The small Melchior Islands gather beneath a cloudy sky, their thick ice covering giving them a dome-like appearance. Periodically, the ice collapses into the sea, creating numerous floating pieces that often block the passage of small boats.

As seen in the photo, a line of black rocks is exposed along the boundary between the sea and the island, making it easier to distinguish between the islands and the dome-shaped icebergs.

Read this episode on the "Illusion Domes" page.

After escaping the strong current, Aomi continued toward the Melchior Islands, navigating through the Antarctic archipelago.

Low clouds hung heavily in the sky, but a narrow strip of light shone between the clouds and the sea.

It was a strange and puzzling sight—the island seemed to glow, but where was the light coming from? The sun's rays shouldn't have reached it through the thick clouds, yet it gleamed with a dazzling golden light.

Years later, I understood why: when the temperature of an ice-covered mountain is lower than the surrounding air, the air cools and creates a downdraft. This downdraft clears the clouds, much like in a high-pressure zone, allowing sunlight to break through. Even when thick clouds cover the sea, the sky above the ice-covered mountains can be clear, with sunlight streaming down.

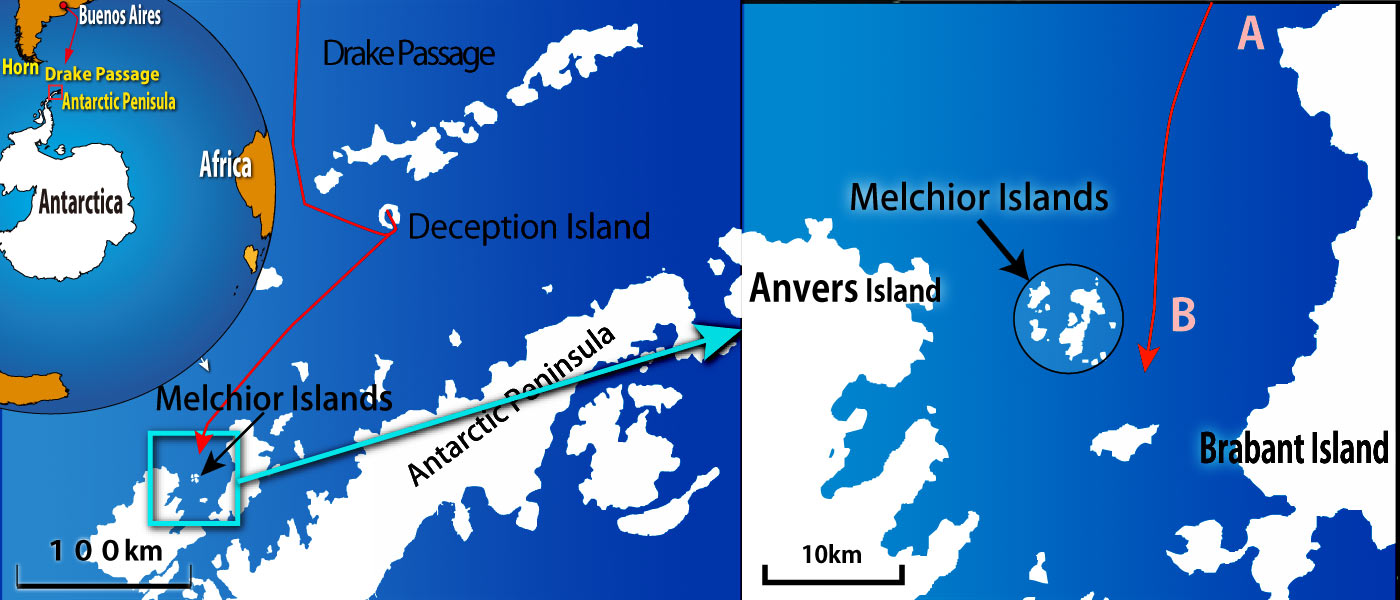

On the evening of the second day after leaving Deception Island, Aomi entered the waters between Brabant Island and Anvers Island, making her way toward the Melchior Islands. Both islands are large, stretching over dozens of kilometers. Aomi entered between the two islands at Point A on the right side of the map below.

Dusk was approaching, but I was determined to reach the Melchior Islands before nightfall—or at least try.

To the right of Aomi’s course, I saw what looked like dome-shaped icebergs close to Anvers Island. They could have been part of a peninsula extending from the island, or perhaps just icebergs.

As I've mentioned, the clarity of the Antarctic air makes it easy to lose your sense of perspective. That's exactly what happened this time.

Even though I was only a few kilometers from the Melchior Islands, I mistook them for a peninsula of Anvers Island or nearby icebergs, 15 kilometers away.

Aomi continued forward, and I failed to recognize the Melchior Islands to the right. (Point B).

I eventually realized my mistake, but it was too late—the sun had already set, and the sky was darkening.

The worst had happened. Navigating between islands at night was reckless, and I had no way of knowing what dangers lay ahead.

Waiting until morning wasn't a good option either. I hadn't slept since leaving Deception Island the day before and wasn't sure I could stay awake for another night.

With a seabed 400 meters below, anchoring was impossible. If I fell asleep without anchoring, Aomi could drift and crash into land. The situation felt hopeless.

*

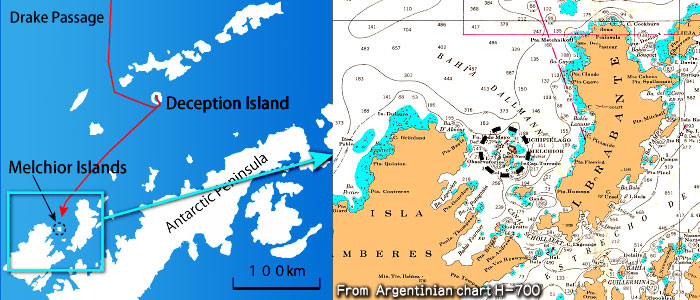

The map below shows the Melchior Islands situated between two large islands: Anvers Island to the west and Brabant Island to the east. Both islands stretch roughly 60 to 70 kilometers in length.

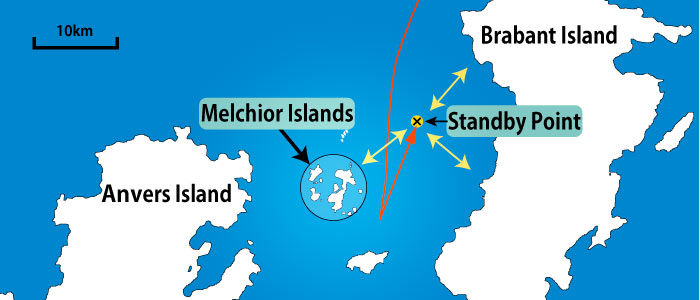

The right-hand section of the diagram below shows an enlarged portion of a nautical chart, with land in orange, sea in white, and shallow water in light green. The numbers on the chart indicate depths in meters.

The water between the two islands forms a bay that offers protection from wind and waves. However, the north side of the bay is open, so if a northerly storm occurs, wind and waves can enter directly.

Fortunately, there was no northerly wind that day. The bay was calm, with barely any wind or waves. Even if I fell asleep aboard Aomi, there was little risk of being swept away by the wind and running aground on the islands.

The current, however, was still a concern. Even without wind, Aomi could be carried away by it. The charts didn't show the current, and I couldn't find a clear description of it in the sailing directions either.

So, I found a point that was equally distant from the surrounding land on the chart, started the engine, and moved northward for about an hour. When I reached the spot and stopped the engine, a profound silence settled over everything, just as I describe in the main story.

Aomi was about five miles from any surrounding islands, so no matter which way she drifted, there was little chance of hitting land for over an hour.

To be safe, I set two alarm clocks for an hour and decided to take my first nap in 40 hours since leaving Deception Island.

Still, there was no guarantee that Aomi wouldn't run aground while I slept, as the positions of islands and reefs on the charts might be inaccurate.

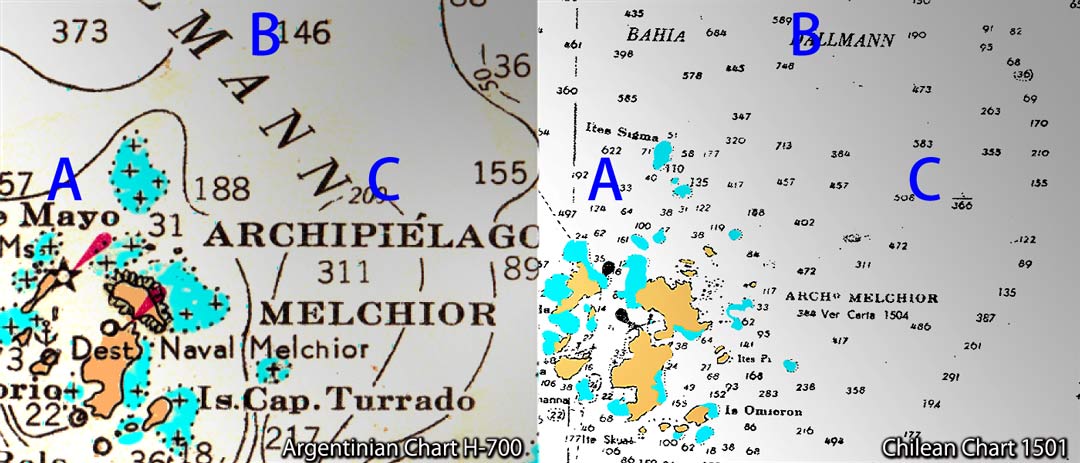

The diagram below compares the two charts I had aboard Aomi. The Melchior Islands are shown in the lower left of both. You’ll notice that the shapes of the islands and the shallow water areas are different.

The depth readings on the charts also vary significantly. Depths are sometimes shown in fathoms instead of meters, but both charts use meters in this case. (A fathom is about 1.8 meters or roughly one-thousandth of a nautical mile. A land mile is different from a nautical mile. The charts also show lighthouse marks, although the lighthouses were only temporary installations in the past..)

Now, let's take a closer look at the depths. Point A on the left chart sits on a 100-meter depth contour, but on the right chart, 622 meters is marked nearby.

Point B on the left chart is marked at 146 meters, while the corresponding area on the right shows 589 meters.

Further, the 200-meter depth contour runs near Point C on the left chart, while the same spot on the right shows 508 meters.

The seas around Antarctica remain poorly surveyed, leading to conflicting information. You can't fully trust charts in these waters—you never know where an uncharted shoal might be lurking.

I believed I had positioned Aomi in the safest spot, but there was still no guarantee she wouldn't run aground while I slept.

The background of this page is a photo of snow taken in the Antarctic.