31. Beyond Ice

Having fulfilled my dream of landing on the Antarctic continent, I feel no regrets.

Yet, for some reason, I am compelled by an unseen force to see how far south I can go along the Antarctic Peninsula, where winter is swiftly approaching.

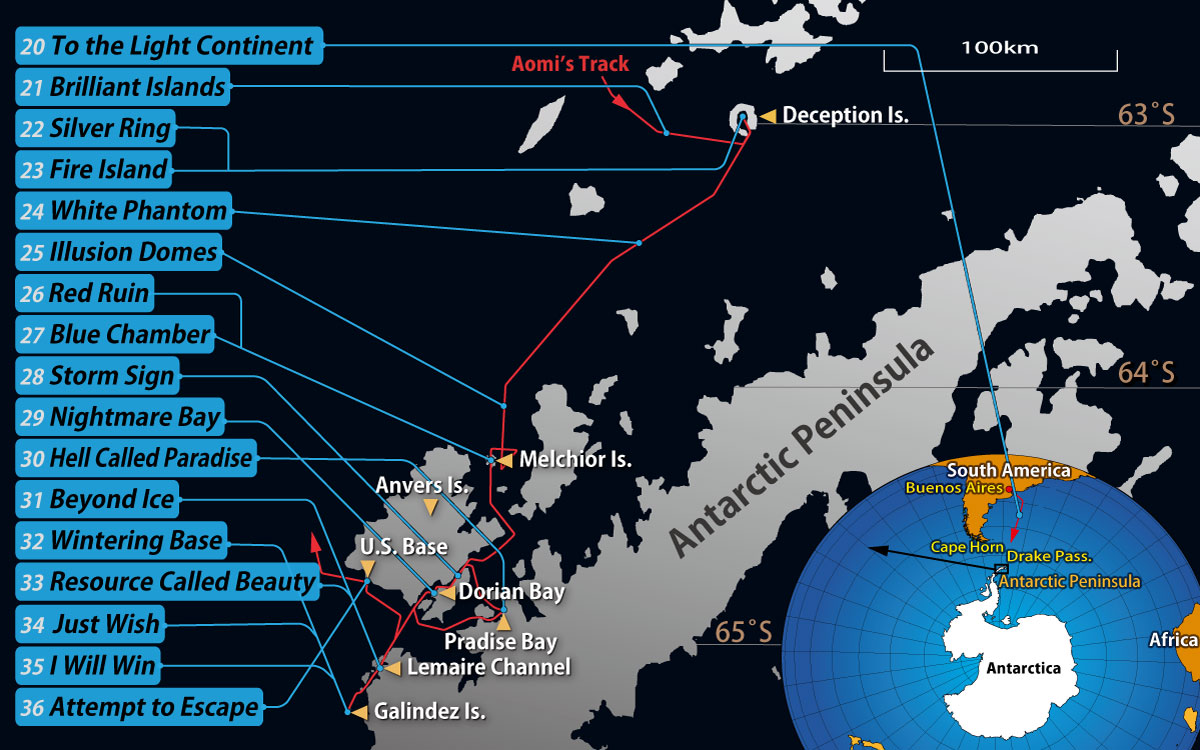

At 10:00 a.m., with the sun climbing steadily in the northern sky, Aomi sets sail for Galindez Island, 60 kilometers to the south. Beneath clouds that suddenly fill the sky, strong winds and tides clash, whipping up ominous triangular waves.

Soon, a sharp, knife-like cut appears in the mass of icy mountains stretching across the blue horizon ahead.

“That's the entrance to the Lemaire Channel!”

The channel, a narrow passage through a valley, stretches about 15 kilometers and is often described as one of the most beautiful places in the Antarctic.

This site is also known as Kodak Valley, probably because visitors, captivated by the breathtaking sight of steep mountains rising from the water, all aim their Kodak cameras at the view from the deck in unison.

With northerly winds filling her sails, Aomi reaches the mouth of the Lemaire Channel, and I raise my binoculars to scan the narrow passage. Unfortunately, the far end of the river-like surface ahead appears choked with ice, leaving no room for navigation.

This may be only an illusion caused by distance. As I approach, I hope gaps between the ice will begin to open.

I start the engine, lower the sails, and cautiously proceed along the valley floor.

But no matter how close I come, the ice ahead remains tightly packed, with no gaps appearing. Eventually, Aomi reaches a vast, white expanse—a wilderness of dense ice.

Clear ice ten centimeters long, white ice the size of barrels, and blue-white blocks several meters long fill the valley. There is no way forward.

It has already been five hours since departure. If I turn back against the northerly wind, the sun will surely set along the way, putting Aomi at risk of colliding with rocks and ice hidden in the darkness.

Since I can't turn back, since I can't retreat… I've no choice but to push forward.

Determined to move on, I hurry up the 17 steps I had carefully designed, built, and attached to the mast in Buenos Aires for Antarctic use. I scan the ice field from the mast-top, 10 meters above sea level.

The water at the bottom of the valley, with steep mountains rising on either side, is filled with countless pieces of ice of all sizes, leaving no room to pass.

Is it still impossible to advance?

I strain my eyes and spot a black, circular pond-like opening in the white ice field ahead. By pushing through smaller pieces of ice and steering clear of larger chunks, Aomi might be able to reach that black pond. I climb down from the mast and press the bow into the ice field.

At once, Aomi and I are engulfed by the deafening sound of ice grinding against the hull. Numerous pieces of ice, sharp as glass, strike the bow, scrape along the hull, and drift aft one after another.

Each time an ice floe weighing hundreds of kilograms crashes into the hull, both Aomi and I shake violently, and the impact echoes through the aluminum mast. I fear a hole might open at any moment, despite the stainless-steel reinforcements added to the hull.

Twenty minutes later, as Aomi reaches the black pond that has opened in the ice field, I climb the mast once more to survey the path ahead.

This time, the view fills me with despair. Countless blue-white ice blocks, large and small, are packed more tightly than ever.

Even if Aomi could move forward, she would become trapped in the ice field, and her hull could be crushed under the enormous pressure of ice driven by wind and tide.

Clinging to the mast, which rises sharply into the sky from the bottom of the valley, I strain my eyes for a way forward. Then, as I suspected, there is nothing ahead but white ice; the black surface of the water is nowhere to be seen.

Trapped in the ice field, will nightfall come before I can find a way out?

Gripping my binoculars, I desperately scan the endless white surface around me, straining my eyes again and again without giving up.

Then, a few hundred meters from Aomi, near a cliff along the channel, I spot a faint black line running like a stream.

If I can reach that narrow lead—a ribbon of open water—Aomi might be able to escape the Lemaire Channel!

Hurrying down the mast, I seize the tiller and force the bow against the white edge of ice from inside the black pond.

No! The ice is far too dense.

The hull digs into the ice field but soon stops, as though it has run out of strength.

If only Aomi could reach the surface of that black, creek-like water, I could escape the channel—but …

I glance up from the white ice field. The sight of mountains towering nearly 1,000 meters on either side of the waterway strikes my eyes with vivid, breathtaking clarity.

The peaks are too steep for snow to stick, but it gathers in the narrow crevices that cut across the slopes, forming a delicate white web over the black rock faces.

In the crystal-clear, cold air, the mountain cliffs rise with almost divine majesty, beautiful and overwhelming.

Hi! Any questions or suggestions about the content are greatly appreciated.

I’d also love writing tips from native English speakers. Since English isn’t my first language, if you notice any awkward phrases or anything that seems off, please let me know.

Thank you!

E-mail