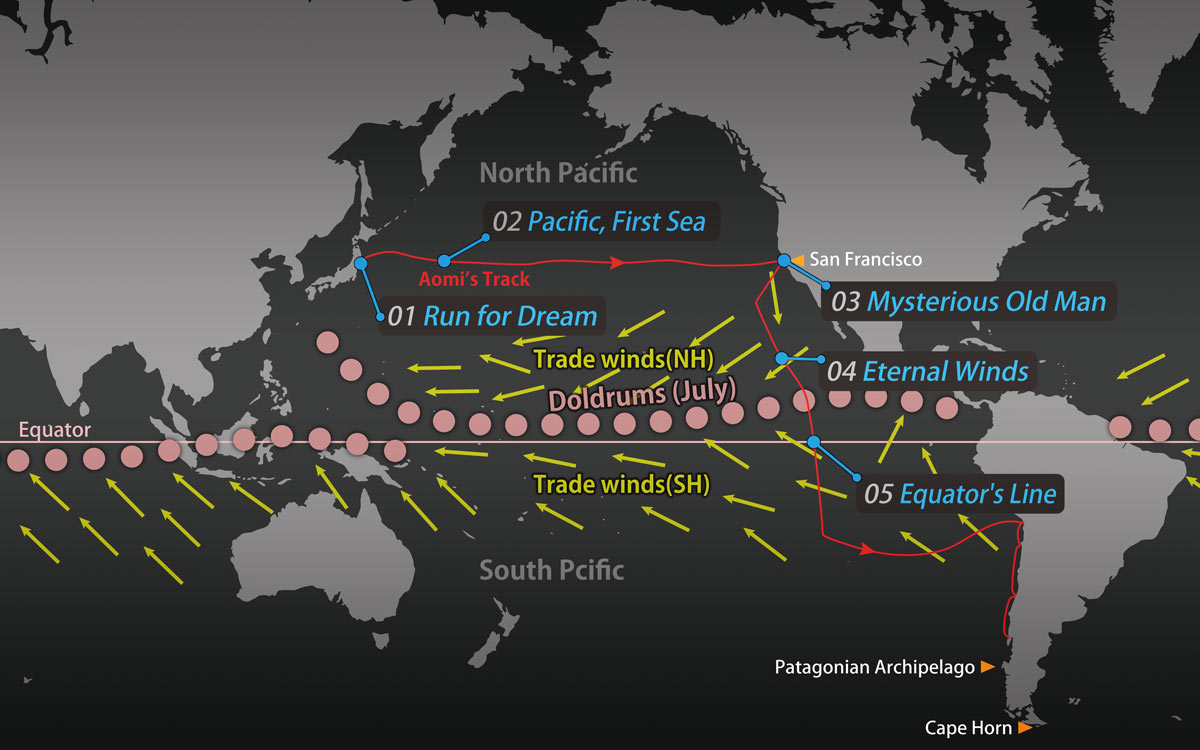

05. Equator’s Line

The same name does not always mean the same thing. Even within a single country, climate and culture can vary dramatically from place to place. Likewise, the vast waters of our planet—whether called seas or oceans—each possess a distinct character.

After crossing the equator, Aomi and I sail through waters completely unfamiliar to us.

On the day Aomi crosses the equator, I see a red line stretching across the sea.

Like the equator on a map, the red line runs from east to west, as far as the eye can see. It is astonishing to witness such an imaginary concept appear so vividly in the real world. But when I look more closely, I notice that the line’s thickness varies, breaking in places. Surprisingly, it is a dotted equatorial line!

While crossing it and breathing in air that smells of fish, I reach out from the deck and scoop up water with a ladle, gripping its long handle. Tiny red balls, a school of fish eggs, float along the boundary where ocean currents meet.

It has now been a full month since I departed from San Francisco. Still, Aomi continues on her course, heading steadily south across the South Pacific. The trade winds of the Southern Hemisphere now blow head-on at force five or six, causing Aomi to pitch uncomfortably.

The Southern Cross rises higher in the night sky each day. I like these bright stars because they do not form a perfect right-angle cross; they tilt.

Thousands of miles away from city lights, countless stars cover the sky, filling every gap between them. The galaxy above is a vivid band of light.

When I first began my voyage, I mistook the Milky Way for a band of clouds. But I eventually realized it was a galaxy as I saw it in the same place every night. Now, with only the naked eye, I can even see how this beautiful river of light splits into wide, branching streams.

It is no wonder that people once called it the Milky Way. This is the sky they gazed upon, before electric lights were invented about a century ago and began to brighten the night.

I lift my binoculars and point them toward the galaxy. How many stars there are, scattered across the sky! How far away is each one?

Five hundred years ago, during the Age of Exploration, people bravely sailed wooden ships into unknown seas that seemed infinite, where demons might await them.

Someday, people will sail this endless sea of stars in ships called spacecraft. As one mystery after another is revealed, they will send their hearts toward even more distant stars.

That era of space exploration may still be centuries away. I will never see it. And there is no guarantee that humankind, with its ever-growing population, will survive to witness it.

Aomi’s destination is Chile, a country on the South American continent. It is a long, non-stop, three-month journey from San Francisco, especially for a tiny sailboat only 7.5 meters long.

In the small cabin, I have somehow managed to store 14 ten-liter plastic bottles of water. That allows just 1.5 liters per day. I use this water to cook rice, make miso soup, drink tea after meals, and brush my teeth before bed.

However, I use seawater to rinse the rice before cooking. Each day, I light the kerosene burner and cook three cups of rice in a pressure cooker, which helps save both water and fuel by reducing cooking time. Sitting on deck with a gentle breeze around me, who could resist tasting hot, freshly cooked rice—along with the sea air? One Umeboshi, a Japanese pickled plum, is enough to empty a large bowl.

The vegetables on Aomi last much longer than I expected. Potatoes, onions, and even the carrots and cabbages seem to stay fresher than they would on land. This might be due to good ventilation or the boat’s motion. Even without a refrigerator, I can eat raw eggs for up to three weeks after departure, perhaps because I coated their shells with petroleum jelly (Vaseline).

When fresh vegetables run out, I put mung beans in plastic food containers and start making bean sprouts. Each morning and evening, I sprinkle them with a little water. After four days of growth, I stir-fry the white sprouts for miso ramen or simply chew them raw for their fresh, crisp taste.

I also test a canned salad made from dried vegetables, bought in the United States, originally prepared as emergency food for nuclear war. Inside are dried pieces of cabbage, carrots, and celery. After soaking in water for a few hours, they return to their original form as a cold vegetable salad.

In San Francisco, I also stocked Aomi with long-lasting food supplies: powdered butter, powdered eggs, dried soy meat, instant rice, and packaged tofu said to last up to a year. From my experience crossing the North Pacific, I have learned that the most enjoyable part of life at sea is eating. I have also discovered that my tastes at sea are different from those on land.

After 80 days alone at sea, Aomi is now just a few hundred kilometers from her destination, South America. Here, I encounter the Peru Current: a large, cold stream running northward along the continent. The blue sea around Aomi suddenly turns green, and heavy, gloomy clouds blanket the sky.

A few mornings later, an eerie landscape surrounds me. Milky-white and rust-colored disks, over 50 centimeters wide, dot the green sea as far as the eye can see, stretching all the way to the horizon. The number is astonishing. An abnormal outbreak of jellyfish, likely tens of millions, seems to have occurred. Will any species, including humans, eventually reach its limit and collapse?

Aomi floats in this soundless jellyfish sea as a calm sets in. I am surrounded by an eerie stillness, an unknown fear, and a loneliness. It is the first time I feel lonely at sea.

After about two days, Aomi sails out of the jellyfish swarm and continues toward the looming continent. Since entering the Peru Current, the sky has remained overcast. Even at midday, it feels like evening. Without measuring the sun’s altitude with a sextant, I cannot determine my position. I wonder where Aomi is heading.

By my calculations, Aomi should have reached land. I search for the lighthouse through the night, hoping to spot it tonight, or even within the hour. I scan the black horizon. There is nothing.

Strange. Could the currents have pushed Aomi backward? How many more days until landfall? I have only three cups of water left.

Anxious night after night passes. The moon remains hidden behind the clouds, casting a pale white glow over the entire sky.

When morning arrives, the sea becomes a vast zoo of birds. Many species, large and small, fly in all directions. Pelicans also glide in powerful formations.

Some birds suddenly freeze in midair, then plunge straight into the sea. It takes me half a day to realize they are fishing.

The countless birds clearly signal that land is near. At night, I see white dots of light on the horizon. I grab my binoculars and study the lights closely. They are not ship lights. Their regular alignment clearly shows a road.

This is my first glimpse of land in three months. South America lies before me, a world completely unknown. I cannot speak the language. I have no idea what awaits me.

After sailing along the Chilean coast and through the Patagonian Archipelago,

the long-awaited, legendary Cape Horn is finally within reach.

Hi! Any questions or suggestions about the content are greatly appreciated.

I’d also love writing tips from native English speakers. Since English isn’t my first language, if you notice any awkward phrases or anything that seems off, please let me know.

Thank you!

E-mail