09. Lost in the Reef

Sometimes you realize you have made a serious mistake, and that leaves you in the worst possible situation. You feel utterly hopeless, convinced that survival is impossible and everything is over. Yet even then, you may still try to find a way out.

That was what happened to me when I crossed the Gulf of Penas.

1. Reef’s Gateway

The Gulf of Penas is indeed well known for its danger.

“Golfo de Penas, muy peligroso.” (“Gulf of Penas, very dangerous” in Spanish).

That was what the people in the Chilean ports told me, moving their palms up and down to show how high the waves were. Dangerous rocks and shoals also dot the southern side of the gulf. They said that “penas” means “pain” in Spanish.

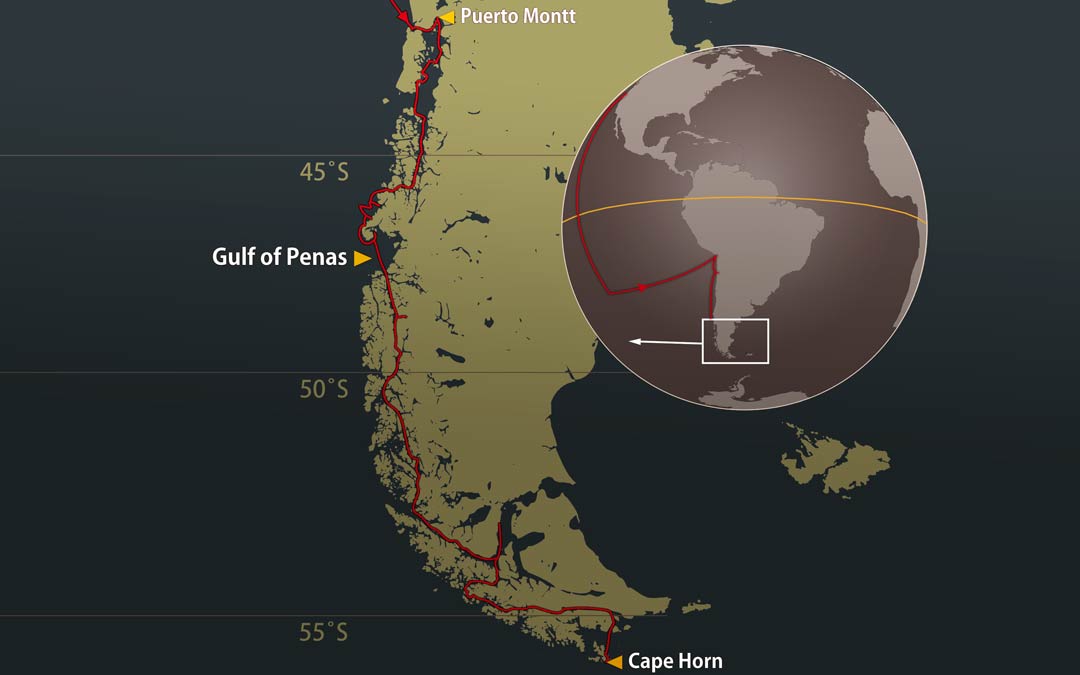

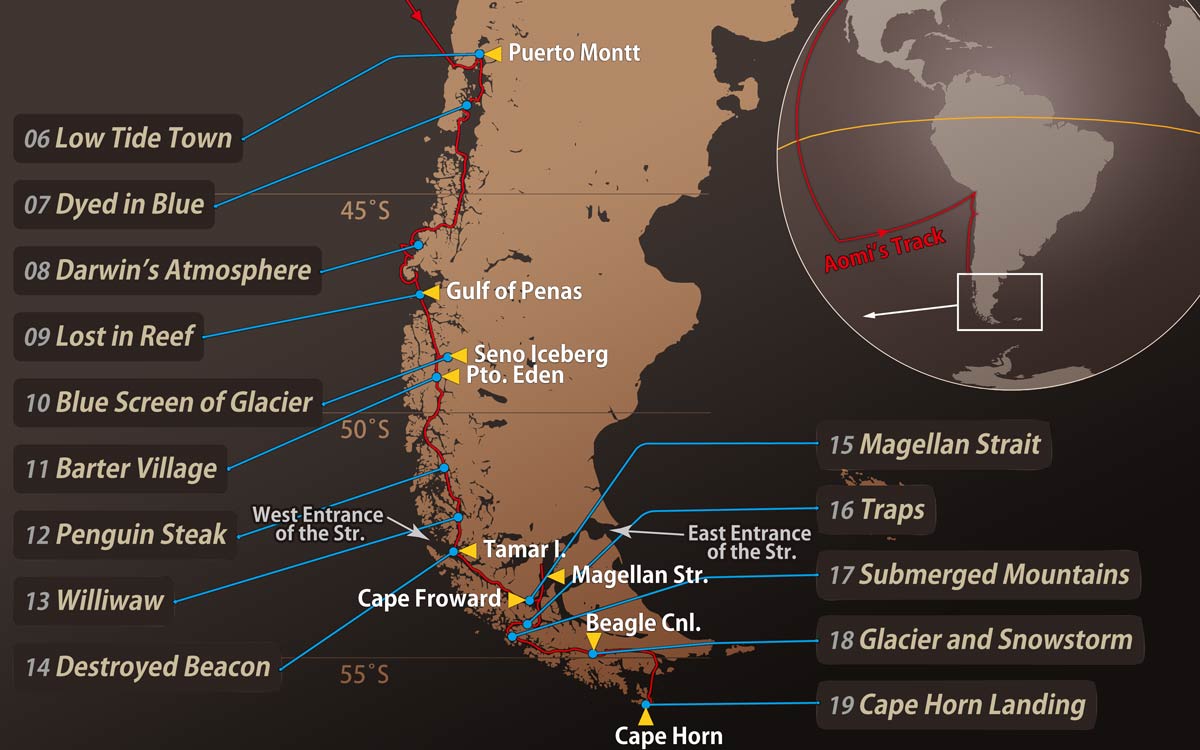

Eight weeks after entering the Sea of Islands, Aomi reached the Gulf of Penas, a vast break in the Patagonian Archipelago. Here, the long chain of islands and fjords along the west coast of South America is interrupted. After sailing 80 kilometers south across the gulf, the islands begin again.

At 4:00 a.m., I open my eyes in my cabin berth. Gusts of wind howl in the darkness across the Barroso Inlet, on the north side of the Gulf of Penas. Heavy raindrops occasionally strike the deck. I open the hatch and look up at the black sky. Through a hole in the clouds, a single star shines.

What should I do? If visibility is poor due to rain, Aomi could hit a rock upon reaching the southern side of the Gulf of Penas. I need to see at least 20 kilometers ahead. Only then can I take bearings from nearby islands to determine Aomi’s position and stay on a safe course.

I finish breakfast, step out on the deck, and find the rain has stopped. The morning is bright and overcast. The wind shifts in strength as if trying to threaten me. But it is a northerly wind, favorable for sailing south across the bay. Under the cool, clear sky after the rain, the Andes look as if cut from a dark blue glass plate, set between the gray sea and sky.

I know I have to go. The Gulf of Penas is known for bad weather. No matter how many weeks I wait, the skies may never clear. This might be the best weather I’ll get.

I quickly raise the anchors, pulling in a total of 110 meters of rope, then take the helm and sail out of the bay. Soon, Aomi catches the strong following wind and rushes into the Gulf of Penas. But the waves are fierce, tossing her repeatedly. I must reach the southern side of the bay before nightfall. A summer day here, at 46 degrees south latitude, begins around 6 a.m. Chilean time and lasts until after 10 p.m.

Before long, the gulf’s northern shore, which Aomi had just left, fades into the distance. The crisp, dark blue mountains blend into the cloudy background behind me. Everything turns gray: sky and sea, merging into one.

Four hours after departure, as Aomi approaches the center of the bay, the waves grow higher. Sharp, triangular wave crests repeatedly strike Aomi’s stern, breaking upward and cascading over my head. The hull rocks violently, up and down, side to side, making it hard to hold course. It feels like riding a wild horse. I grab the lifeline and nearly fall.

Still, Aomi pushes forward through the gray sea, her sails nearly tearing in the strong following wind. The sky is dark, but my mind is clear. At this pace, I should reach the southern edge by nightfall. I am strangely glad to be crossing the infamous Gulf of Penas without any problems. Everything is going smoothly, and there is no trouble in sight.

My only concern is Aomi’s current position. Eight hours have passed since departure, yet nothing is on the horizon. Strange. By now, the islands on the southern side should be visible.

Rain begins to fall again. I stare ahead, but all I see is a dull gray sky and sea.

2. Rain Blindfold

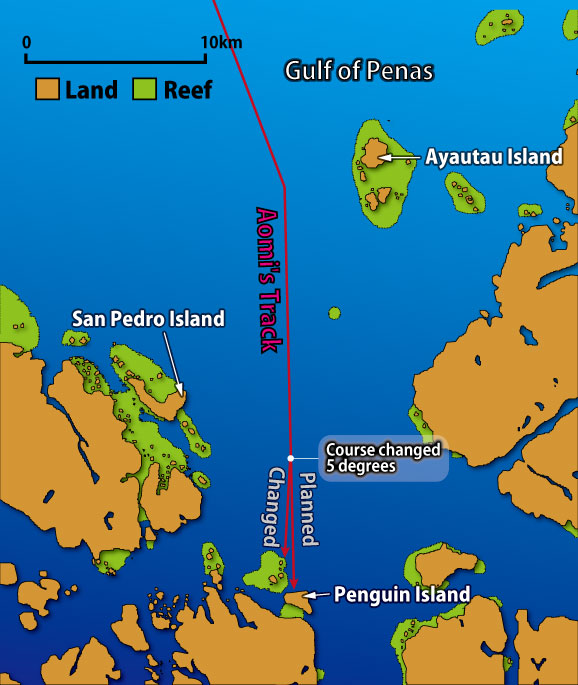

The rain begins to ease. At the same time, the visibility improves, and, as if by magic, a large, pyramid-shaped island appears to my left. It must be Ayautau Island, which rises 227 meters on the south side of the gulf. Ahead of me, in the clear air after the rain, I can also see the distinct shapes of the islands, like dark blue cutouts on the horizon.

I have finally crossed the Gulf of Penas, notorious for its bad weather. Everything is going according to plan.

As I think this, the sound of the rain intensifies. Ayautau Island, and the blue islands that had been so close before me and so clearly visible, now disappear as if they were an illusion. Once again, it is a gray world of cloudy sky and sea. The rain is so heavy that even the wave tops 100 meters away are invisible.

When will the rain stop? It is so intense that I feel the pressure on my head, like standing beneath a bathroom shower turned to full blast.

Though countless islands and dangerous rocks lie ahead, I cannot see them because of the rain. I do not even know where I am. If I keep going, it would not be surprising to crash into rocks at any moment.

I lower the sails and try to stop Aomi. But in the strong wind, this is completely useless. Even with all the sails down, the wind pressure on the mast alone is enough to push her forward.

There is nothing more I can do. No way to stop. No way to turn back to windward. No matter what I do, there is no hope of resisting the overwhelming power of the wind. Aomi can only be swept toward the dangerous rocks. It is like being carried by a conveyor belt moving in one direction, or rather, being carried by fate and time, which cannot be stopped or reversed.

Leaving the helm to the handmade wind vane (a wind-powered automatic steering device), I go down to the cabin and stand before the charts.

Even if Aomi’s current position is unknown, with luck, she will drift to the destination, Penguin Island. But if the course is off to the left due to poor visibility in the rain, she will pass to the left of the island without realizing it. On the other hand, if the course is off to the right, she could end up in the reef zone just before the island. It is a dangerous game I cannot escape.

Before I know it, the rain has stopped, and I have a clear view ahead. Next to Aomi is a small island. This distinctive crescent shape must be San Pedro Island, 10 kilometers from Penguin Island. Through my binoculars, I can see every single tree. I quickly aim my compass and sextant at the island, measure the azimuth and elevation angles, determine Aomi’s position, and draw a course line to Penguin Island on the chart.

A few minutes later, the rain starts to fall again, immediately obscuring the clear view. Penguin Island is now only 8 kilometers away. Standing on the deck and taking the helm, I sail through the gray world of roaring winds, as if blown away, pushed only by the wind against the bare mast.

The outline of Penguin Island, Aomi’s destination, appears faintly in the sky ahead. Compared to the course line I have drawn on the chart, it appears 5 degrees to the right. Strange, I wonder, but without considering why, I adjust my course five degrees to the right.

Knowing that a slight deviation to the right would take Aomi into the reef zone, I steer directly toward the outline of Penguin Island. The gray silhouette, slightly darker than the sky, suddenly turns black-green, and I notice whitecaps breaking on the island’s shore.

Whitecaps, breaking waves?

Compared to the size of the waves, it looks more like a giant rock than an island. Something is different. Something is wrong. The depth sounder drops from 40 meters to less than 15 meters.

“Watch out!”

3. No Way Back

No photo here. Surviving was all I could do.

Suddenly, the rain begins to ease, and the outline of a large mountain appears beyond the island I have been aiming for.

“That is it. That’s the real Penguin Island.”

Due to the poor visibility caused by the rain, I have misjudged all distances and sizes, and I have ended up sailing toward the rocks in the reef zone.

Aomi is now unmistakably within the reef zone, marked in green on the charts. Beside the hull, high waves crash against the rocks just above the surface, sending up violent plumes of spray. It is powerful enough to shake my entire body. Never before have I felt the power and majesty of the sea so deeply. Once, I thought that even if Aomi ran aground and broke apart, I might still be able to save at least my own life. But here, grounding will mean the high waves lift Aomi and slam her against the rocks, with me still on board. She will be destroyed and sink in an instant.

Even so, turning back is now clearly impossible. There is no way to resist this vast power of the wind and waves. No matter how hard I try, I cannot turn back to windward.

Since I can’t go back, since I can’t turn around, I have no choice but to pass through the reef zone. Even if the rocks are so tightly packed that there is no gap to slip through, there is no alternative!

Once I make up my mind, I concentrate fully on the sea surface. All around Aomi, high white-capped waves are breaking violently. Yet there is a subtle difference between wind-driven waves and those crashing over submerged rocks. I can just barely detect the presence of underwater hazards. No—I must detect them. I must know exactly where the rocks are, or I will lose Aomi and my life.

Each time the waves lift the hull, I peer ahead, searching for danger, and steer Aomi in a weaving course, dodging the rocks one by one. When the depth sounder reads shallower, I quickly turn the bow to the side to avoid the rocks lurking just below the surface, cold sweat running down my back. Aomi, struck again and again by sudden breaking waves, tries to get through the foaming reef zone as if blown away by the gale-force wind.

Then, before I realize it, the depth sounder reads more than 40 meters again. She has now entered calm water, often found on the lee side of reefs.

Approaching Penguin Island, still covered by wind and rain, Aomi enters the back of the island and drops anchor.

“That was too close! What a relief.”

The vivid images of white foaming shallows and black rocks sending up clouds of spray beside Aomi are burned into my memory. They will never fade.

I am shivering from fear, and from the cold rain.

Hi! Any questions or suggestions about the content are greatly appreciated.

I’d also love writing tips from native English speakers. Since English isn’t my first language, if you notice any awkward phrases or anything that seems off, please let me know.

Thank you!

E-mail