07. Dyed in Blue

When you move far away or start a new life for work or school, your past days can feel like a distant memory, or even a dream.

I found myself in another world of blue, surrounded by a sea of endless islands.

It is like a dream. No, like a painting.

Islands stretch out like a blue mirage on a blue-black sea. The snow-capped Andes stand out as if carved from a plate of dark blue. Have I stepped into a painting of blue? Even time seems suspended. Aomi glides swiftly through the blue, her white sails shining as if part of the painting itself.

And yet, I feel at a loss. Even as I try to imprint this clear, transparent landscape of mountains, sea, and islands into my memory, it feels too beautiful to hold. Surely no camera can capture this pure, soul-stirring blue. What can I possibly do, surrounded by this landscape that dyes my heart so deeply blue?

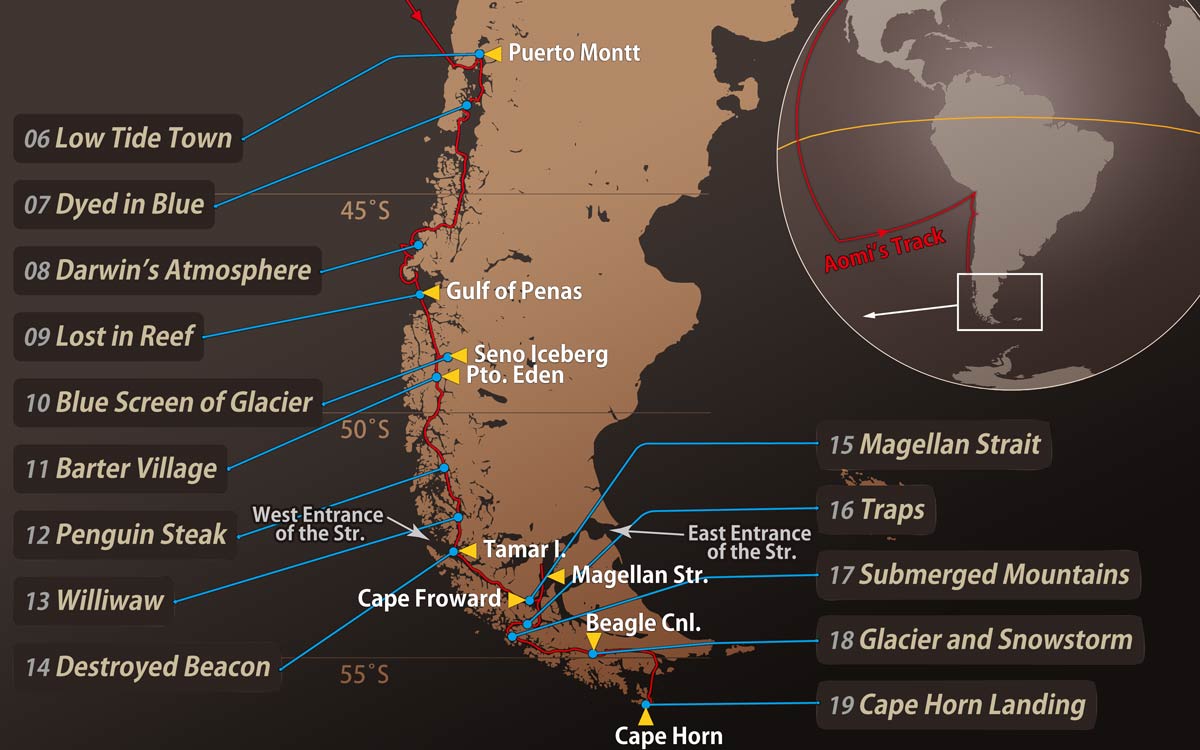

After leaving Puerto Montt, the northernmost city in the Patagonian Archipelago, Aomi sails south through the sea of islands toward Cape Horn, the southern tip of South America.

Each morning, I wake in a bay, breathe the fresh air, prepare breakfast, pack a lunch, raise anchor, and set sail. By nightfall, Aomi arrives at an island several dozen kilometers south, anchoring in a sheltered cove. Later, I finish dinner, spread out charts and Sailing Directions in the cabin, and spend hours planning the next day’s course.

I carefully study the navigation charts published by the U.S. Department of Defense, marking hazardous points in red ink. I compare nearly a hundred charts from the U.S., U.K., and Chile, checking the reliability of topographic and bathymetric data, selecting the next day’s anchorage, and drawing a course line in soft pencil. I also mark potential anchorages for emergency shelter in case of sudden weather changes. It feels as if I have come here not to sail, but to do paperwork.

In truth, sailing through the archipelago is more difficult than one might think. With so many islands crowded together, it is easy to mistake a cluster of them for a single large island, and feel utterly lost. Some islands differ in shape or position from what is shown on the charts, and many shoals and rocks remain uncharted. The Chilean charts are especially interesting; many newly discovered reefs are handwritten in by the issuing office after printing.

The U.S. Sailing Directions, which contains navigation information on the Patagonian Archipelago, includes a warning that is hard to believe:

“In general, the soundings appearing on the charts are of a reconnaissance nature. Mariners proceeding through this area should use the utmost prudence in navigation.”

In addition, the U.S. charts for the Patagonian Archipelago warn:

“The area covered by this chart has not been completely surveyed.”

Will I make it to Cape Horn without running aground?

Suddenly, I realize that all inhabited islands lie behind me, and the vast region ahead is entirely uninhabited.

The fishing line trailing behind Aomi frequently catches fish as she sails. They are about 50 centimeters long, with large pectoral fins and thick bones like horse mackerel. The 30‑meter line splits into a Y-shape, with small plastic squid-shaped lures at each end.

Some days, fish bite both lures, and I catch two at once. In crowded cities, there is a joke: there are more people fishing than fish in the water. But here, in these uninhabited waters, I can fish without limit.

This allows me to save much of the canned food I could not afford to buy in sufficient quantity. I fillet the fish into three pieces, eating some as sashimi and grilling the rest with a sprinkle of salt. One freshly caught fish is enough to serve as the main dish for two days.

From Aomi, anchored in a quiet cove, I row ashore in a dinghy and step onto the uninhabited island with a touch of fear. Birds sing in the dense forest, and as I walk along the beach, I spot small crabs crawling in the cracks between the rocks. Countless tiny fish gather where the sparkling stream pours into the sea. As I approach, they suddenly dart away, leaving only crystal-clear water behind.

At low tide, standing on the beach, I am surrounded by the strange chorus of breathing shellfish, something I had never imagined. The bustle of the city and the noise of cars feel like another world, so distant that I can hardly recall city life.

As I row the dinghy along the shore, I look into the water. It is as clear as tap water, almost as if I could drink it.

The sandy bottom is clean and dotted with the breathing holes of shellfish. Forests of green, brown, and white algae resemble plastic. I see hills dotted with sea urchins and white rocky peaks, like looking down at a landscape from an airplane.

Looking up from the water, I spot strange orange rocks, bright under the sunlight as if painted. The trees on the island are such a piercing green that it actually hurts my eyes to keep looking at them.

In the clear blue expanse of the northern Patagonian Archipelago, I breathe in the fresh air, feel the currents through the tiller in my hands, listen to the tides, and sense the sky, sea, and Andes in my heart and on my skin.

I am glad I came. So glad I came by sailboat. Because here, every day brings experiences I could never have imagined in the city, experiences I had not even known existed.

Hi! Any questions or suggestions about the content are greatly appreciated.

I’d also love writing tips from native English speakers. Since English isn’t my first language, if you notice any awkward phrases or anything that seems off, please let me know.

Thank you!

E-mail