This episode can be read on the "To the Light Continent" page.

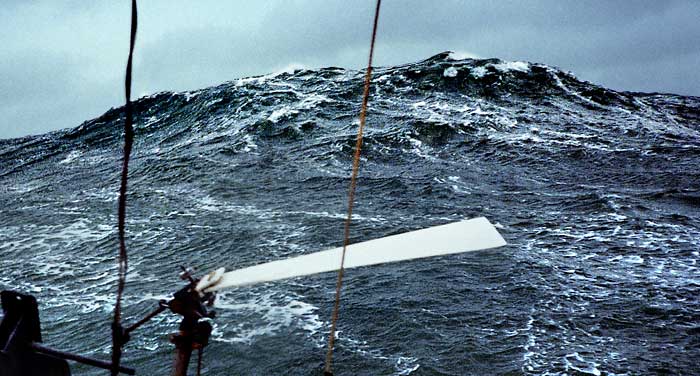

After departing from Buenos Aires, the capital of Argentina, Aomi headed towards Antarctica but capsized in the rough seas of the South Atlantic, losing her mast.

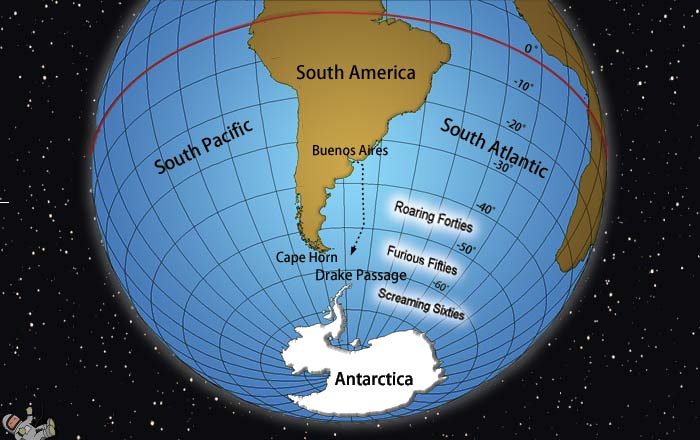

The South Atlantic is notorious for its rough seas. As shown in the figure below, the waters beyond 40 degrees south latitude are called the Roaring Forties, those beyond 50 degrees are known as the Furious Fifties, and those beyond 60 degrees are referred to as the Screaming Sixties. Sailors have long feared these treacherous regions.

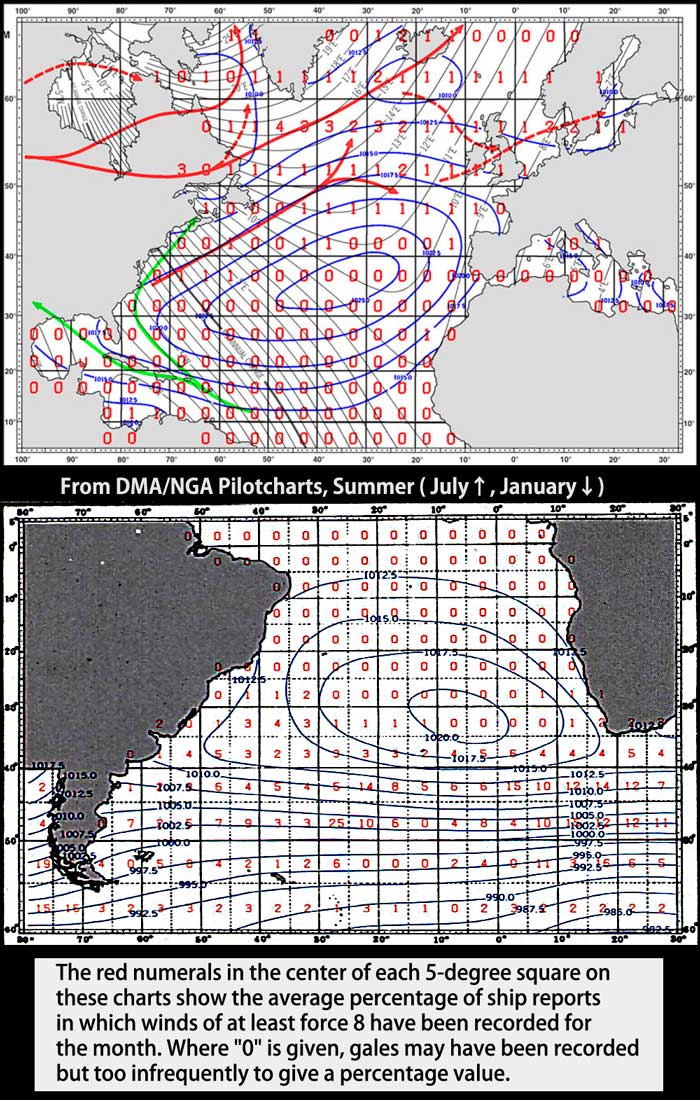

The charts below, sourced from pilot charts, indicate the percentage of storms (winds over force 8) during the summer in both the North and South Atlantic, shown in red numbers.

To compare, let's first look at the frequency of storms in the North Atlantic. On routes crossing the North Atlantic, the occurrence of storms is almost always 0 or 1%, which is relatively low. (However, for small sailboats, even force 6 winds can feel like a storm.)

In contrast, the Southern Hemisphere presents a completely different scenario. The red numbers on the lower chart indicate that in some areas, storm frequencies reach as high as 25%. For example, if you sail from South America to Antarctica, starting from Buenos Aires, you must navigate through regions with storm frequencies ranging from 5% to 7%.

What causes the difference in storm frequency between the North and South Atlantic? The explanation can be found in the middle of the "Exploding Waves" page. Please have a look.

*

With the mast broken, I had to abandon my voyage to Antarctica and return to South America, the nearest continent. However, without a mast, setting sails was impossible. Aomi has a small 3.5-horsepower diesel engine, but it is only suitable for entering and leaving harbors. Additionally, in the open sea with relatively large waves, the propeller doesn't function well because the boat's bottom rises and falls, disrupting the water flow around it.

Moreover, the limited load capacity of a tiny sailboat like Aomi makes it impossible to carry enough fuel.

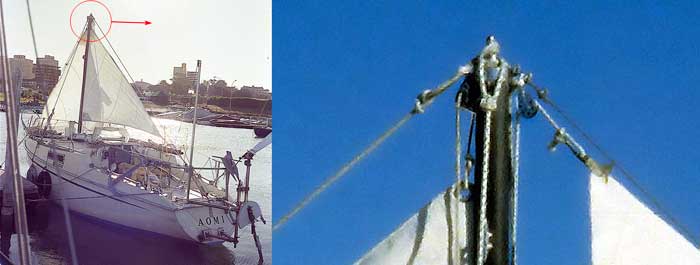

So, I improvised an emergency mast, known as a jury mast. The photo below was taken after arriving at the port of Mar del Plata in Argentina. Two sails were hoisted in front of and behind the short mast, made using the boom, making Aomi look like a yacht.

The picture on the right shows a close-up view of the mast top.

The wire securing the mast is only at the front, while the supports at the back, left, and right are ropes. You can also see the halyards attached for hoisting the sails. I thought it was quite well-made for a jury mast, and I was pleased with it.

However, upon arriving in Mar del Plata with the jury mast, I found that there weren't enough materials or facilities available to repair Aomi. So, I decided to take her to Buenos Aires, where I was familiar with the area and had a part-time job, allowing me to make repairs while earning money.

*

The photo below shows the lower quarter of the broken mast on the ground at the yacht club in Buenos Aires. The rest sank into the sea, but I managed to bring this section with me.

For the Antarctic voyage, steps were attached to the sides of the mast for climbing up to watch for ice and navigate through it. These steps are the triangular objects seen in the photo above. They were attached with rivets, but the holes caused damage to the mast.

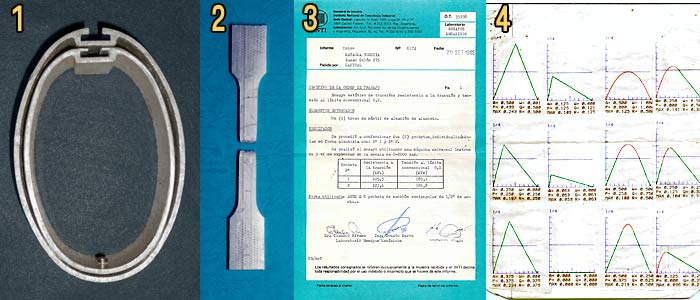

Therefore, the dimensions of the new mast were carefully calculated for strength, and the ice-watching steps were designed so they wouldn't weaken the mast. Additionally, due to the limited materials available, it was necessary to make the mast a double structure, as shown in photo #1 below, to maintain its strength. (Of the total length of 9 meters, the double structure extends approximately 3.2 meters, reinforcing the section subjected to the most strain.)

Photo #2 shows a test piece from the mast strength test conducted at the National Industrial Testing Laboratory in Argentina. First, it was cut from the new mast using a machining process. Then, the top and bottom edges were pulled, causing the piece to break in the middle. Photo #3 displays the test result certificate, and photo #4 shows the output from my small computer used to calculate the force distribution on each part of the mast.

After nearly a year of repairs and part-time work, I was finally able to raise the new mast on Aomi and set out again, heading south across the South Atlantic towards Antarctica.

*For details about the capsizing accident that broke the mast and how I managed to return, please read the "To the Light Continent" page.

The background of this page is a photo of snow taken in the Antarctic.