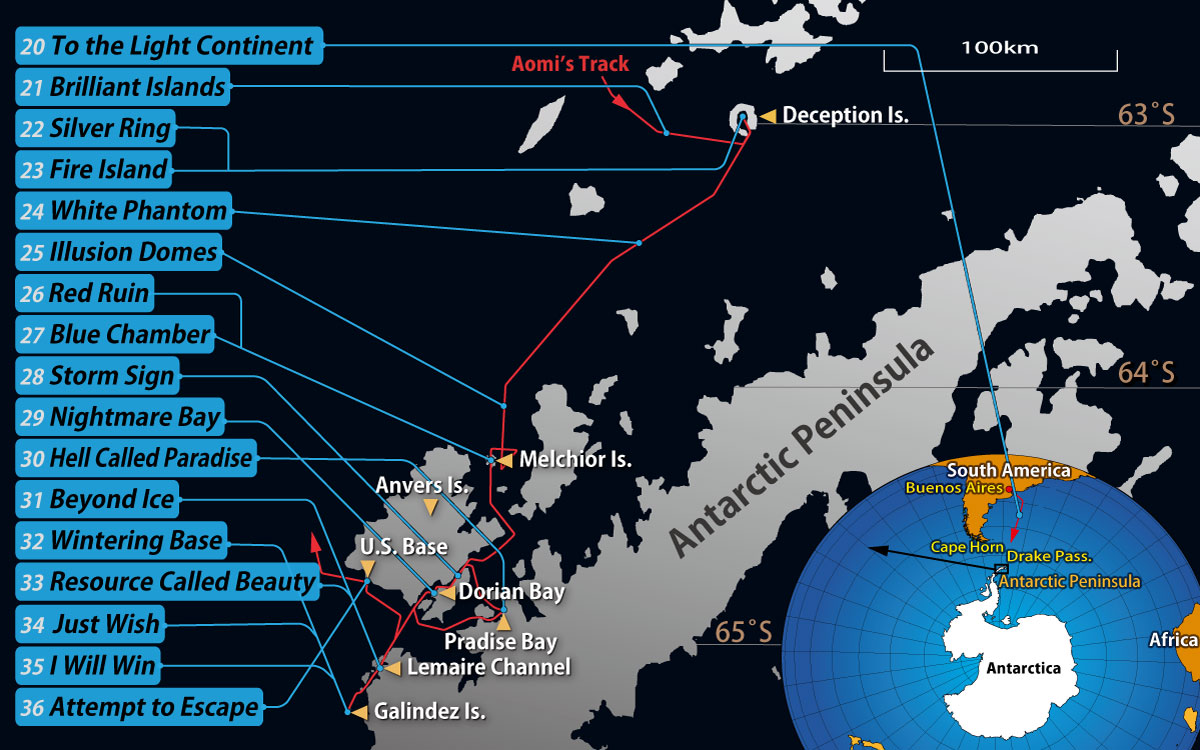

20. To the Light Continent

1. Days of Hope

It was certain. There was no doubt in my mind.

Antarctica, the southernmost continent on Earth, is twice the size of Australia and covered in thick ice averaging more than 2,000 meters. It remains a frontier dominated by the unknown and the ice.

The crystal-clear air, pure white icebergs floating in the dark blue sea, and a world filled with seals and penguins.

After completing my voyage through the Patagonian Archipelago, I could easily imagine how spectacular the Antarctic Peninsula must be, sharing the same geological origins as Patagonia.

In the surrounding sea, islands rise more than 1,000 meters above sea level, covered in ice and shining with a dazzling silvery white. It must be the most beautiful place on Earth. There was no doubt about it.

I longed to go there.

I wanted to sail to this land of light at any cost.

A passion for the journey, which I had never imagined before, was rising uncontrollably within me. But could I really sail alone to Antarctica in Aomi, a sailboat only 7.5 meters long?

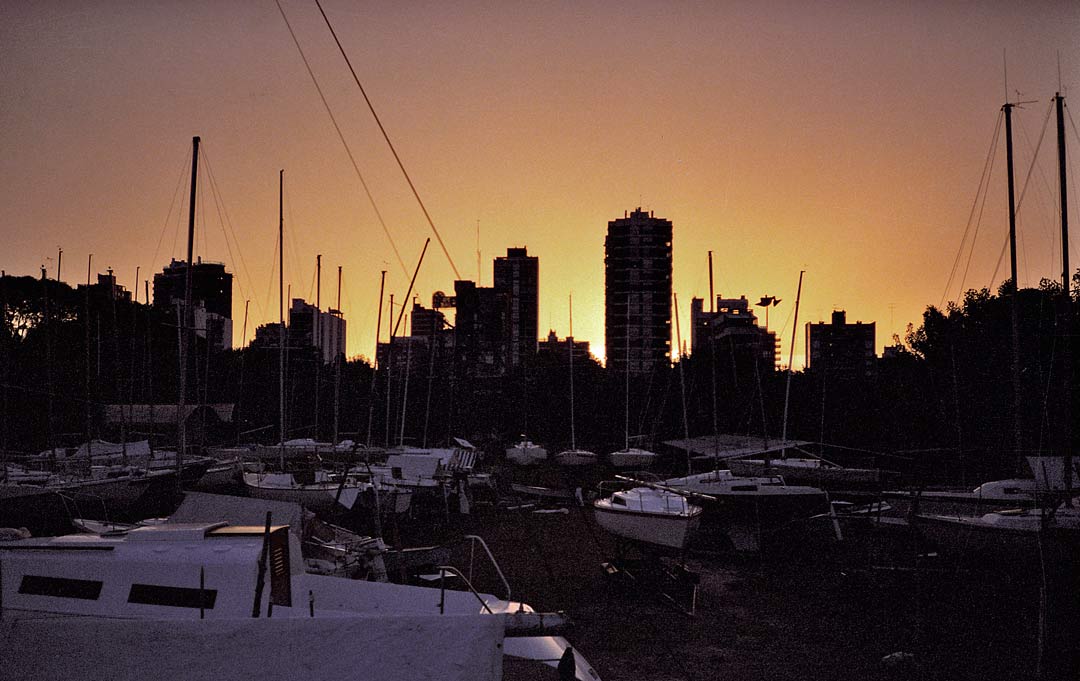

After nearly two years away from Japan, rounding Cape Horn, and entering the South Atlantic, I arrived in Buenos Aires, the capital of Argentina. I spent my days in deep contemplation.

“On a solo voyage, you will hit an iceberg while sleeping.”

“If you sail in a small boat and get surrounded by drift ice, you will not be able to move.”

“If it is not an iron ship, countless floating ice blocks will scrape it, opening holes in the hull and causing it to sink.”

“The Drake Passage, between South America and Antarctica, is the roughest sea on Earth.”

At the suburban yacht club, all the members said the same thing. They tried to persuade me to give up my reckless adventure and cherish my life.

Of course, I knew it was dangerous. But I was far from home, in the capital of Argentina, close to Antarctica. Aomi, my means to get there, was also here. If I missed this opportunity, I might never have another chance to go.

If I prepare carefully, try, and continue my efforts and ingenuity without giving up, I will surely succeed, just as I did when I landed on Cape Horn.

In Buenos Aires, a city of three million known as the Paris of South America, I stayed in Aomi at a yacht club and walked the old European-style streets to gather information. Riding Mercedes-Benz buses on streets laid out like a chessboard, I visited the Argentine National Antarctic Office (Dirección Nacional del Antártico), the National Library, and the Chilean Embassy to collect materials on Antarctica.

The more I learned about the cold sea, the more my anxiety and worry grew. Sailing alone made it difficult to keep watch constantly. If the sailboat collided with an iceberg in the Drake Passage, Aomi would sink to a depth of 4,000 meters.

Even if I were lucky enough to reach Antarctica, the bottom of Aomi could be scraped away, and holes might open from navigating through floating ice. Aomi could also be crushed between the land and moving icebergs.

Yet if I solve these problems one by one, I can surely realize my dream.

Buenos Aires is a city where the La Plata River, several dozen kilometers wide, glistens like a sheet of silver. About six months after arriving, I ran out of money. Even in the midsummer heat, when I was thirsty, I could not afford a drink. I wore torn clothes and shoes picked up from garbage cans, and sometimes I was given leftover bread and meat as if I were a street person.

The kind people at the yacht club invited me to lunch several times. We drank local wine from noon, and everyone said,

“Even though prices rise ten times a year, this country is where people care for their friends. When we are in trouble, we take care of each other. Unlike paper money, which quickly loses its value, friends are precious treasures.”

Living on $20 a month was not hard when I thought of my dream of sailing to Antarctica. However, modifying Aomi for the icy seas would require several thousand dollars in materials. Even if I tried to earn money, the average monthly income in this country was about $100, and with the high unemployment rate, finding a suitable job was nearly impossible.

At a loss, I considered becoming a private tutor. There were dozens of Japanese businesses and embassy families in Buenos Aires. They must have worried about their children’s education because there were no cram schools or prep schools like in Japan. When I visited the Japanese school in the suburbs and talked to the teachers, I was fortunate to find four students.

I worked at night to earn money. During the day, I continued modifying Aomi, spoiling my work clothes with paint and glue. Although it initially seemed hopeless, I found ways to make her safer from floating ice.

I installed a large truck rearview mirror on the hatch to watch icebergs while lying in the cabin berth. I attached small steps to the mast to climb up and down to monitor the ice from a higher position. To prepare for collisions with floating ice, I built watertight bulkheads inside the hull. I also covered her bottom with stainless plates, stainless mesh, and reinforced plastic, which took several months to complete. Additionally, I lined the cabin’s walls and ceiling with Styrofoam to protect against the cold and, as always, gave the engine a thorough overhaul.

Modifying a sailboat while taking buses and trains for materials in a foreign country with different languages and customs was an enormous task for me alone. It was not until the end of February that I completed my preparations for departure—already my second Christmas and New Year in Buenos Aires.

I would arrive in Antarctica, 3,000 kilometers to the south, at the beginning of April. It was out of season and certainly against all common sense. I knew, of course, that the icy waters welcomed sailboats only between December and February, the height of summer in the Southern Hemisphere.

Still, I will try to challenge what I have already decided. If there is too much ice and danger, I’ll turn back at once. I believe I will be lucky and succeed, just as when I landed on Cape Horn.

Now, I’ll set sail for the southernmost continent and sea on Earth.

Aomi set two sails on the mast, one fore and one aft. After two days of sailing, she left the muddy brown La Plata River and entered the open sea for the first time in a year and a half. The sea around her was as blue as ever but somehow different.

I tried to imagine myself arriving in Antarctica.

Looking up at the majestic, shining mountains of ice, I might feel emotions rising and freeze in wonder. I might even shake hands with penguins.

I closed my eyes and tried to focus, but all I saw was a terrible, terrifying darkness.

A few days after departure, I noticed a small, unfinished spider web on the corner of the deck railing. A spider, the size of a grain of rice, frantically ran around on the violently rocking web, trying to finish it. Did the spider know there was no prey on the sea and that Aomi was heading for Antarctica, a place too cold for such a tiny creature to survive?

A single gust of wind, a single crash of a wave, and the spider’s life would be over. So why do you keep struggling for nothing, almost swept away from your violently rocking web?

The next day, the spider and its web were gone.

“A small life can easily perish in the fickleness of the wind and waves,”

I muttered to myself over and over.

Find more details on the Antarctic Challenge page.

2. Distress

This might be the most foolish tale.

The sky is clear and blue, with almost no clouds in sight. But on the horizon, a dark cloud has gathered in one spot, swirling ominously. Aomi heads straight for the dark mass, as if drawn to it.

Have I let my guard down? The barometer reading is not low, and the sun is still shining. It’s just a small low-pressure system, anyway.

Soon, the roar of the wind increases, and black clouds blanket the sky. Aomi races through the evening sea, her sails billowing in the strong following wind. I am happy to gain speed, but the wind grows stronger and stronger, threatening to tear the sails away at any moment.

Worried, I pull the mainsail down from the mast. Suddenly, the sun sets, and darkness envelops the sea.

Lightning occasionally illuminates the night sky far from civilization, casting an ominous glow over black clouds on the horizon. The eerie spectacle suits the South Atlantic Ocean, stretching to the ends of the earth. It would not be surprising if mythical monsters suddenly emerged from the vast expanse of the sea.

The waves on the black sea rise rapidly with the increasing strength of the following wind, howling across the dark sky like a demon’s voice.

Eventually, the waves collapse as if rolling their heads in, covering Aomi one after another. Hoping and praying the sea will not get any rougher, I open the hatch, go down to the cabin, take off my oilskin and boots, and lie down on the violently rocking berth.

Shortly after midnight, a sound like the shattering of a huge glass object echoes through the absolute darkness. At the same time, a wave’s impact violently throws me into the air.

“Capsized? Tipped over? But what was that tremendous sound?” My mind races.

Feeling for the switchboard with my hand, I turn on the cabin light, regain my sense of up and down, and immediately understand what has happened.

Aomi, having capsized in heavy seas, is brought back upright by the ballast attached to her bottom. But with the strong wind in the sails, the hull, once running like an arrow, loses all speed and now simply rocks with the waves.

That means… This should never have happened.

I hastily grab a flashlight, open the hatch, and shine the light overhead. All I see are splashing waves and the howling gale, filling the darkness.

“It’s gone. The mast is gone. It finally broke.”

What should never have happened has occurred. The dream of reaching Antarctica, the voyage of Aomi—everything is over. Everything is ruined. All the strength drains from my body.

Aomi’s hull is continuously rocked by heavy waves, and I hear dull sounds and feel impacts I have never felt before. Something keeps hitting the hull, again and again.

When I turn my flashlight toward the water, I see something long, like a pillar, sticking out of the sea, with long silvery whiskers or ivy tangled around it. The strange object, which I cannot tell if it is an animal or a plant, bangs against Aomi’s side with the motion of the waves. I have never seen anything like this before.

It is the broken aluminum mast, with support wires attached, submerged upside down in the sea.

That’s enough. I can’t do it anymore.

I go back to my cabin and bury my head in the blanket. I spent a year and a half in Buenos Aires, putting all my effort and ingenuity into preparing for Antarctica…

The hull, rocked by heavy waves, echoes with one dull bang after another. If I do not retrieve the mast immediately, Aomi’s 5‑millimeter-thick hull will break, and she will sink. Reluctantly, I put on my oilskin, grab a flashlight, and step out into the pitch-black darkness, with waves crashing around me.

In the cone of light, the broken edge of the mast—an aluminum pipe sticking out from the sea—is as sharp as a blade, moving with the waves like a living creature. A careless touch could slice off a finger or two in an instant.

Though my Aomi is severely wounded, I am still in one piece. I have to begin the recovery work carefully, ensuring I do not injure myself.

But the pipe of Aomi’s mast, 13 centimeters in diameter and weighing between 20 and 30 kilograms in air, would be about five times as heavy when filled with water. Can I, just one person, pull it out in this storm and darkness, on the deck rocking as if to throw me off? Can I do it without delay before it breaks through Aomi’s hull?

No, it is impossible. Even if I could, a wave would throw me overboard, and the strong wind would immediately separate me from Aomi.

It feels as painful as losing a part of my body, but I have to unscrew the wires connecting the mast to the hull and let the mast sink into the sea. There is no other way to save Aomi.

With a headlamp on my forehead and a lifeline about 1 meter long tied to my chest, I crawl along the deck, changing the lifeline hook on the railing as I go. The storm roars like a scream, and the deck rocks up and down several meters in the darkness, whose depth and width are immeasurable.

For tiny Aomi, the deep black sea feels infinite. The deck, illuminated by my headlamp, is just about 2 meters wide, the only place I can survive.

However, waves crashing over my head, one after another, try to wash me away from this narrow reality into an unknowable darkness. If I lose my grip on the railing while changing the lifeline’s hook, I will fall instantly into a darkness that may last forever.

Pulling a pair of pliers from my oilskin pocket, I remove the ends of the wires attached to the front, back, left, and right of the hull, one by one, as waves splash over me.

Of the seven wires, I leave the one at the bow. The mast will hang in the water from the bow and act as resistance, keeping the bow facing the waves directly. That would reduce the impact of the waves on the hull.

After finishing the task, I crawl back to the cabin across the violently rocking deck. Clothes, books, and food have flown off the shelves during the capsize, filling the cabin floor up to my knees. It looks like a great earthquake hit.

Every time a heavy wave approaches with an eerie rumbling sound, though sometimes in silence, it strikes little Aomi with a powerful crash, and the cabin tilts more than 60 degrees. Knives, forks, and broken glass bottles fly through the air, along with my body.

I have been hit all over my body, and the seasickness is severe. My head spins as if I am wearing glasses made from the bottoms of bottles. Fighting the nausea, I crawl into the berth and pull the blanket over my head. My face is slick with blood, but I do not have the energy to bandage it.

Find more details on the Exploding Waves page.

3. Hope Shattered

Morning arrives.

I must have slept on the seawater-soaked berth for about four hours. Outside the window, the sun shines brightly in an unexpectedly clear sky, and the wind whistles through the air.

Last night’s capsize must have been a dream, just a bad dream. It cannot be real. Aomi’s mast is thoroughly inspected and maintained, with none of the supporting wires cut, so it should not have broken.

With a prayerful heart, I open the hatch and look out.

Strangely, the white sails that always billow in the wind and fill half the sky, the nine-meter mast towering above me, and its 7 support wires stretching overhead from masthead to deck are all gone. That familiar sight has vanished, as if the ceilings and walls of my long-time home had been stripped away, leaving me looking up at the sky from the floor.

When I lower my eyes to the water around me, I see a strange, hair-raising silvery world.

Snow—snow seems piled on top of the waves rising and falling alternately.

The water bubbles created by the strong wind look like pure white snow. It feels like being in an aircraft, wandering above winter mountains.

How will I return to land? Aomi’s small engine is only for entering and leaving harbors; it cannot make progress in rough seas.

Without her mast and unable to set sail, Aomi is like a bird that has lost its wings. She could be carried by the currents, circling the seas forever, until food runs out. Even if I were lucky enough to catch some fish… what about water? Drinking water?

Aomi’s sliding hatch is tightly locked from the inside. Once the entrance, vents, water supply, and drain holes are closed, the sailboat becomes a capsule floating between the waves. There is no danger of sinking, even if the boat turns upside down. No matter how big the waves grow, there is nothing to fear.

This feeling of safety quickly fades as the waves grow stronger. The waves striking Aomi feel solid, like a steel container fallen from a cargo ship, a large piece of driftwood, or even a whale. Each blow echoes painfully through my body, the powerful sound ringing in my ears. It feels as if I am being slammed hard and repeatedly into the ground. How long can my body endure this?

Every time huge waves crash against the hull, I hear a creaking sound like snapping wood. If I do nothing, the thin reinforced-plastic hull will break, and Aomi will sink.

The mast wreckage, hanging from the bow into the sea, seems ineffective as drag. So I decide to cut off the useless mast and set a parachute-type sea anchor instead. Aomi’s bow will turn toward the waves due to the sea anchor’s resistance, limiting the impact by exposing the smallest surface area to the waves.

Putting on my oilskin and boots, I open the sliding hatch and run onto the deck, where the wind is howling.

A few seconds later, the sea surface rises like a hill beside Aomi. A white, foaming mass collapses from above, throwing me toward the sea.

I’m going to fall in. I’ve finally been hit. I can’t survive this. But wait, just wait, I have to grab something quickly—A rush of thoughts floods my mind.

When I regain consciousness, sharp pain shoots through my head, chest, and lower back from the impact. Fortunately, my body has stopped at the edge of the deck, but the lifeline on my chest has come free from the deck fitting.

With all my strength, I lift my aching body and crawl across the wet, slippery deck. Nearly swept overboard several times, I manage to pull out the pin at the end of the wire connecting the mast to the bow.

The mast, always inspected and maintained, as precious as part of my own body, sinks to the bottom with its sails and wires still attached.

What a waste. I have no choice but to do this to protect Aomi and return alive.

I take the sea anchor from its cloth bag, quickly tie a rope, and throw it into the raging sea. In the foaming white water of the storm, like a winter mountain range, the orange parachute sea anchor stands out with eerie vividness.

After finishing the work, I finally return to the cabin and collapse on the violently rocking berth. My mind and body are entirely exhausted, and an unbearable sadness washes over me.

Breaking a mast is something a careless fool or a novice would do—I used to think so. But now, I realize I am one of those fools. After successfully landing on Cape Horn, I thought I knew everything about sailing and the sea. I believed I had acquired the skills and knowledge to travel freely on this blue water planet called Earth. Yet in truth, I knew nothing.

I left my birthplace, spent years in fruitless effort and hard work, wasted the days of youth that will never return, and ultimately learned nothing.

Though I thought I understood the sea’s fear and harshness in my mind, I had not felt them in my body—my physical body. Frustration overwhelms me until I want to cry.

Picking up pots and dishes from the piles of books and clothes scattered across the floor, I finally find a lighter and light the kerosene burner to heat some canned soup I had carefully saved. No matter how seasick I was, this soup always tasted good. But now it is strangely tasteless, as if my nerves have gone numb from despair and extreme fatigue.

Why do I sail at sea, when life on land is so much more comfortable, safer, and easier? How will this voyage help anyone? Will it even help me? And yet, do I continue only because I once resolved to?

If I am lucky enough to reach land, I will find a way to earn money for the trip and return home immediately by plane. Although I once thought of sharing my fate with Aomi, I do not want to die at sea in such pain, hardship, seasickness, and despair. Even if I must leave Aomi behind, I want to survive and return to my country as soon as possible. I miss the soba noodles at the stand-up stall in the train station.

I cannot help feeling sorry for Aomi. She is truly irreplaceable to me, and I have faced life and death with her. Though she was created in this world without asking for it, she will be abandoned after traveling 25,000 kilometers. Perhaps she wished for neither. But maybe this sadness applies to all things, whether created or born.

Two days after the capsize, the storm subsides, and the horizon reappears behind the waves. I begin preparing a temporary mast: a long pole, a small sail, wire and wire clips, and a pulley with a stopper. All of these had been made ready at the time of departure, just in case.

After completing the short emergency mast, about two meters long, I hoist sails so small that I doubt their usefulness, and let the wind fill them.

Even if Aomi could sail in a straight line, did not capsize again, was not swept away by any current, and faced no headwinds at all, it is still 500 kilometers to the nearest land.

“Defeated,” I murmur into the orange glow of the sunset as I steer.

For more details, see the No Mast page.

4. Never More

A week after the capsize, Aomi, having lost her mast, finally reached land.

In Mar del Plata, Argentina, a tourist town known for its immense 20,000-seat casino, Aomi quietly docked at a yacht club pier in a corner of the harbor.

“What a relief. I’m saved. I’m alive. I’m finally on land!”

I was so happy, skipping down the street, but the feeling lasted only a few days.

For the past year and a half, I had walked around Buenos Aires seeking information about Antarctica, worked part-time jobs to earn money, and reduced my living expenses to as little as $20 a month. I also modified Aomi, covered in sweat, paint, and glue. Yet, I had never thought it would end up like this.

Since leaving my country three and a half years earlier, I had faced many dangers at sea. But each time I overcame them, the bitter memories and the painful memories were replaced by courage and confidence for the next voyage. Despite my fear of the sea, I had never considered giving up.

Feeling defeated, I lay down in Aomi’s cabin, enduring the pain of a broken dream for a month after I arrived.

Carrots, tomatoes, and onions, along with books, clothes, and dishes, were scattered on the tiny cabin floor and had begun to rot. Rice grains spilled during the capsize had stuck to Aomi’s low ceiling with seawater and occasionally fell off.

The faint sound of falling rice startled me awake several times a night. The shock of the capsize left me in an unusually heightened emotional state.

Every day, curious people who had heard the rumors visited the pier, pointing at the mastless Aomi and whispering.

But no one offered words of sympathy or encouragement. I sent letters of sorrow to my friends in Japan but received no reply.

Does no one take losers seriously? Have they forgotten about me? Is risking my life on this voyage, my dream of reaching Antarctica, meaningless?

I had lost all my courage in the capsize. The fear of the sea pierced my heart like a knife. Once brave, once fearless, I had become a coward.

Each time I saw a wave crash on the shore, memories of the white sea, like winter mountains, came back to me, and the roar of the sea echoing in the harbor at night pierced deep into my chest.

Jean Yve Reymond was a tall, twenty-three-year-old Swiss man I met at the harbor.

He had left the Mediterranean in a self-built wooden sailboat, headed for South America, crossed the Atlantic alone, and arrived in Argentina. From there he planned to continue south to the Strait of Magellan. Jean’s sailboat, Farewell, was 7.5 meters long, the same size as Aomi.

Everyone in the harbor warned him that sailing south in a small boat through the stormy South Atlantic in winter was reckless and suicidal. Yet he did not listen.

“What’s really important is courage and a strong will. The size of the boat doesn’t matter, and neither does the size of the storm,” he said confidently.

I gave him sixty cans of food and copies of charts. Then I encouraged him as I watched Farewell leave the port.

“Hang in there. Never give up, and never forget your courage and strong will.”

Two weeks later, just before entering the Strait of Magellan, Farewell was reportedly struck by a massive wave around 51 degrees south latitude. The wave damaged her hull, and she sank.

Before I left my country, I confidently told my friends, “Even if I lose the mast in a storm and drift to a deserted island, I’ll cut down trees, build a new mast, and continue my voyage without giving up.”

A Frenchman in his mid-forties arrived at the harbor aboard a large sailboat. He had been the captain of Calypso, a vessel once used by the ocean explorer Jacques-Yves Cousteau.

He had dreamed of going to Antarctica for twenty years, saved money, built a steel sailboat named Ksar, and finally visited the Antarctic Peninsula that summer with his crew and a cat.

He warned me firmly in his perfectly equipped cabin, which featured a gas stove, hot water shower, and expensive electronic navigation equipment.

“You should not go to Antarctica in such a small boat. The Drake Passage, separating South America from Antarctica, is the most dangerous sea in the world.”

He took a book from the shelf, opened it, and showed me a photograph of a massive wave. It was incredibly high, with its crest curling and collapsing.

“It is fifteen meters high. That is no guess: a scientifically measured and reliable figure. We encounter waves this high in the Drake Passage. Your boat’s mast is probably half that height. What will you do when a wave like this hits?”

He continued in a serious tone.

“We were so relieved when we finally reached Cape Horn after leaving Antarctica and crossing the Drake Passage. Even Cape Horn, famous for its storms, feels peaceful once you have endured the Drake Passage.”

I had no response.

“In the past, a man set out for Antarctica in an ill-equipped sailboat. It capsized on the way, lost its mast, and he asked a U.S. Antarctic base for help. Since then, people at the bases have considered sailboats an inconvenience. But the number of well-equipped sailboats has increased in recent years, and we are now welcomed. If you go there and have an accident, they will close their doors again. They may refuse sailboats in the future.”

He even added, in fact, “I do not care if a small sailboat sinks or you die. I just cannot bear to lose the pleasure of sailing to Antarctica.”

“Even if you successfully cross the Drake Passage and reach the coast of Antarctica, your boat will be scraped by countless ice floes, inevitably causing holes in the hull. A voyage to Antarctica is only possible with a steel ship like mine. Sailing in a small boat made of reinforced plastic, and doing it alone without someone to watch for icebergs in turns, would be suicide.”

He said this decisively.

5. Rise Again!

–But he was wrong. Completely mistaken.

He knew nothing about Aomi. I had installed a large truck mirror to monitor icebergs from my berth, covered the bow with metal plates to protect against ice collisions, and reinforced the hull with “ice beams”

and waterproof partitions. I also covered the front half of Aomi’s hull with stainless steel mesh to guard against ice scraping.

I can do this—with Aomi.

I will reach Antarctica, no matter the cost.

I must go, no matter what it takes. This is my decision, and I will not accept any excuses.

If I abandon my dreams halfway because it is hard, painful, or frightening, then what was the point of all my effort, all the years of hard work, and all those youthful days that will never return?

One of my goals before leaving my country was to cultivate mental strength and fortitude through this voyage. But if I give up now, if I abandon my journey, the four years since I left would be meaningless. No, worse than meaningless.

Now is the time to stand up. Now is the time of trial. Is it not youth that rises again after a fall?

A solo voyage to Antarctica is full of uncertainty and danger. There is no record of a sailboat as small as Aomi reaching the Antarctic continent. I am unsure if it is even possible. Still, I will do everything to make my dream come true: build a stronger mast, carefully maintain the hull, and strengthen both my body and mind.

I will not give up. I will persist with determination, effort, and ingenuity. No matter the challenges, I will overcome them, just as I did when I landed on Cape Horn.

I continued my daily runs to the harbor breakwater and stood before the night sea. I stared at the South Atlantic’s crumbling waves, but fear no longer held me.

After scheduling my next attempt for six months later, the following summer, I loaded Aomi onto a trailer and left Mar del Plata, driving across the Argentine grasslands from dawn until dusk. As the orange sun sank into the flat landscape like a disk, it felt as if I were watching a dazzling sunset over the nostalgic open sea horizon.

As soon as I arrived back in Buenos Aires, 400 kilometers to the north, I began working to earn money while living aboard Aomi, which was moored at the yacht club. Each night, I visited the homes of junior high students in a wealthy residential area, teaching them mathematics and science each evening for four hours.

During the day, I continued repairs on Aomi. To build a stronger mast, I studied strength calculations and conducted destructive strength tests on a sample mast at an industrial testing laboratory.

I also needed new stainless steel fittings for the mast, so I designed them on Aomi’s chart table and spent weeks at a friend’s machine shop, using the machining and welding equipment to fabricate them myself.

Racing against time, I took buses and trains across the city to industrial hardware stores and friends’ factories, or I worked on Aomi’s engine, often forgetting to eat.

The months of repairs and tutoring slipped away like days in a dream. Then, summer returned to Buenos Aires.

With a sturdy, double-structured mast rising on deck and several months’ supply of food and water loaded, Aomi was finally ready to depart by the end of January. But once again, I was well past the scheduled departure date.

Somehow, I have to make it in time for the end of the Antarctic summer.

After leaving Buenos Aires, Aomi sailed steadily southward for one week, then another.

The latitude shifted from 35 to 40, then to 50 degrees. The temperature dropped from 15 to below 10. The air pressure steadily fell, and the waves increased in height and force.

Aomi’s violent rocking sent dishes and books flying around the cramped cabin, and neither of the seasickness medications I brought worked.

Even lying in my berth, I felt intense pain. I pulled the blanket over my head, enduring the pounding of the waves against my spine and the threatening howl of the wind.

I knew it was getting harder; I knew I was starving, but I did not have the energy to cook. Instead of heading south, I felt as if I were falling headfirst into the unknown hell called Antarctica.

Why am I going to Antarctica? Can I really reach the world’s southernmost sea and continent? Even if I could reach the Antarctic Sea, could I sail safely through the ice? Could I return safely? No—such thoughts do not matter.

Is it a success if I return home alive, and a failure if I lose my life? Is success good, and failure bad?

Hi! Any questions or suggestions about the content are greatly appreciated.

I’d also love writing tips from native English speakers. Since English isn’t my first language, if you notice any awkward phrases or anything that seems off, please let me know.

Thank you!

E-mail