Our Destiny on Earth

—A Talk with Professor Kohama—

1. Noah’s Ark

2. Closed World

3. Delusional Earth

4. Farming Realization

5. Shift in Priorities

1. Noah’s Ark

2. Closed World

3. Delusional Earth

4. Farming Realization

5. Shift in Priorities

● 1. Noah’s Ark ●

“That sounds a bit strange, even to me. Why are you interested in photos like this—sailing through untouched parts of the Earth and the raw beauty of nature?”

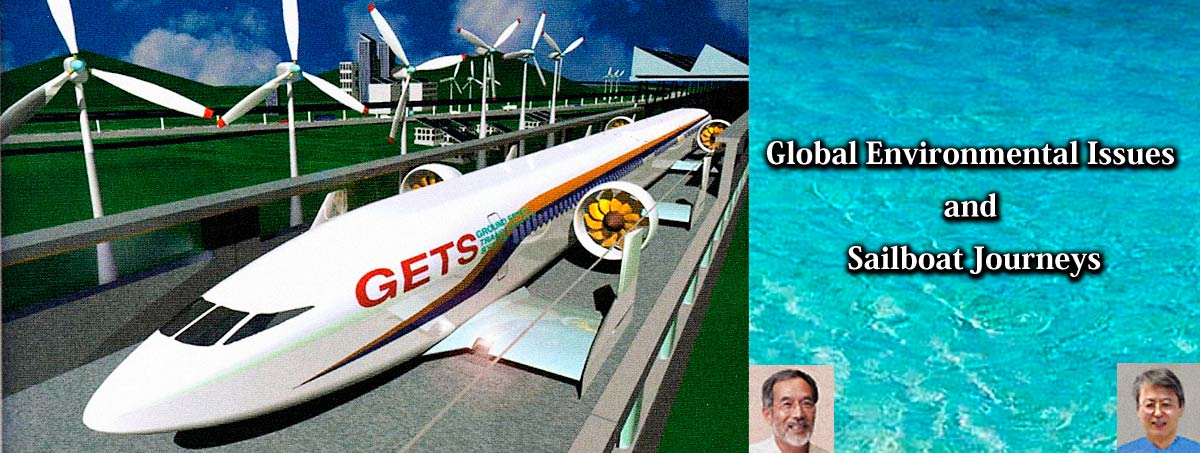

I was speaking with Dr. Kohama from the Institute of Fluid Science at Tohoku University. He’s researching the “Aero Train,” a high-speed hovering train.

“As I understand it, you embarked on this adventure entirely on your own, without any sponsors. That’s quite different from the adventures we usually see on TV nowadays.”

That’s right. I worked in different countries to earn enough money to keep sailing and continued my voyage for eight years.

“This is about the global environment, but these days, people rarely have the opportunity to experience untouched nature. I believe that only when someone encounters pristine nature, as you did, can they truly understand the extent of its pollution.”

I sailed across vast oceans alone, journeying through remote regions like South America, Patagonia, and Cape Horn, where fierce winds howled. I even made it to Antarctica on my own. I saw the Earth in ways most people will never experience.

“You sailed one of the smallest yachts ever to complete a solo circumnavigation, and I believe that by witnessing and experiencing some of the most dangerous parts of the planet, you’ve gained profound insight into the roots of our environmental issues.”

Although this voyage was completed some time ago, he believes it’s crucial for the world to hear about it now, especially with the urgency of today’s environmental issues.

Professor Kohama’s Aero Train research focuses on creating a sustainable energy system designed to minimize environmental impact.

“Professor Kohama, I believe the root of environmental problems lies in how people think and behave toward nature. I realized this after nearly ten years of sailing around the world.

“For example, we live in a human herd, in towns and cities, much like a flock of sheep. There, we laugh, cry, get angry, fight, and in the end, die—all within the herd.

“We hardly pay attention to what happens outside the city and avoid looking at it. We just don’t care. But I believe that what happens outside the herd will eventually determine our fate.”

“That’s why I want you to share these thoughts with everyone through your photos and writing. I believe anyone would find those photos shocking, even if they hadn’t experienced it themselves.”

“I’ve tried talking about these things, but no one around me seems to understand or care.”

“It’s just like Noah’s Ark. Noah tried his best to warn people that something terrible would happen if they didn’t change, but most didn’t listen. It’s the same idea. But that doesn’t mean you should stop trying to spread the message.”

“So, you mean I should keep doing it, right?”

“By the way, what inspired you to embark on such a great adventure—perhaps the greatest of your life—in that tiny yacht?”

● 2. Closed World ●

“Yachts don’t rely on fuel, which is fantastic. That’s the beauty of them.

You can sail using only the natural energy of the wind.

“I believe that even large ships—tens of thousands of tons—could potentially reach their current speeds using just wind and solar power. I’m convinced it’s possible to travel with zero emissions and no waste.”

Professor Kohama, who says this, is researching the Aero Train, a future hover train powered solely by wind and solar energy. He’s also the creator of the Aero Train.

“I have a lot of interests and have explored many hobbies, like flying airplanes, but the one I’d love to return to is yachting because it’s so profound. Yachts are like miniature spaceships.”

When I was a student, I often sailed on a yacht owned by Professor Kohama.

“Exactly. There are no grocery stores or supermarkets on the open ocean, so all the food and water I had on the yacht was what I packed before leaving port. It’s a world where you can’t rely on outside supplies—running out of food or water means you won’t survive.

“You have to live on what you’ve brought. It’s the same concept as living on a spaceship—or even on Earth. It’s a closed system, where you have to carefully manage your water, food, and resources with the future in mind.”

“Whether it’s food or oxygen, humans can’t produce these things on our own. We’ve been living on the ‘interest’ that nature provides, much like the interest paid by banks. But now, we’re beginning to use up the ‘principal’—the resources themselves.

“If this continues, my calculations suggest that, just for example, even oxygen could run out in 57,000 years.”

Later, I learned that, according to research conducted by the National Institute for Environmental Studies, between 1999 and 2005, the average annual decrease in oxygen levels was 4 ppm.

“But there are hardly any people around me who are seriously concerned about global environmental issues or humanity’s future. What about in your circles, Professor Kohama?”

“There are still very few, but I’ve noticed that people who have lived outside mainstream society or experienced life on the edges tend to be more aware of these issues.”

“It means stepping outside the human herd in the city and seeing things from the outside, doesn’t it? I believe venturing into the wilderness on a yacht, risking your life, is another way of stepping outside the herd.”

● 3. Delusional Earth ●

“My mother, born in 1909, once said something similar to what you mentioned. When she visited me in the U.S. while I was at a research institute, she sat quietly in the car for two hours, just looking out the window. Afterward, she said, ‘Japan can’t win against a country like this.’”

“Ultimately, we went to war without fully understanding our opponent, and we lost. We didn’t even realize how much we didn’t know. If we had observed the U.S., even just a little, like Mr. Kohama’s mother did, we probably wouldn’t have started the war.

“In the same way, modern society is damaging the global environment without truly observing or understanding the Earth, assuming we know what we’re doing. In the end, it’s us—who know so little about the Earth—who will be destroyed.”

“For example, the people who played key roles at the end of the Edo period, over 150 years ago, were the ones who went abroad and saw what was really happening outside Japan.”

“Back then, what you needed to learn was outside your country, but today, I think ‘outside’ means stepping away from the herd—from cities and society—to truly understand what’s happening to the Earth.”

“Today, we face many global issues—environmental problems, human rights violations, refugee crises—but at the root of it all is overpopulation. The population explosion we’re seeing now is a direct result of the Industrial Revolution.”

“Like the jellyfish outbreak I saw in the South Pacific, rats and grasshoppers die off when their numbers get too large. Similarly, the human population is growing much too fast.”

“The global population seems to be growing by 100 million every year. I read in the paper today that it’s already reached 6.75 billion.” (This conversation took place in 2008.)

“About 20 years ago, while sailing near Africa—the birthplace of humanity—I was surprised to know that the population had passed 5 billion. And 20 years before that, the world population I learned about in junior high school was just 3 billion.

“As the population keeps growing like this, it’s only natural for competition over land, food, and resources to increase, leading to conflicts.”

“Eventually, population control will become necessary, but I hope we never reach the point where we have to decide how many people should be eliminated, either in our country or others.”

“If it comes to that, I’ll have to escape on my sailboat to South America! I spent many years there and have a lot of friends.”

● 4. Farming Realization●

“I bought land north of Sendai and started farming, with 6,000 square meters of rice paddies and 1,000 square meters of vegetable fields.”

Professor Kohama, a bearded man working at the Institute of Fluid Science, has many interests. Besides farming, he enjoys flying light aircraft, oil painting, yachting (which we often did together), and more.

“I’m now approaching retirement, and this is my first experience with farming. Only now do I realize how much hard work it is to grow food—especially rice.

“It raised a simple question: ‘Why doesn’t anyone today have to go through this hardship?’

“In the end, machines and tractors powered by petroleum make farming as easy as hiring dozens of workers. That’s the conclusion I’ve come to.”

He thinks he has noticed the root of today’s affluent lifestyle.

“In short, if we look back at human history, there’s no way we could have lived such an easy life. Behind this ease, there was a slave-like existence—and in many ways, there still is today.

“In the past, Black people were enslaved in the U.S., defeated soldiers became slaves in ancient Rome, and farmers lived in near-slavery in old Japan.

“Today’s ‘slaves’ are machines that run on fuel instead of food. Assuming a human’s output is around 150 watts, the energy demands of modern machines mean each person uses 30 human ‘slaves.’”

This has given us leisure time and a comfortable life, but at the same time, various problems have arisen; as Professor Kohama emphasizes,

“As a result, we’re burning oil, emitting massive amounts of pollutants and carbon dioxide, and destroying the global environment, aren’t we?

“Today, young people are taking lives without any thought. I think this clearly shows how the environment around us negatively affects our mental state.

“In other words, we’ve created a world where we don’t need to work hard or sweat, but as a result, we’ve lost our sense of life’s value and its meaning. This can lead to suicidal or even violent thoughts.

“Being exposed to the harshness of nature, like on your voyage, is key to a healthy mind, but that’s not how we live in modern society, is it?”

“Since ancient times, humans have lived surrounded by nature, facing dangers and gathering food.

“As technology advanced, the need to live in nature decreased, and people began living in larger herds, forming towns and cities, which distanced us from nature, didn’t it?”

“The reason people are suffering today is the mismatch between the Darwinian timescale—spanning tens of thousands of years—and the technological timescale, measured in decades or centuries.

“While our bodies and minds evolve at Darwinian speeds, our environment has been rapidly transformed by science and technology, causing distortions in every aspect of our lives.”

“To my eyes, a major problem is that society’s common sense has drastically shifted as our way of life has changed. In the past, human herds were small, living within vast natural landscapes, and our common sense was closely aligned with the rhythms of the natural world. But today, in massive herds, we are far removed from that connection.

“After months of sailing alone at sea, I often felt uneasy about the gap between the town’s common sense and the natural world’s common sense that I had been living in.

“For example, the idea that ‘resources are limited’ is common sense on Earth, but in today’s society, it no longer feels like common sense.

“In towns, as long as you have money, you can keep buying whatever you want from stores. If a town runs out of resources, it can just bring more in from outside the town. Science and technology make that possible, don’t they?

“We’ve gotten used to consuming resources as if they’re infinite. Even though we know, logically, that resources are limited, we don’t really feel it on an emotional or physical level.”

“So, what should we do? What kind of lifestyle do we need in the 21st century to avoid damaging the environment?

“As you realized during your journey, the Earth is much smaller than you once thought, and the population has grown to 6.7 billion (as of 2008). Furthermore, we are steadily using up our resources.

“What can we do?”

“The first thing that comes to mind is ‘greed.’ We always want more, and when we get it, we want something else. That’s greed—the root cause of the environmental crisis.

“After successfully landing at Cape Horn during my voyage, I should have been satisfied. But greed took over, and I started pursuing even more difficult and dangerous challenges. It went on and on without end, and if I hadn’t stopped at some point, I might have lost my life. In other words, it’s important to change how you think and what you value.”

“That’s almost impossible...”

● 5. Shift in Priorities ●

“When I’m sailing or flying, I always say you have to ‘ground your own life.’ For example, you only realize how precious life is when you’re in a dangerous situation, but when you’re living in the safety of the human herd, you can lose that awareness.

“We used to live in constant battle with nature, but we don’t anymore. That’s why sports that seem dangerous are actually valuable.”

Does Professor Kohama mean that “grounding your life” is about “connecting your life to the Earth?”

“As you know, I’m fearless and also engage in somewhat risky sports like sailing, though my level is surely nowhere near yours.

“For example, when I’m flying, I often think, ‘What if debris gets in my eye?’ Losing eyesight in a plane would be disastrous.

“Each time I feel that kind of fear, I first sense the value of my own life, and then I recognize the value of others’ lives.

“The possibility of death is essential for maintaining a balanced mental state. Yet society tells us to avoid anything dangerous.”

“That’s right. Looking back on my voyage, there were insights I could only gain when facing real danger.”

“What you learned on your dangerous journey—the value of humanity’s sharpened wildness, sensitivity, and ancient instincts—is still essential today, even as we live in the comfort and safety of the human herd. Losing these qualities is a major cause of our environmental problems.”

“I believe the most important thing is our attitude toward nature. If we don’t realize we’re connected to nature, if we don’t understand that our lives are tied to the Earth, we won’t find a real solution to environmental issues—no matter how advanced green technology becomes.

“

But for those of us born and raised in cities, that can be difficult to understand.”

“That’s why I want you to share your journey with us through your writing and photographs. When I read your voyage story, I thought, ‘Wow, you pursued this at the risk of your life, and now you’ve recognized it.”

“But most people live in cities and have only urban experiences, so they don’t fully understand what I mean when I talk about my voyage.

“To understand beyond the world you live in, you need imagination. You have to be able to imagine beyond the boundaries of the human herd.”

“Exactly. You need to imagine beyond cities—that is, planet Earth itself—and even beyond your own time period.

“If we don’t do this now, we’re harming future generations, and we can’t allow that. We need to understand what we must avoid as humans—as primates at the top of the ecosystem.

“The reason we fail to understand this is, as you say....”

“It’s because we only see things within the human herd; we view Earth solely through a ‘city mindset.’”

“Today, human society is moving forward with tremendous speed and momentum, driven by the patterns of the past. Shifting in a new direction could take 100 or even 200 years.”

“It’s like a herd of animals moving toward the edge of a cliff. Even if those in front see the danger and try to stop, they’re pushed from behind and keep falling, aren’t they?”

“In the 21st century, things like the Olympics, World Expos, and the Nobel Prize shouldn’t hold the same importance they did in the 20th century. Yet the world still...”

“So, Mr. Kohama, what do you think will be most important from now on?”

“Well, this might sound a bit religious, but the words spoken to Adam and Eve in Genesis—’Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth’—don’t mean we should just keep multiplying.

“The point is that we were commanded to continue to survive. That’s what earthworms, frogs, and all creatures are doing down to the DNA level. It’s a game of survival; we are ordered to keep living. But we’ve eaten the forbidden fruit and created an environment where survival is no longer guaranteed.

“Even so, each of us must make a serious effort to ensure humanity’s survival. I believe it’s our mission to act immediately in this era of environmental crisis.”

“Until recently, people were seeking money and material wealth. But today, we’re beginning to focus on something more—like health and happiness. Mr. Kohama, can you imagine what comes next? I think it’s important to consider that. As time goes on, I believe people will start to recognize there’s a higher Purpose.”