29. Nightmare Bay

1. Encounter

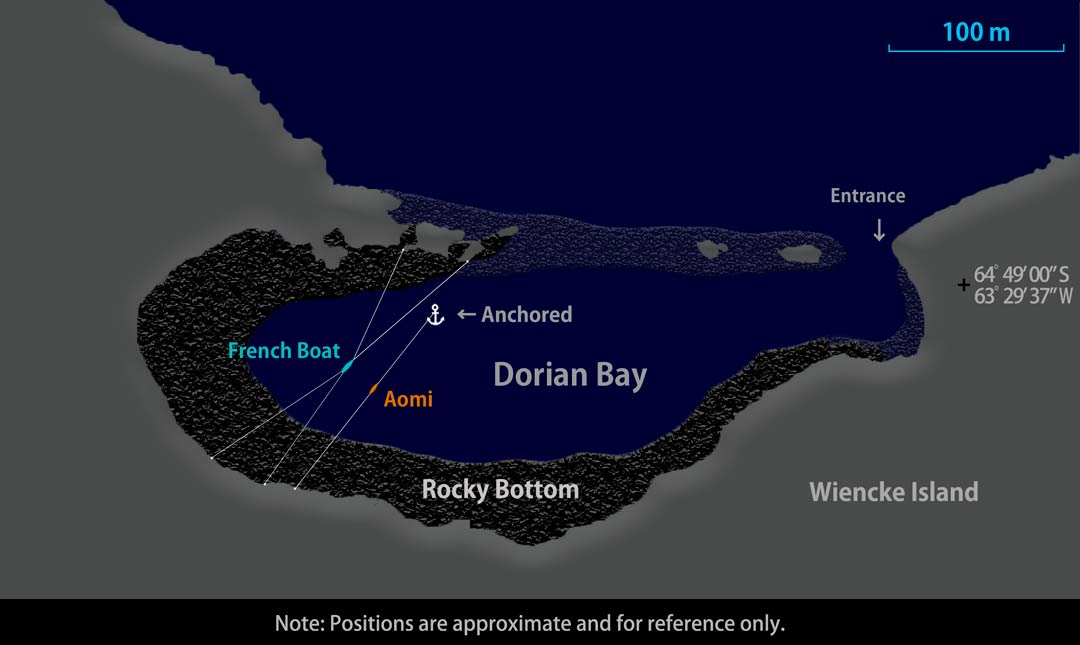

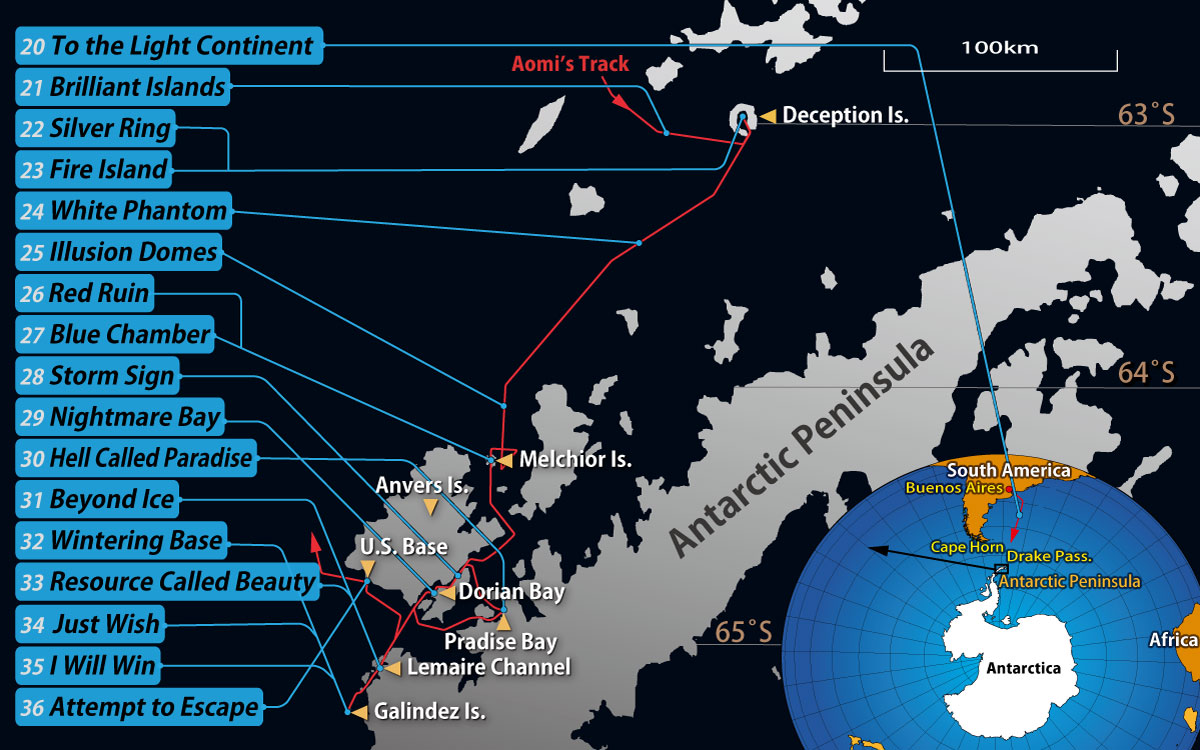

Surprisingly, a sailboat is anchored when Aomi arrives. The narrow cove, Dorian Bay, lies along the coast of Wiencke Island at about 65 degrees south.

The sailboat, named Cocorli, is about 10 meters long and built of dull, silvery aluminum alloy.

For some reason, there is no sign of life. Even after Aomi arrives, no one appears. The cabin hatch is left open.

What’s going on? Did the crew go ashore and fall into a glacier crevasse? Or are they sick in the cabin? How long have they been here—perhaps even months?

After stopping a short distance from the silvery sailboat, I lower the dinghy into the water and begin mooring Aomi.

If I tie her bow to a rock offshore and her stern to the shore, Aomi should remain secure, even in storms.

A small rock sticks out of the water offshore. However, if I tie Aomi to it, she will be too close to the silvery boat, risking a collision.

Reluctantly, I drop an anchor from the bow. I test it by pulling with the engine at full power, and it holds firm. Based on past experience, it should withstand even force-nine winds.

I also secure the stern to the shore with a 70‑meter rope. Still, the unexpected can happen. I must remember that I am in the Antarctic. I need to tie the bow to an offshore rock, as I did with the stern to the shore, instead of relying only on the anchor.

Before long, red and blue figures appear on the white shore. One of them rows a rubber dinghy over to Aomi and shakes my hand in greeting.

They are Olivier, a young Frenchman, and his girlfriend, Ketty. Inspired by a longing for the mountains, sea, and ice of the Antarctic, they spent three years preparing for their departure from Nice in the Mediterranean.

They have already spent over a month in the Antarctic and are now heading north, hurrying to return.

Standing in a rubber dinghy alongside Aomi, Olivier says in a serious tone,

“Summer in the Antarctic is over. Winter is coming soon, and we need to hurry back.”

My goodness! Aomi is still heading toward the Antarctic continent.

After a brief pause, I ask,

“Did you tie a rope from your boat to a rock offshore?”

“Of course. In the Antarctic, storms can hit with unimaginable force.”

“But according to the Sailing Directions, the seafloor here is unusually muddy for the Antarctic and seems suitable for anchoring, even in storms. Do you agree? I suppose I do not need to tie a rope from Aomi’s bow to the rocks offshore, and I can just rely on the anchor, right?”

“I think your small boat will be less exposed to the wind. By the way, would you like to join us for a cup of tea on our boat?”

After thirty-eight days alone since leaving Buenos Aires, I feel lonely. Forgetting Aomi’s safety—my top priority—I immediately reply, “OK.”

Visiting their boat in my rubber dinghy, I find the interior warm, spacious, and luxurious. It has a magnificent kitchen with an oven, berths wide enough to stretch out comfortably, a diesel heating system, and stereo speakers along the walls. Compared with Aomi’s cramped cabin, it feels like the difference between a hut and a palace.

Even so, they believed their boat was the smallest record-breaking vessel ever to visit the Antarctic.

Gathered around the table, we pop the cork on a bottle of French red wine and toast to the good fortune of meeting in such remote waters.

Time passes pleasantly as we enjoy Ketty’s French cuisine. We talk about our sailboats, our lives, the splendor of the Antarctic mountains, the intense blue of the ice, and the animals we have encountered. It is so comfortable and peaceful that I completely forget about securing the rope.

I feel dizzy from the wine. No—it’s the boat rocking. A northerly wind blowing from offshore has risen, and swells are rolling into the bay.

“Your sailboat hasn’t blown away yet.”

Their faces, as they tell a grim joke, unsettle me.

The display on my wristwatch shows it is past 10:00 p.m., but faint light still lingers outside the window.

“Oh, is it that late already? Maybe I should head back to Aomi to sleep. I thought it was only around seven. It must be the Antarctic white night, huh?”

Hurriedly, I leave the French boat and, battling a wind strong enough to sweep the rubber dinghy away, row with all my strength toward Aomi, just a dozen meters off.

When I finally break through the whitecaps and return to Aomi’s cabin, it feels cold, cramped, and bare, lacking good food or any comforts.

2. Nightmare Part I

The white Antarctic landscape quickly fades into pitch-black darkness.

The offshore wind, driving against Aomi’s bow, intensifies as the barometer in the cabin drops below 970 hectopascals, a level equal to a typhoon. A deafening scream of wind engulfs Aomi’s hull.

It has been a long time since I faced wind this strong—or is it the first time?

If the bow anchor slips, Aomi will be driven ashore in an instant. Just as I secured the stern to the shore with a 70‑meter rope, I must also tie the bow to an offshore rock with another long rope.

But the howling winds, impenetrable darkness, and swelling seas have already made it impossible to use the dinghy.

I pray for safety until morning and begin to nap in my berth, rocking violently as I endure the screams of the gale-force winds.

In the middle of the night, I wake suddenly and look at the depth sounder’s neon display. It shows less than 3 meters of water. Alarmed, I check the compass on the wall and realize that the bow had been pointing nearly north toward the offshore but has completely shifted to the west.

This means the anchor has slipped, causing the hull to turn sideways to the wind and drift toward the rocky shore. This is disastrous.

I rush out of the cabin, unsure if this is a nightmare or reality. In the pitch-black darkness, I cannot even see my own hands or tell where Aomi is.

I grab my searchlight and sweep it through the darkness. The shore should be 70 meters away, yet the black rocks and snow-covered beach appear just ahead.

Shocked, I swing the light in the opposite direction and spot the French boat, once alongside me but now only a small outline offshore.

“Aomi is really being swept away.”

Soon, the depth sounder shows just 1.5 meters. Before I can react, Aomi’s bottom crashes into the rocks, sending shockwaves through the cabin. To make matters worse, a powerful crosswind pushes the hull and mast toward the shore, tilting Aomi sharply as if to overturn her. As the waves rise and fall, they lift and drop the hull violently, hammering it again and again against the rocks.

There is no way out. At any moment, in the total darkness, Aomi could overturn on the rocky shore, and seawater at minus 2 degrees Celsius would rush into the cabin.

When morning comes, and the storm subsides, will I be able to ask the French boat to pull Aomi off the rocks?

Probably not. By dawn, the sharp edges of the rocks will puncture her hull.

No, I can’t let that happen. Somehow, by any means, I must overcome this crisis. A small single-cylinder engine without an electric starter is unlikely to help in winds this strong, but I have to try.

But the engine will not start in the cold. Gripping the starter handle tightly in one hand, I crank it, but it spins uselessly.

Aomi’s engine, which I’ve maintained, overhauled, and inspected—pouring my heart into every step—shouldn’t fail. It can’t fail.

I pour a small amount of benzene into the air intake and grip the iron handle, stiff and heavy to turn. Using all my strength, I crank it several times, but the engine still will not start.

Refusing to give up, I try again two, three, four times, pausing to catch my breath after each exhausting attempt.

Finally, on the fifth attempt, the engine roars to life. I rush out of the cabin, grab the helm on deck, and steer Aomi away from the shore.

After a few minutes, the intervals between the rocks striking Aomi’s bottom gradually lengthen and then stop. She is slowly pulling away from the shore, fighting against the strong wind and swell.

But where can I go in this impenetrable darkness and raging storm?

3. Nightmare Part II

For now, I push forward with the engine and call out to the French boat for help.

Their boat is secured by two long ropes tied to the shore and two other ropes stretched to rocks offshore. Even if I tie little Aomi alongside their boat, both should remain secure from being swept away.

Fighting against strong winds and waves, I push the engine to its limit, desperately trying to reach the French boat. But it feels hopeless. Even when I manage to make it halfway, the wind is too strong to finish the final 10 meters. I am so close, yet I cannot go any further.

Each time the wind and waves push Aomi back toward the shore, I rev the engine hard, making it roar as if it might break. I desperately try to move forward.

Still, no matter how many times I try, it is no use. As I get within 10 meters of the French boat, Aomi suddenly stops as if held back by an invisible force.

Unable to move forward, Aomi loses rudder control and begins drifting sideways. If Aomi’s fast-spinning propeller strikes the long rope connecting the French boat to the shore, it could cut the line instantly.

Just then, a scraping sound echoes from Aomi’s hull. The propeller is cutting the rope!

Startled, I pull back the speed lever. Instantly, Aomi loses forward power and drifts toward the shore in the darkness.

“Aomi will hit the rocks again—I need to do something. Anything!”

Panicking, I push the speed lever forward and try once more to reach the French boat, battling the gusting wind and crashing waves.

But something feels wrong. It is only 10 meters to the French boat, but I cannot go any further. It is as if Aomi is a dog held back by a rope, unable to take even one more step forward.

“Rope? A dog’s rope? No… it’s Aomi’s rope!”

I swing my light to the water behind me and spot a white line stretching from the stern to the shore. That is the 70‑meter rope tying the stern to land. In the chaos of the darkness and my panic, I completely forgot about it.

Hurriedly, I untie the rope, toss it into the water, and push forward at full speed again. In the impenetrable darkness, where I cannot distinguish the sky from the sea, I flash a powerful 240,000‑candela searchlight desperately. Startled by the brilliance of my searchlight, Olivier and Ketty rush out onto their deck.

Aomi moves closer and closer to the French boat, battling fierce winds and waves, nearly pushed back to shore several times.

Even after coming alongside, the waves and swells toss the two boats violently, slamming them into each other again and again.

“Quick, throw me a rope.”

They shout against the screaming wind in the darkness. I immediately throw a rope from Aomi’s stern to secure her to the French boat. I rush to the bow and hurl a second rope as well.

“Ah, this is fine. I’m saved. I barely escaped disaster.”

Relieved, I sweep my light across the surroundings. Then I spot a serious problem. One of the four ropes securing the French boat to the shore and offshore rocks has been cut, likely by Aomi’s spinning propeller.

I aim my searchlight at the water beside us, and a glistening black rocky area emerges from the darkness. With one rope gone, the two boats tied together are being swept toward the rocky bank.

Soon, we will be on the rocks. We will be lifted and dropped by the waves, slammed into the jagged edges again and again until the hulls are torn open. If both boats become unable to sail, the three of us will have to spend the entire winter here in the Antarctic.

Overwhelmed by despair, we stand motionless on deck. But fortunately, the remaining ropes hold, stopping the two boats just short of the rocks.

If the wind picks up or another rope snaps, both boats will be driven aground.

“I’ve had enough of the Antarctic. If this is a nightmare, I want to wake up now.”

I cry out from my soul into the darkness, where the fierce north wind howls.

4. Storm Passed

As a white morning dawns over Dorian Bay, the overnight storm subsides, leaving small waves rippling across the water where two sailboats float.

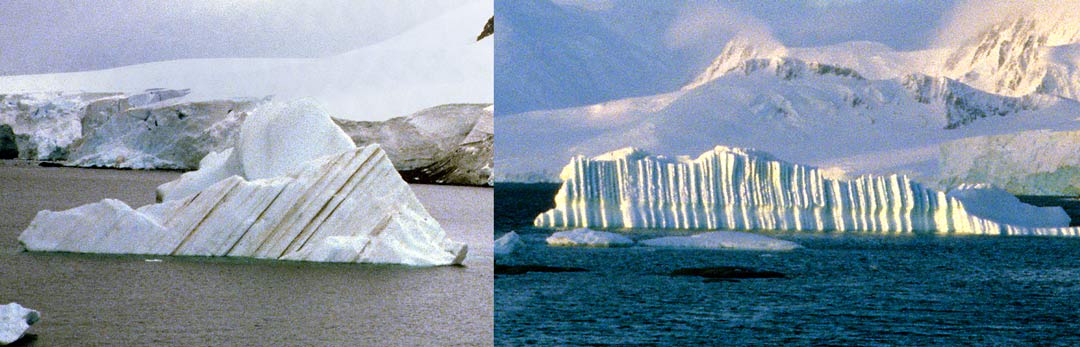

Several icebergs, driven by strong winds, are stuck in the shallows at the mouth of the bay, arranged like a magnificent exhibition.

Some are blue icebergs marked by rough vertical stripes, as if scratched by giant iron claws, while others are pyramid-shaped with brown parallel lines, resembling the layers of the earth.

These distinctive features should reveal the origin of each iceberg. They begin as seawater, evaporate into the sky, fall as snow, solidify into ice, become glaciers, travel across the land, and eventually melt back into the sea—a journey that spans tens of thousands of years. In the grand history of Earth, their astonishingly long lives may have repeated tens of thousands of times.

As the wind calms further in the afternoon, I row my dinghy to shore, step onto a black, rocky beach scattered with whale bones, and walk onto the white expanse.

On the eternal snow, so dense that it leaves no footprints, lies the body of a seal almost 3 meters long. It is a Weddell seal with silvery fur and a spotted pattern, reportedly weighing about 500 kilograms.

As I slowly approach, it lifts its head and gazes at me. Its round eyes and dog-like face, with whiskers, remind me of my middle school classmate Shiraki-kun.

Farther across the dense snow, I step over a narrow stream of melted snow, climb a white slope, and reach an ice ridge.

The view ahead is of a sea chilled to pale black and a cold, leaden sky. Along their border, pure white icebergs drift.

The landscape resembles a black-and-white photograph, entirely colorless. Everything feels clean, as if the dirt in the air has frozen and fallen into the sea. I walk slowly up the white slope, lost, my mouth open, unable to think of anything. If I step too close to the glacier’s edge, I could fall into a crevasse.

Back on the beach, I head toward the penguin colony. The rocky areas where penguins raise their chicks in summer now lie quiet. Scattered across the area, they stand motionless, each about 60 centimeters tall. Their white chests are outstretched as they gaze out to sea, brushed by the remaining winds of the storm.

Born into this desolate, icy world, what do they think? What do they seek each day? Will they grow old and one day return to the sea to become part of it?

When I walk closer, they hurry away, avoiding eye contact. They are Gentoo penguins, known for the white triangular patterns on their foreheads that resemble eyebrows, and for their bright orange beaks, which stand out against their black-and-white bodies. A strong smell, like dried fish, fills the area.

The next day, a snowy wind continues to sweep across the waters of the small Dorian Bay. Hoping for better weather, we postpone our departure. Yet by the morning of the fourth day, there is still no break in the thick snow clouds overhead.

Nevertheless, the French boat decides to set sail. Even in poor weather, they can take turns keeping watch for icebergs, since there are two of them.

“I hope we meet again in Buenos Aires, if we both can return safely to South America.”

I shake their hands as they leave the Antarctic, one step ahead of me, and promise that we will meet again.

But now, summer is over. There is no guarantee that little Aomi can escape the freezing Antarctic waters, cross the stormy Drake Passage, and return safely to South America. I might be blinded by a white blizzard, crash into an iceberg, become trapped in the frozen sea, or be overturned by a large wave.

Feeling a cold sweat on my back, I keep waving at the French boat as it disappears into the vast Antarctic landscape.

This is no ordinary voyage, even for their larger boat. A few weeks later, it capsizes near 50 degrees south, breaking its mast.

Hi! Any questions or suggestions about the content are greatly appreciated.

I’d also love writing tips from native English speakers. Since English isn’t my first language, if you notice any awkward phrases or anything that seems off, please let me know.

Thank you!

E-mail