03. A Mysterious Old Man in San Francisco

When faced with two choices, which path should one take? The easy road or the difficult but rewarding one? A secure future or a life full of adventure? Leave it to chance or carve out your own way?

In the first foreign country I ever visited, I had to make such a decision.

1. My Life Abroad 2. John’s Secret 3. Returning to the Sea

1. Starting My Life Abroad

“Now, it is time to begin my life abroad!”

Since I have come all the way to the United States, I want to travel across this vast country, which is 25 times the size of Japan, and see the Grand Canyon and Niagara Falls.

But I cannot afford it. I need to carefully strengthen Aomi, my sailboat, to prepare for my next destination: Cape Horn in South America, notorious for its violent storms. I must buy many materials for the modifications, and I am likely to run out of money soon.

In early October, four days after arriving in San Francisco, I visit an auto repair shop in search of a job as a mechanic. I am rejected there, but I meet a Japanese customer named Mr. Kawasaki.

He is in his mid-fifties and a survivor of a kamikaze suicide mission during the Pacific War. Shortly after the war, for some reason, he immigrated to the United States. Now he works as a gardener and needs helpers.

Eventually, I stay at his house in Cupertino, a suburb of San Francisco, and begin working the next day.

Early in the morning, under the clear California sky, deep blue as if dyed with indigo, I leave home with Mr. Kawasaki. Upon arriving at the customer’s yard in our small truck, I strap an engine-driven garden blower to my back and hold the pipe in my hand. I blow the leaves and debris that litter the yards, gathering them into piles.

The blast of wind is so strong that my small body nearly topples backward. What a powerful cleaning job it is! Before I get used to it, I struggle to control the direction of the wind, sometimes scattering the trash or blowing it into the neighbor’s yard, which seems to trouble Mr. Kawasaki, though he shows little outwardly.

After cleaning the yard, I use a lawn mower to cut the grass. As I work, I notice many plants, flowers, and trees I have never seen in Japan. Even the weeds look so exotic that it feels almost a shame to pull them out.

The nearly twelve hours of sweaty, dusty work each day do not seem so hard when I think of my dream—Cape Horn. After work, I have dinner with the four members of the Kawasaki family, then go to my room to study charts and documents about Cape Horn late into the night.

About two months into the job, San Francisco’s winter rainy season arrives. With no gardening work available, I lose my source of daily income. I begin working in Mr. Kawasaki’s garage, repairing trucks and lawn mowers to earn some money.

But before Christmas, as I begin preparations for Aomi, I pack my belongings and leave the Kawasaki family, who have taken such good care of me.

2. John’s Secret

My new address is Pete’s Harbor, founded by Italian immigrants in the delta, about a third of the way from the far end of San Francisco Bay.

Anyone who walks here senses that the place is filled with dreams. Sailboats are under construction all along the coast. People who have longed for the sea are now building their own large sailboats. There are students in their twenties, old men living on pensions, families working hard together, and many who have sold their houses to fund the construction and now live on their unfinished sailboats.

With the help of their knowledge, especially their power tools, I prepare for the Cape Horn challenge. A successful crossing of the Pacific Ocean does not guarantee that I can sail to Cape Horn. To face the world’s roughest seas, I must be fully prepared and watch for even the slightest weakness in Aomi.

I reinforce the cabin windows with extra layers of plastic to protect them from the impact of large waves. I also rebuild the rudder to make it stronger and inspect the mast’s metal fittings for fatigue, using dye and a magnifying glass. There are over 30 items on the list for inspection, maintenance, and strengthening. One careless mistake, or even a small compromise, could sink Aomi and me in the stormy sea.

I see a strange old man in the harbor. He is tall, robust, with piercing eyes. Always dressed in a white shirt and a green beret cap, he is highly intelligent and sharp-tongued. Living alone on a large 14‑meter sailboat, he has no friends, no family, or no visitors. Some say he once worked for the CIA.

The old man named “John” comes to visit me on Aomi. I follow him along the pier. Suddenly, John turns to whisper in my ear.

“Never tell anyone what you’re about to see on my boat. Swear to God?”

He brings his hands together over his chest, as if to pray, while I struggle to find an answer. Why is he taking me on his boat if he wants to keep it secret?

“If people find out what I’m going to do, they’ll call me crazy. But you’ve crossed the Pacific alone—you’ll understand.”

The cabin of his large sailboat, moored at a floating pier, is perfectly equipped: a hot water shower, a kitchen with a three-burner stove, and the latest electronic navigation system. Next to the bookshelf is a high-powered Japanese radio, a model not sold in Japan. Nearly a hundred used pens and pencils are neatly aligned on the chart table, something unusual.

He has been saving money for 25 years to prepare for his voyage. I wonder where he is going and what he plans to do.

He shows me materials for my Cape Horn voyage, pulling dozens of detailed maps, charts, and satellite photos from the shelves. Why does he keep all this material? I notice “Central Intelligence Agency” printed in small letters in the corner of a map. For a moment, I am startled.

John looks up sharply from his desk and asks,

“Why are you going to Cape Horn?”

“I do not know. But the sea teaches me something important, something the city cannot.”

As if discovering a truth, John murmurs,

“Yes, no one who goes to Cape Horn knows why.”

He plans to leave the harbor within two months, head south, and never return.

“I’ll go somewhere—and die somewhere.”

He says this, pausing for a moment, with a firm yet sad expression. What is he thinking? It is not only strange; it is mysterious.

“John, where are you going?”

He grabs a piece of paper from the desk and quickly writes down two sets of numbers, the first being 56. Before I can see the second, he crumples the paper and tosses it into the trash.

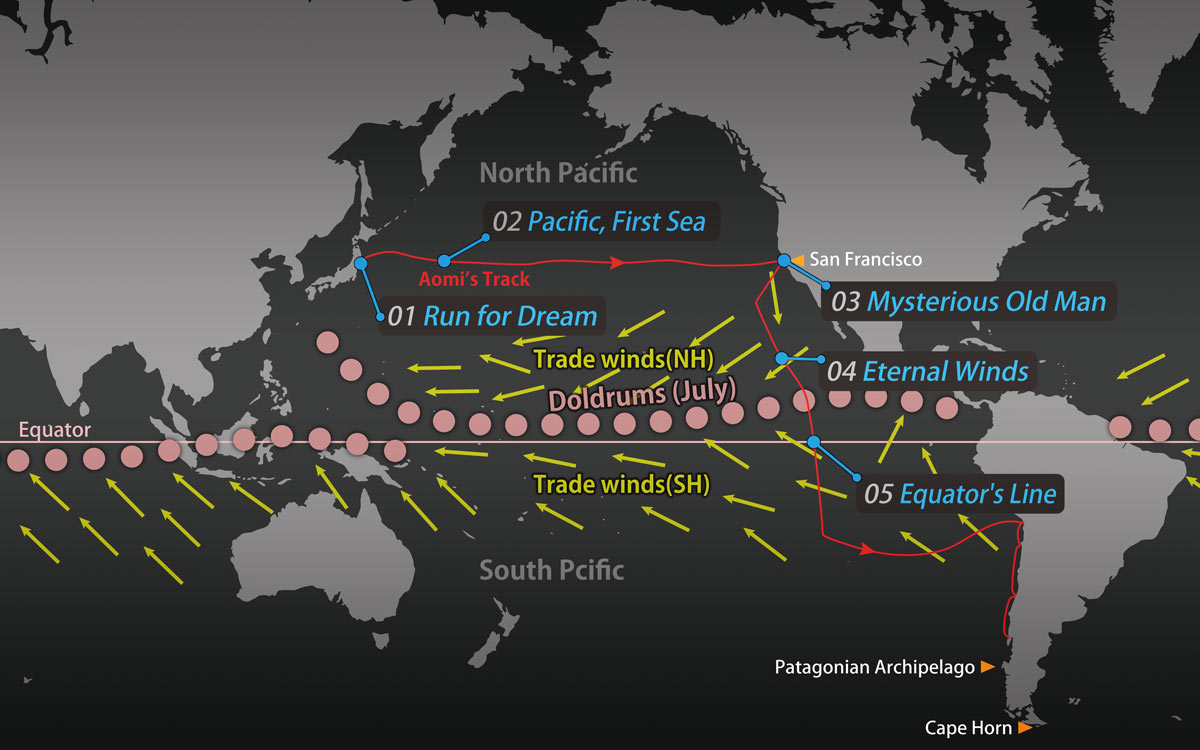

56°S, 67°W: Cape Horn, the southernmost tip of South America, projects at the meeting point of the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. Before the Panama Canal opened in the early 20th century, the rough seas around Cape Horn were known as the only route between the two oceans, and a deadly, terrifying graveyard of ships.

Countless ships vanished here, struck by unimaginable storms, making Cape Horn a centuries-old symbol of maritime terror.

While reinforcing Aomi, I frequently visit John’s sailboat to discuss the two main routes to the legendary Cape, with the chart spread out on his cabin table before us.

John speaks with strong conviction:

“The risk of distress is too great if you sail far south along the Pacific coast of South America to Cape Horn, the continent’s southernmost point. The huge, crashing waves would easily swallow your small boat in the stormy seas known as the Furious Fifties. But as you sail south through the Pacific, you can enter the Patagonian Archipelago, navigate between its islands, and approach Cape Horn.”

He continues with certainty:

“There, instead of giant waves, you’ll see the majestic mountains and glaciers of the Andes, along with some of the most unexplored islands on the planet. Sailing to Cape Horn through the open sea without passing through the Patagonian Archipelago would be like climbing the Himalayas with a blindfold, missing the beautiful scenery along the way. What’s the point?”

In the Patagonian region of southern South America, a chain of islands stretches for about 1,800 km. Sailing books describe this area as largely unexplored, with winds coming down from the Andes, strong enough to hurl stones into the air, currents reaching nine knots, and numerous reefs. Attempting this passage alone, I would surely face danger. I turn to John and reply,

“No. If I sail through the rough open sea, I can experience huge waves and a sea of terror.”

John counters firmly,

“You’ll encounter plenty of those in the South Atlantic after passing Cape Horn. What’s the point of seeing the crashing waves in that sea of hell?”

“It helps me think about life,” I reply, firm in my conviction.

John looks puzzled for a moment, then shakes his head.

When sailing the open sea to Cape Horn, my survival depends entirely on luck. In the notorious Furious Fifties, if Aomi were to capsize and lose her mast in rough seas, sailing would be impossible. She would undoubtedly sink if her 5‑millimeter reinforced plastic hull broke in heavy seas.

However, whether Aomi encounters trouble in the Patagonian Archipelago depends on my efforts, caution, and navigational skills.

“Sailing the open sea means relying on luck, but navigating island waters means relying on myself.”

I repeat the words over and over, and finally make up my mind.

“Very well. I will rely on myself.”

3. Returning to the Sea

At 3:00 p.m. on May 3, after six months in the United States, Aomi, now prepared for Cape Horn, passes under the rust-red Golden Gate Bridge and leaves San Francisco Bay.

I feel heavy-hearted, though departure should be a joyful moment. I do not want to go to sea. I want to stay on land. I feel like a kamikaze pilot on a suicide mission, holding back tears and tightening the Hinomaru hachimaki, the traditional headband with the Rising Sun symbol. My feelings are now entirely different from when I left Japan last year. At that time, I knew nothing about the sea.

As Aomi sails out, a storm begins, and the land disappears on the horizon behind me. The tops of the waves start to curl forward like tongues, then crash violently over the hull. The sky and sea are uniform, gloomy gray, but the tongue of water I look up at is a transparent green, like a thick sheet of glass against the gray sky.

I quickly replace the regular jib in front of the mast with a small storm jib. Even so, Aomi heels more than 50 degrees and the cabin window is now submerged. The view of the seawater through the small acrylic window is a deep, soul-cleansing blue, hard to imagine from the gloomy gray sea. Countless white bubbles flow through the water. It feels like being inside an aquarium—or rather, inside a submarine.

My body, no longer accustomed to the boat’s motion, rejects it. Feeling like vomiting from Aomi’s constant rise and fall, I enter the cabin, peel off my oilskin jacket and pants, both drenched with spray. Collapsing onto the violently rocking berth, I lie there as if struck by a severe illness. After more than six months on land, I had forgotten what the real sea was like. Now I am back.

Seasick and groggy, lying in my berth, I begin to recall my days in the United States. I remember the days I longed for Cape Horn, working hard to earn money and remodeling Aomi little by little. I was so absorbed that I often forgot to eat. Now I realize that dreaming about the voyage from shore is the most enjoyable part of a sea journey.

The storm continues for 2 full days. The mainsail tears in two, the navigation light at the top of the mast blows away, seawater enters the cabin, and most of the food is soaked. The paper labels on the canned goods, purchased with the little money I had left, are wet and peeling, and the cans are beginning to rust.

“I was careless. I let my guard down.”

This is how the sea reminds me of itself.

The voyage to Chile, in South America, is a non-stop, three-month journey of over 10,000 kilometers, crossing the equator.

Here begins a new chapter in my relationship with the sea.

Hi! Any questions or suggestions about the content are greatly appreciated.

I’d also love writing tips from native English speakers. Since English isn’t my first language, if you notice any awkward phrases or anything that seems off, please let me know.

Thank you!

E-mail