Japanese sailing magazine KAZI

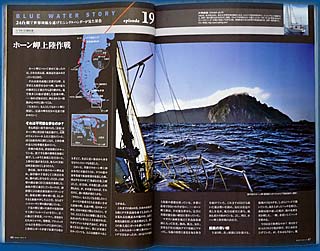

Landing on Cape Horn solo is one of the climactic moments of Aomi's voyage. Almost no precedents, information, or hope existed for a small (7.5m) single-handed sailboat like Aomi.

Let's locate Cape Horn.

Until the Panama Canal opened in 1914, ships traveling between the Atlantic and the Pacific had to sail far south and round the southernmost tip of South America.

All trade ships and battleships had to navigate through the Strait of Magellan or sail south of Cape Horn. However, the area known as the "Screaming Fifties" is notorious. Many ships wrecked there, many sailors were frightened, and many were lost. Cape Horn became a symbol of fear at sea. (One of the reasons why the wind blows stronger in the Southern Hemisphere than in the Northern Hemisphere is described in the middle of the "Exploding Waves" page.)

After the Panama Canal opened, the importance of the "Cape Horn route" diminished, and people seemed to forget the existence of the Cape at the end of the world. Only the legend of Cape Horn remained.

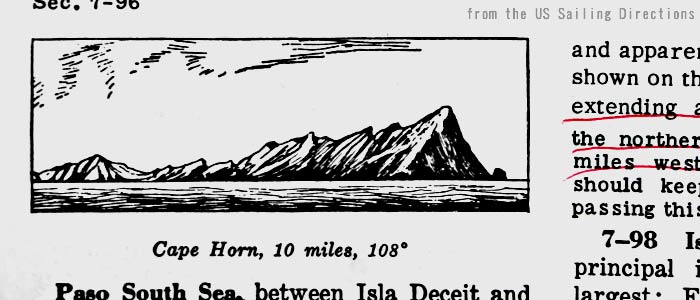

The illustration above is of Cape Horn, taken from the Sailing Directions issued by the U.S. Department of Defense.

Many years before I started my round-the-world voyage, while working for a computer company in Japan, I placed a cutout of the above drawing of Cape Horn in a plastic ticket holder and kept it in my chest pocket. Every weekday morning, as soon as I arrived at work, I took the plastic holder out of my shirt pocket and placed it on my desk. After work, I put it back in my pocket and went home. Cape Horn was always with me.

I yearned deeply for Cape Horn and hoped to go there at any cost. I wanted to see the legendary Cape with my own eyes.

However, I didn't think I would be satisfied just by seeing Cape Horn. You can see it on TV, in a photo, or even in a dream. What difference would it make?

For that reason, I had to land on Cape Horn, feel it with my own feet, and collect a small stone as proof.

But was that really possible? The idea of not only rounding the Cape of Fear but also landing on it seemed like a mere dream even to me.

*

Before arriving at Cape Horn, Aomi stopped in Punta Arenas while sailing down the Patagonian Archipelago. There, I tried to get information for the Cape Horn landing. Each time I stopped at a port, I always made significant efforts to gather information on Cape Horn.

Until the Panama Canal opened at the beginning of the 20th century, Punta Arenas flourished as a coal supply base in the Strait of Magellan. By 2002, Punta Arenas had a population of about 120,000 and was the second-largest city in the Patagonian Archipelago. It is also the only city in the 570 km-long Strait of Magellan, which connects the Atlantic and the Pacific.

In the port of Punta Arenas, I brought Aomi alongside the Chilean Naval ship Lientur to talk with the officers and correct my nautical charts. They were kind enough to give me not only information but also a free lunch, shower, engine oil, and 50 liters of fuel. (I didn't even ask for these!)

However, they had only been to Cape Horn once, and each time I asked for details, they referred to the Chilean Sailing Directions. Consequently, I couldn't get enough information from them.

Though I had Sailing Directions issued by the U.S., there was little information about Cape Horn. The Chilean Sailing Directions seemed to be more detailed.

Fortunately, I had copied some pages of the Chilean Sailing Directions when I had visited the Chilean Navy Headquarters in Valparaiso a few months earlier. Because I couldn't read Spanish, I dashed into a bookstore in Punta Arenas and bought a Spanish-English dictionary (Spanish-Japanese dictionaries were, of course, unavailable there).

Another reason for visiting Punta Arenas was to tune up Aomi's 3.5HP diesel engine for Cape Horn. I was to receive a parcel of piston rings there. The engine had issues due to the low-grade engine oil I had used.

The port of Punta Arenas was far from comfortable.

The satellite picture above shows the port of Punta Arenas. The strait is about 30 km wide at this point, with a single jetty extending into the sea. There were no breakwaters at all, making it a port with severe conditions for small boats.

The winds in the Magellan Strait are usually strong. During my stay, there were days with steep, triangular waves over 1 meter high in the port. Aomi was severely shaken and bumped against fishermen's boats at the jetty. The stainless-steel handrails of Aomi were bent, and a window broke. I had to leave the port as quickly as possible. (The severity of the wind and the scenery of the strait is described on the page of Strait of Magellan.)

*

After leaving Punta Arenas and sailing through an uninhabited area for another two weeks, Aomi arrived at the small town of Puerto Williams, a Chilean Navy base.

My target, Cape Horn, was about 150 km away. The photo below shows Puerto Williams, which I took from the Beagle Channel.

You can see antenna towers in the center, houses, and a church with triangular roofs to the left. The mountains look reddish because of the autumn colors. It was April, and winter in the Southern Hemisphere was just around the corner.

There, I gathered further information for landing on Cape Horn. What I did is described in the story Landing on Cape Horn.

*

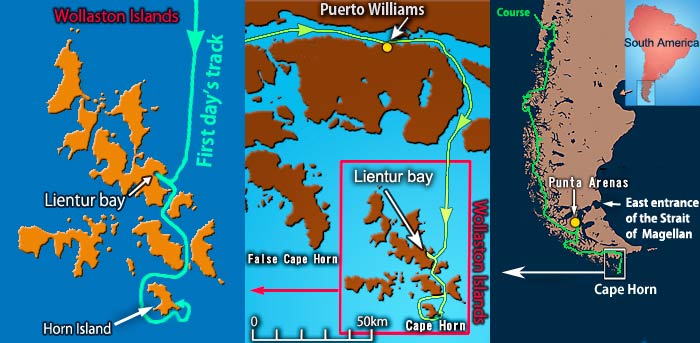

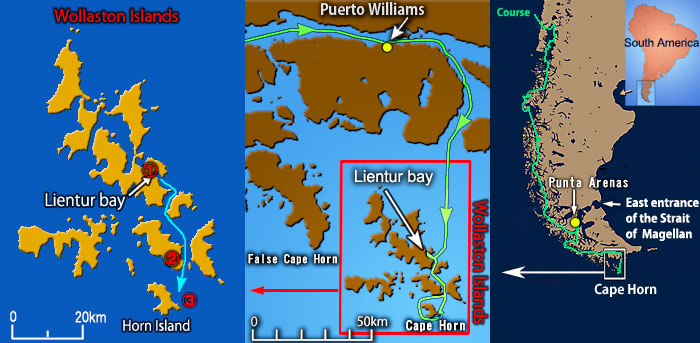

After leaving Puerto Williams, Aomi sailed south for about 130 km and entered a small bay called Lientur to wait for good weather before heading to Cape Horn. I spent two days here, waiting for favorable weather. Lientur Bay's position is indicated on the map below.

Strictly speaking, Cape Horn refers to the southernmost point of Horn Island, but it often means the entire island. It is located at the southern end of the Wollaston Islands.

The photo above was taken just after leaving Lientur Bay. The wild rocks of the islands at 55°S reflected the morning sunlight. The weather was surprisingly good, making it a truly refreshing morning.

The water between the islands was sheltered from swells, but in places, it was filled with kelp, giant seaweed that could foul Aomi's propeller. Great caution was necessary.

Although Aomi was running with sails, the engine was ready and idling in case of emergency. Strong gusts of wind sometimes blew and heeled Aomi considerably.

The above photo shows a view from the northwest end of Horn Island. In the center-right of the photo, you can see the island's summit in the distance. The Comandante in Puerto Williams advised me that the water around this point was unsurveyed and required great caution. Paying close attention, Aomi continued to sail ahead.

I took this photo from west of Horn Island. There was only a light wind, but some swells of the open sea. The Cape I had longed for looked like a huge animal to me.

By the way, what is the fine weather like today? Is this really the Cape of Fear?

Aomi approached the southwest of Cape Horn. The Cape rose from the water, displaying its wild, rocky, dignified, and dreadful appearance. Paying close attention to uncharted rocks, Aomi sailed as close as possible to the Cape, searching for a suitable landing spot.

Despite the risk of hitting rocks by sailing closer to the coast, I needed to find a suitable landing place. I took the photo from the south, in front of the Cape, where the mountain—406 meters high according to Chilean charts but 424 meters in the U.S. Sailing Directions at that time—stood silhouetted against the sunlight. Alternating my gaze between the water ahead and the depth sounder, I carefully navigated Aomi.

Soon, the first possible landing site appeared on the coast. It was a small bay with numerous round rocks that looked like human heads on the beach, and waves were breaking violently. Rowing a dinghy seemed impossible, so I gave up on this bay.

After rounding dangerous rocks at the island's southeast corner, Aomi sailed to the east side of the Cape. Then, the second possible site appeared.

I checked the seafloor with the depth sounder, lowered an anchor, and tested its effectiveness, but the anchor slipped. Eventually, I was unable to land and had to dash back to Lientur Bay while the wind picked up. The storm of Cape Horn had returned, and the day's fine weather seemed like just a dream.

*

When landing on Cape Horn, the most crucial consideration is preparation for a sudden storm. If a strong wind began to blow, getting back to Aomi with a small rowing boat might be impossible. Furthermore, if the wind became much stronger, Aomi could be blown away unmanned. Perfect anchoring was essential to prevent accidents.

To prepare for that, I dropped anchors in many bays. I brushed up my skills while sailing down the Patagonian Archipelago for over four months.

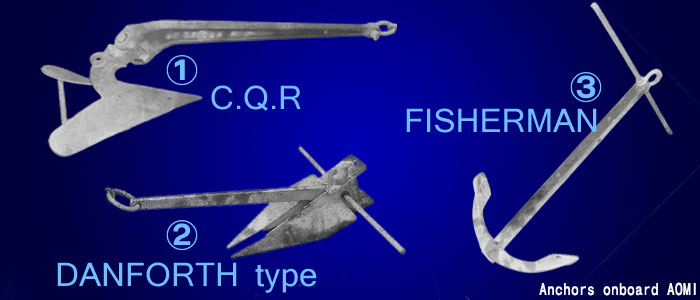

The anchors shown above were onboard Aomi. Why are so many types of anchors necessary? Isn't one anchor enough?

You have to select anchors based on the seafloor.

① is a CQR anchor, suitable for mud but not for rocky seafloors.

② is a Danforth-style anchor, said to be good for sand but not for rocky seafloors.

③ is a Fisherman anchor, relatively good for the bottom of rock or seaweed, but has less holding power due to its small flukes.

You have to check the type of seafloor and select the best anchor.

Furthermore, you need to check the shape of the seafloor with the depth sounder before anchoring. But why?

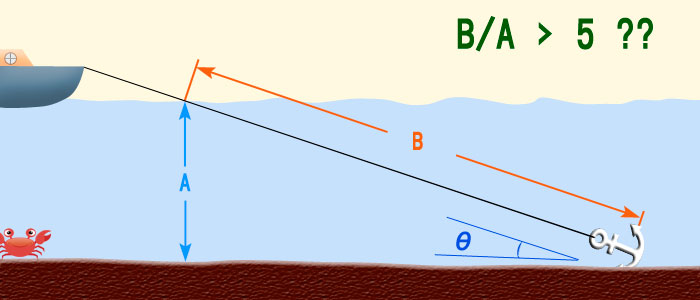

The above figure shows the general method of anchoring. The length of the anchor rope should be at least three to five times the depth. If the angle (θ) between the rope and the seafloor is too large, pulling the rope forcefully may cause the anchor to come loose. Therefore, a longer rope is recommended, which makes the angle smaller.

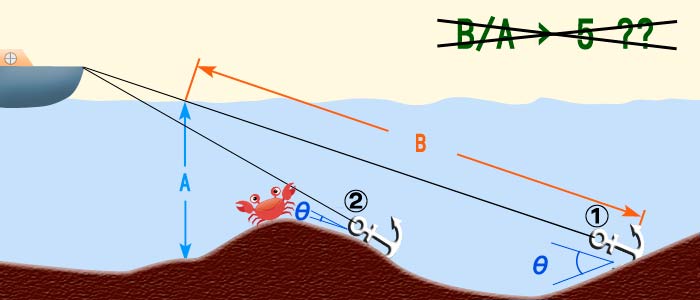

That is the description of the proper anchoring in most textbooks, but it isn't always true.

The reason is that seafloors are not always flat. In the figure above, rope ① is longer than rope ②. So, does ① look better than ②? Consider the angle between the ropes and the seafloor. The angle of rope ① is much larger than that of rope ②. This means the anchor for rope ① will easily come out of the seafloor when the rope is pulled. In contrast, rope ② is shorter but nearly parallel to the seafloor, allowing the anchor to hold the seafloor securely.

That's why you must check the shape of the seafloor before anchoring. Also, be cautious of any submerged objects, such as wrecks, trees, and other ships' anchors to avoid fouling your anchor.

*

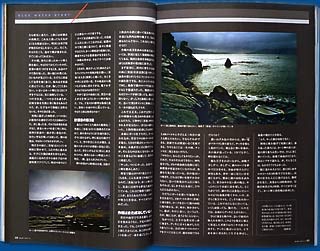

Though I was unable to land on Cape Horn that day, I made Aomi run in the bay lengthwise and breadthwise to check the seafloor with a depth sounder and create a map of the bay. After that, Aomi returned to Lientur Bay to wait for good weather before attempting to land again.

The photo below shows Aomi anchored in Lientur Bay, awaiting good weather.

The small bay was surrounded by mountains and protected from the storm. The tops of the mountains were covered with snow. There was a lake between the nearby hill and the distant mountains. Water from the lake flowed down into the bay, creating a waterfall (center left in the photo). I felt a desire to walk on land.

A few days later, as the storm subsided, Aomi left Lientur Bay (indicated by the symbol "①" on the map below) and headed for Horn Island. After sailing between islands for about two hours, Aomi arrived at point ②, where Horn Island appeared ahead. After another hour of sailing, Aomi reached the targeted bay for landing (③).

This is a view from point ②. Aomi entered the open sea after navigating between islands.

You can see the summit of Cape Horn in the center of the photo above. It was lit by a spotlight of sunlight shining through a small hole in the clouds. It was a breathtaking moment.

This is a view from point ③, the landing site. There was just a light wind and small waves in the bay because the Cape itself blocked them. That was exactly what I expected. The reason I chose that day for the landing was, indeed, the favorable wind direction.

On the right-hand side of the photo above, Aomi's mast is leaning, and the water looks whitish. There must have been a lot of wind off the coast. Aomi's engine was running in case of an emergency, though nobody was on board. On the rocky beach, you can see a plastic folding boat for landing.

In the center of the satellite photo above, you can see two small bays close to each other, forming a shape that looks like a "w." The one on the right is the landing place. I recently identified the exact location after seeing the satellite picture, as there hadn't been enough information on the charts, and the shape of the land had been uncertain.

After one hour on land, Aomi left the bay. The water in the bay was partially covered with kelp (giant seaweed), as seen in the photo. I had to pay close attention to the propeller.

Then, the wind gained force, and hail began to fall from the dark, leaden sky. Aomi had to dash back into Lientur Bay. The storm of Cape Horn had returned.

* To learn more, read the story, Landing on Cape Horn.

Back to main page.