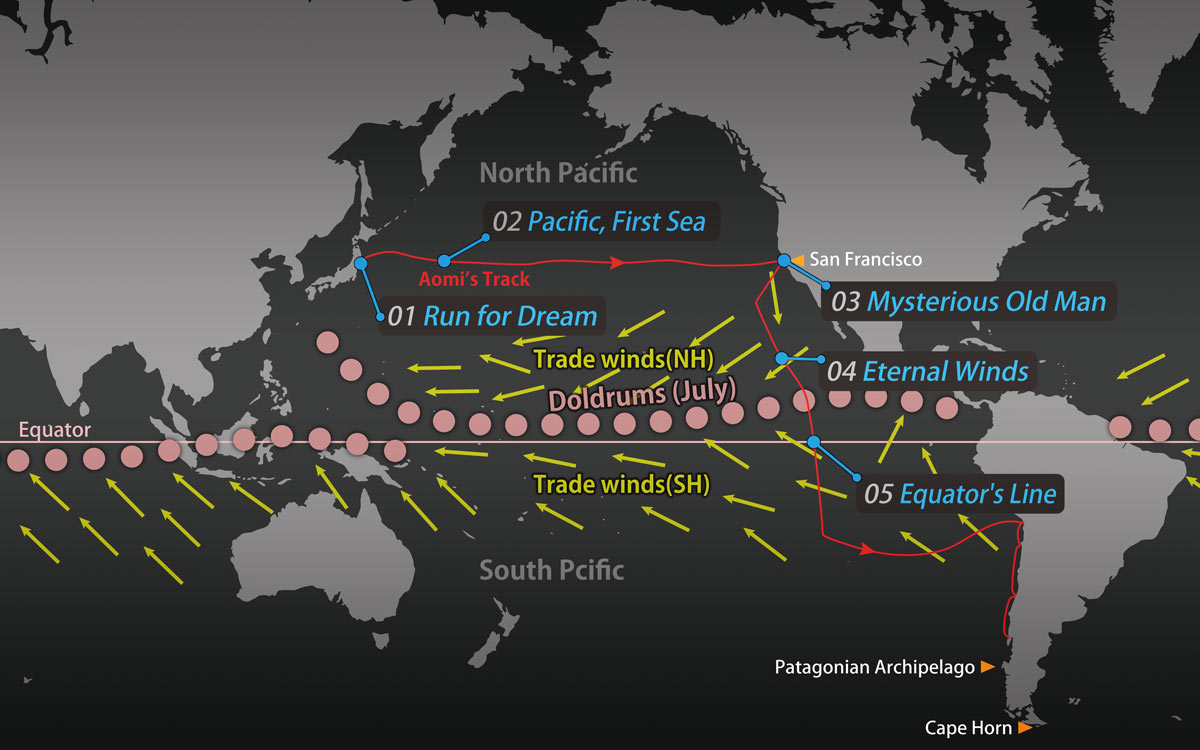

02. Pacific: My First True Encounter

We often assume we understand things like other people’s pain, the taste of exotic food, or the customs of a foreign land. But when we experience them ourselves, we are often stunned by how little we actually knew.

That is exactly how I feel as I first sail out into the vast Pacific.

1. The Storm Strikes

Nothing surrounds me but the endless sea.

At the end of each summer, typhoon waves roar and crash onto the shore. But now, even larger waves are striking my small sailboat, Aomi, one after another.

Like most sailboats, Aomi tilts as she cuts through the waves, her white sails billowing in the wind. With each wave that strikes her side, she leans further—almost to the point of capsizing. One moment, a massive wave lifts her several meters high; the next, it slams her down into the valley between the waves.

Inside the tiny, cramped cabin, everything flies around: magazines, harmonicas, dishes, onions, even sharp knives, all threatening to hit me. The cabin shakes so violently that it feels like an earthquake. Could there be a typhoon nearby?

My head throbs with pain. Dizziness and nausea overwhelm me. The pain in my stomach is so sharp that I can trace its exact shape. Lying in my narrow berth inside the cabin, I feel the days slipping by, one after another.

At the stern, a handmade wind vane steers Aomi automatically as she pushes forward, resisting the waves.

Aomi is strong, but I am too weak. Yet back in Japan, everyone thought I would never get seasick.

Perhaps my muscles have been unconsciously fighting the motion, draining my strength even as I lie in my berth. On top of that, I have not eaten in two days, ever since the storm began.

Exhaustion and hunger have drained me to my physical limit. Even lifting my hand to check my watch feels impossible.

I need to eat soon while I still have the strength to move. If I do not, exhaustion will overtake me and I will die.

With the last of my strength, I get up from my berth. Sitting on the floor, barely the size of a tatami mat, I open a can of peaches.

Afraid my stomach might reject them, I carefully spoon the peaches into my mouth, trying not to hit my nose as my body moves violently up and down with the cabin floor.

To my surprise, the peaches taste incredible. Before I know it, I have eaten the entire can. I have never been so impressed by canned food in my life.

Once my hunger is satisfied, I press my nose against the acrylic pane of the cabin’s tiny window and stare out at the raging sea. It feels like looking out from a mountain hut, but instead of mountains, I am surrounded by towering waves.

Everywhere, steep slopes, valleys, cliffs, and peaks rise and fall, reshaping the seascape in an instant. I never imagined that the waves tower so high, and that the sea is an entirely different world from the land.

The journey to San Francisco, my destination across the Pacific, stretches over 8,000 kilometers. That is one-fifth of the distance around the equator, yet I already feel weak at the very start.

Can I really cross the vast Pacific Ocean alone? Do I have the mental and physical strength to survive this fierce ocean? Has Heaven given me the power and skill to return alive to solid ground? I crawl back onto my violently rocking berth, lying there and burying my aching head under the blanket.

Suddenly, without any warning, the intense rocking stops. Curious, I glance at the cabin’s compass. Strangely, Aomi is dozens of degrees off course. I open the cabin hatch and look out to adjust the wind vane and sails.

In the next instant, the sea rises into a towering hill, foaming white before crashing over my head.

“Watch out!” I yell, hastily closing the hatch. A direct wave hits Aomi, knocking her sideways. The cabin rocks violently, and I am thrown into the air. As Aomi tilts nearly ninety degrees, the side wall swings beneath me, and I slam down hard onto it.

The next instant, however, the 880‑kilogram ballast, fixed to the bottom of the hull, acts as a counterweight and brings Aomi upright. But the cabin’s sudden swing throws me across the interior, slamming me hard into the opposite wall.

Pain shoots through my head, jaw, and chest, leaving me breathless for a while. When I manage to get up and look around, I notice that several buckets of seawater have poured in, soaking the bedding and food supplies. Cracks have formed in the wall where my head struck.

“I really let my guard down.”

The vivid white of the wave’s crest crumbles as I look up, burning itself into my memory. It feels like the blinding flash of an explosion.

Even two days after the storm passes, my head still aches and purple marks stain my chest. I suspect my ribs are broken, as each deep breath pierces with sharp pain and coughing sends a deep ache through my chest.

My mind grows increasingly restless, and I often wake in the middle of the night without knowing why.

I get up, stick my head out of the hatch, and scan the dark horizon. Bars of light flicker on the sea, thin as chopsticks or the masts of distant sailboats, then they vanish seconds later.

Hovering just above the horizon, an eerie red crescent moon casts its faint, ghostly glow.

“Mr. Moon, please, please help me.”

2. The Shining Sea

After a storm, the sea calms for a few days before the next one passes through. The weather moves in cycles. This is what summer feels like at the 38th parallel in the Pacific Ocean, where Aomi sails toward San Francisco.

Under clear sunlight, with white sails billowing in graceful curves, Aomi glides freely over the shining sea. It is a world filled with the crisp sound of breaking waves, refreshing breezes, and the quiet satisfaction of cutting through the vast ocean.

The waves breaking against the bow flash in the sunlight, sparkling like glass. The sea is so blue that a white cloth might turn into a blue handkerchief simply by dipping it into the water.

On stormy days, I become seasick and spend the entire day lying in my berth inside the tiny cabin. But once the weather clears, I feel strangely energetic. I rise quickly, as if I had only been pretending to be ill.

Every morning, when the alarm rings at 6:30 a.m., I measure the sun’s altitude with a sextant to plot Aomi’s position on a nautical chart. Then, I adjust the sail tension and hang wet clothes to dry on the railing.

I also inspect every part of Aomi and repair anything that is broken. Some days, I dry dozens of US dollar bills soaked by seawater after a storm. I heat them on the stove, much like cooking nori, Japanese seaweed.

After the evening meal and sunset, I write the voyage log under the cabin light, read some of the nautical stories on board, and then fall asleep. But even at midnight, I must rise to check the compass to stay on course.

I often spring out of my berth, when sudden rain or gusts of wind strike, and I adjust the sails if the weather turns stormy. Living at sea is like being a wild animal on the grasslands, always alert to predators. As a result, I can never sleep peacefully or deeply.

The steady rhythm of life at sea gradually breaks down, with the sky growing white as early as 2 a.m. and the sun setting by 4:30 p.m., even though it is midsummer.

I wake early to sunlight streaming into the cabin, and in the evenings, it becomes too dark to wash dishes on deck. This makes daily life inconvenient.

As Aomi sails eastward across the globe, the existence of the time difference becomes undeniable. I realize I am directly experiencing one of the proofs that the Earth is round. This is not merely knowledge from books, but something I have confirmed for myself. It is a completely different kind of knowledge from what I learned in school or through reading.

Alone in the middle of the North Pacific, I often lie on deck for hours at night, feeling the gentle breeze. I never tire of looking at the night sky.

Far away from crowded cities, the stars appear large and bright, filling me with quiet awe, as if they were ready to fall with a rushing sound. Aomi appears to float in the darkness, sailing across a galactic sea, while I lie on the deck, feeling its surface beneath my back. The sails stand like black silhouettes against the dazzling stars.

On nights with a full moon, a bluish-white light fills the air, and I can see the horizon as clearly as if it were daylight.

Under moonlight pouring down like steady rain, the sea swells in the darkness. It feels as if an enormous creature is twisting its body just beneath the surface. Aomi rushes through the fantastic moonlit sea, its hull whispering like a stream.

The moon shining over the sea is unexpectedly bright, and its intense light streaming through the window often startles me.

It shines so brightly that I sometimes leap up from my berth, thinking a ship is approaching and shining its searchlight on Aomi.

3. Approaching the New World

After eight weeks at sea, far away from the familiar common sense of the city, I have set the cabin clock six hours ahead to match the time difference.

Aomi has already crossed most of the North Pacific, over 8,000 kilometers from east to west. Clear, crisp English songs and news broadcasts now reach me on the radio. My destination, San Francisco, is finally within reach.

But a storm arises, and Aomi pitches so violently that I cannot even place the pot and kettle on the stove. I am thrown around the cabin again and again.

After dusk, I eat only canned mandarin oranges and biscuits for my first meal of the day, then return to my berth and lie there, suffering from seasickness. High waves continuously toss little Aomi from their peak to trough, the impact sending a painful shock through the hull and into my backbone. Outside, the wind roars as if threatening me in the darkness.

I estimate that Aomi is only about 100 kilometers from the American continent. If unknown currents push her, a collision with land could occur before the first light of morning.

I tell myself to go out and search for lighthouse lights, but I cannot bring myself to do it, even though I am neither hungry nor exhausted. I just lie in my berth, frozen as if in bondage, paralyzed by fear. If I went outside, a wave might strike me, and I could fall into the water, with no one to save me.

“The speed of a small sailboat is like that of a slow bicycle. The land must still be far away. I should be fine. Just go back to sleep,” I mutter.

With such excuses, Heaven would never allow me to cross the sea safely, nor would I learn anything important from the sea. With such an attitude, even if I managed to cross the Pacific Ocean, I could lose my life in the rough seas of my next destination, Cape Horn.

I feel so frustrated that I want to cry.

The next evening, after the storm subsides, Aomi and I arrive just off the coast of San Francisco. Ahead of me, the city lights and car headlights paint the night sky bright white, a striking contrast to the moon and stars I am used to seeing at sea.

A sewage-like, dirty, and rotten smell fills the air. I wonder if the sea in Japan has the same stench. Since leaving my country, I have bathed in pure white waves breaking over my head and rinsed rice with clear seawater each day. Perhaps only people who have lived at sea, far away from the human herd called “the City,” can truly recognize this stench.

Tomorrow, two months of inconvenient and painful life at sea will finally come to an end. Soon, life on land will begin, stable and free from the rocking of the waves.

But my mind is filled with anxiety. How will I survive financially in the unfamiliar land of America? How will I find a part-time job, understand what people say in English, and prepare for my next destination, the stormy Cape Horn? I feel like steering Aomi’s bow out to sea again.

America—my first foreign country!

Hi! Any questions or suggestions about the content are greatly appreciated.

I’d also love writing tips from native English speakers. Since English isn’t my first language, if you notice any awkward phrases or anything that seems off, please let me know.

Thank you!

E-mail