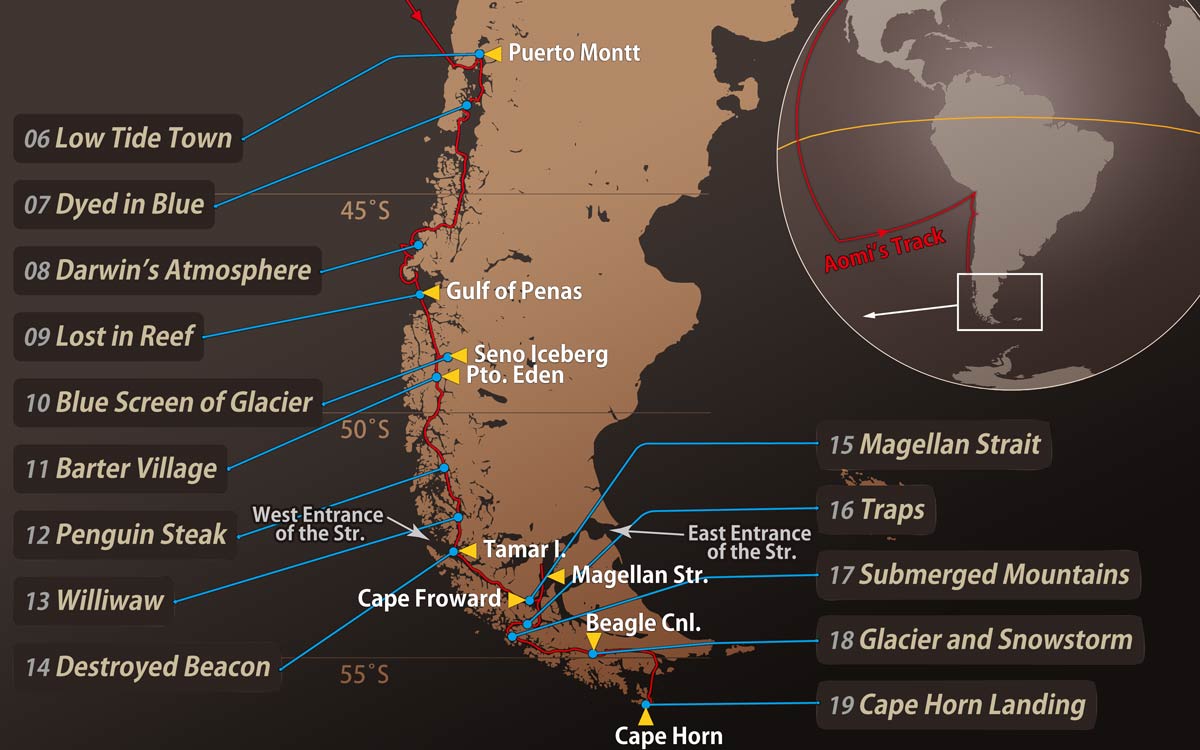

11. Barter Village

Sometimes, we wish we could stay in our warm beds forever. Other times, we wish we could forget reality and keep living in our dreams.

In a remote village in the Patagonian Archipelago, I may be dreaming another dream within the dream of the voyage.

1. Port of Eden

Puerto Eden (“Puerto Edén” in Spanish) sits on Wellington Island, near the center of the 1,800‑kilometer-long Patagonian Archipelago.

Steep, rocky, uninhabited islands rise along the surrounding waters. There are no human figures, livestock, or buildings. Even the nearest town lies about 500 kilometers away by sea. Puerto Edén is an isolated village deep within this vast uninhabited region.

Although the Spanish arrived in South America in the 16th century, the Alacaluf tribe had lived here long before.

“What? Puerto Edén? It’s a native village and a crazy place. Money isn’t accepted—everything is bartered. Also, your belongings might be taken without you even knowing, but not with bad intentions. They simply do not distinguish between what’s yours and what’s theirs.”

I heard these rumors on an earlier stop in a Chilean town.

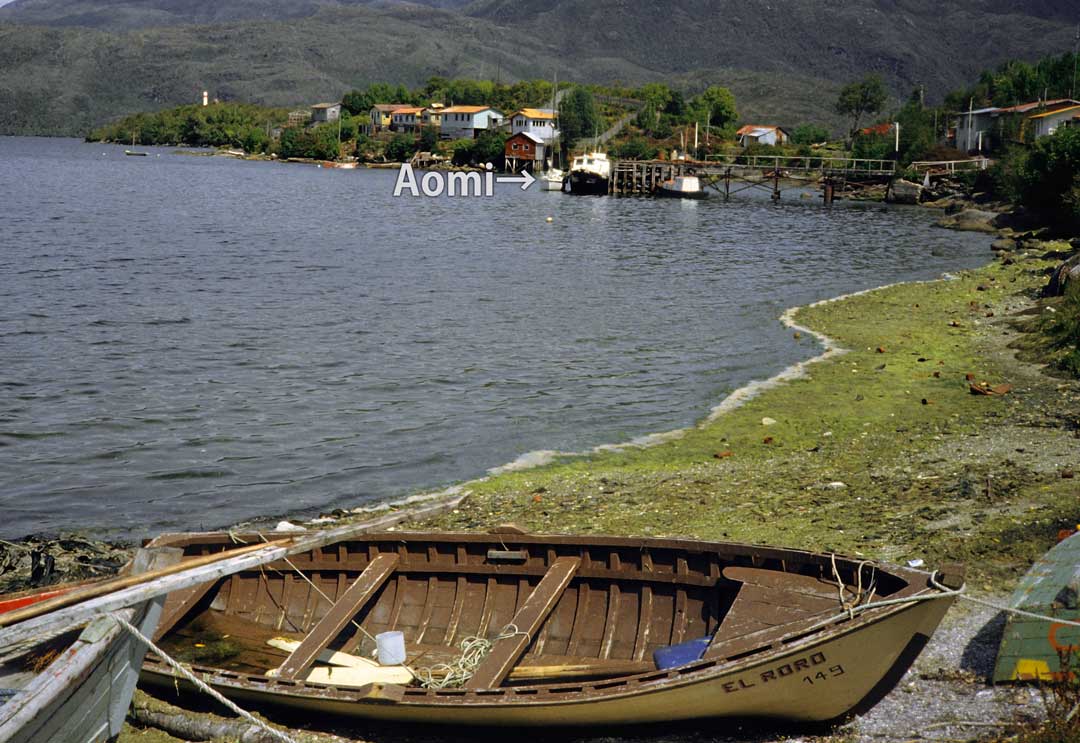

By the time I arrive at the desolate Port of Eden, I am already in the ninth week of my voyage through the islands. I dock Aomi at a small wooden pier and step onto the island’s quiet shore.

“What a lonely village.” A few shabby houses stand in the light rain, and only one path resembles a real road. The ground is swampy, with sparse grass and trees struggling to grow. In some places, my boots sink so deep I cannot walk. It is a cold, remote land near the 50th parallel south.

It has been four weeks since I last set foot on an inhabited island. To find out how to get fresh meat and vegetables, I go to the police station. In front of a one-story wooden building that looks like a house, a Chilean flag flutters red, white, and blue on a long pole.

“The climate here is too cold for growing vegetables, and meat is quite rare. People usually have it only once a month. Supplies arrive by ship every two weeks. Would you be able to wait until then?”

At the door, a tall man named García responds apologetically. In contrast to Chilean city police, who typically wear grass-colored uniforms and carry submachine guns, he is dressed casually in a sweater, like a civilian. It is surprising that even four Carabineros (Chilean police officers) have been assigned to this tiny village of just 330 residents.

To get some eggs, I walk through the village, my shoulders damp from the light rain. In the blue bag on my back are a few slightly worn pants and sweaters. I have heard that the villagers are interested in used clothing, so I plan to trade them for eggs.

Eventually, I find a shabby house that looks more like a storage shed. Several chickens run around on the ground nearby. As I approach, a young man slightly opens the broken door, and his face appears. I try to speak to him in broken Spanish.

“I want some eggs. I need them for my voyage.”

“Nothing for you.”

He not only looks unfriendly, but also seems to have an unpleasant personality.

“Um… about some clothes…”

At this, his manner changes, and he invites me inside. The room has only one tiny window, like a prison cell, and is so dim it feels like evening. There is almost no furniture or decoration. It feels like a poor and gloomy home.

The man calls his wife. Together, they pick up the used clothes, inspect them thoroughly, and say:

“What the hell? I don’t want these rags.”

I am speechless. How “luxurious” they seem! These clothes may be old, but they are not dirty or torn. In fact, they are wearing better clothes than I am. I feel embarrassed, as if they are making fun of me, but I keep trying with gestures and manage to exchange them for eight muddy eggs.

2. Fix It!

The next day is another gloomy one with light rain.

The journey through the islands to Cape Horn will take several more months. Since Aomi uses her small diesel engine each time she enters or leaves the bays along the islands, I need to refuel here. According to the Carabinero, some residents keep their own diesel supply.

I begin walking along the coast toward the house I was told about. A few broken boats lie scattered on the rainy gravel beach, making the scene feel even more desolate.

Soon, I arrive at a house by the sea that is slightly more refined than the others, with larger glass windows. This family may be “wealthy” by the standards of this village.

“¿De dónde viniste?” (“Where are you from?”)

“De Japón.” (“From Japan.”)

The conversation begins at the entrance. I explain that I have been away from home for a year and a half and have been traveling along the Chilean coast for about six months. I also mention that I need diesel fuel.

“What was your job in Japan?” asks the older, short man who seems to be the head of this household.

“Developing computer software.”

Then he says, in front of the whole family, with a know-it-all attitude:

“Oh, then it must be something electrical—you can fix it. I have a Yamaha generator that won’t start. Fix it.”

I reply, frustrated:

“Computer software has nothing to do with electrical repairs. Besides, if it won’t start, it’s probably an engine issue, not electrical.”

This village lacks a regular electricity supply, so at night, small generators start up with a rumble in the Carabineros’ quarters and in the homes of a few wealthier families.

“Anyway, you’re from Japan, an electrical engineer, right? Fix the generator, and I’ll give you the diesel fuel for free.”

Though frustrated by the misunderstanding, I am familiar with engine repairs. I grab my wrench and begin disassembling the generator beneath the narrow overhanging roof, sheltering from the light rain.

Two hours later, when the tiny two-stroke engine finally starts with a pleasant growl, everyone gathers in a room, connects the wires from the generator to a bare light bulb, and starts playing cards.

I return happily, carrying 30 liters of fuel and a bucket full of mussels and clams.

3. So Many Crabs

By morning, news of the generator’s repair has spread throughout the tiny village. People here live by fishing, collecting mussels and clams from the sea, and smoking them. But surprisingly, their small boats are powered not by sails or oars, but by American and Japanese outboard motors.

It feels unexpected to find such modern equipment in this isolated village. But unfortunately for the villagers—and for me too—most of the motors are broken.

Soon, people begin to come to Aomi, asking for help with repairs. The outboard motor is an essential tool for their livelihood. One unit costs more than what they earn in a year, making it a precious possession. Since there is no way to repair them in the village, their frustration must run deep. Reluctantly, I decide to help.

After two full days spent fixing motors, I find myself at a loss. Every time I fix one, another one appears. I quickly realize that at this rate I will never be able to leave. I pack up my tools, shake hands with the carabineros, put on my boots and oilskin, and try to start Aomi’s engine.

“All right, let’s go!”

Still, for some reason, the engine will not start. No matter how hard I turn the starter handle, it just spins and spins without firing.

Eventually, departure is postponed. Now it is time to repair my own engine. Disassembling the exhaust valve and piston is a tough job.

“Heaven may have punished me for trying to escape from the village.”

The repairs continue into the next day. The cabin floor and my hands are covered in oil. As I look out the window, the sea presents a gloomy, rainy scene. On the gray surface of the water, a shabby little boat emerges and approaches Aomi. An old man in a dirty sweater, soaking wet from the rain, is on board.

He makes a clattering sound on Aomi’s deck as he places several large red crabs, known as centolla, an expensive delicacy in the Patagonian Archipelago. He says they are a thank-you for fixing the outboard motor. Even one would have delighted me, but he gives me five of these fine crabs.

Surprised, I hastily take out the American powdered milk and soup mix I had carefully stored and offer it to him.

From now on, there will be a crab feast every day. Will I get sick from eating too much? No, it is fine to eat crab until I get tired of it. After all, I have come all the way to a place where crabs are plentiful.

And when I think about it, the exchange seems natural. People from a country that produces outboard motors repair them. People from a region rich in crabs offer them in return.

A week after arriving, Aomi leaves Puerto Edén.

Honestly, I do not want to go. The hard voyage will begin again: the dangerous passages where rocks lie hidden by constant rain; the fear of not reaching the next bay before nightfall; and the nights spent at anchor, anxious about fierce winds in the pitch-black darkness. All of this will return. If I could, I would stay in this Garden of Eden.

But I cannot. It is already February, and autumn is approaching in the Southern Hemisphere, even though I am only halfway through the Patagonian Archipelago. I must keep moving south, or I will reach Cape Horn in winter.

With determination, Aomi and I set out once more, into the unexplored seas ahead.

Hi! Any questions or suggestions about the content are greatly appreciated.

I’d also love writing tips from native English speakers. Since English isn’t my first language, if you notice any awkward phrases or anything that seems off, please let me know.

Thank you!

E-mail