Knowing nothing about the future and not being allowed to stop, you are sometimes forced to keep going in fear of your life. The period of sailing in the Chilean Islands, Patagonia, had been one of such hard days.

*

Aomi, heading for Cape Horn, was running in the Strait of Magellan with a specially made small sail (1/4 of the standard storm-sail) I called "super-storm jib." The width of the strait was about seven miles there.

On the water, waves are curling its peaks and breaking in green, transparent green. On a closer look, numerous ripples are on the waves' slopes. It is the sign of high wind.

"What a strong wind! Too strong," I thought in the spray passing my body from behind.

Honestly speaking, I am frightened so much. I pull the downhaul rope and lower all sails, but Aomi is still running with the force of the wind blowing the mast. Though there is no sail which works as a damper for rolling, the run is quite stable somehow. I go into the cabin, ignite a Primus burner, and start making lunch.

"Can I arrive at the next anchorage before sunset?" I muttered.

If it gets dark and I can see nothing in the deep darkness far from the town, Aomi will hit a rock or go aground.

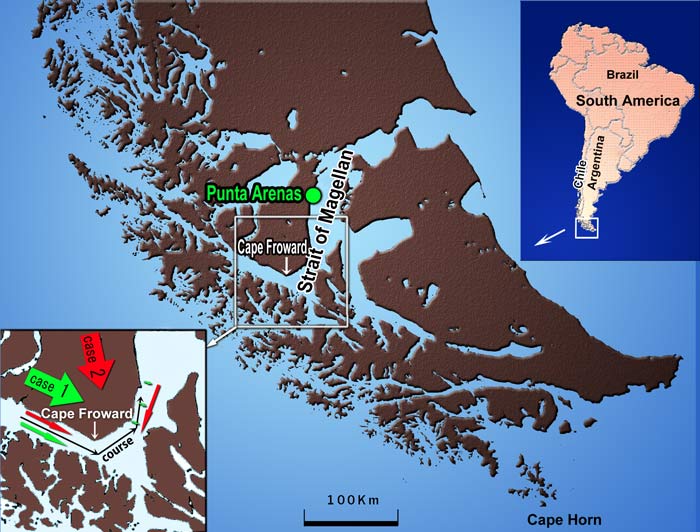

The black mountain in the photo, Cape Froward, is the southernmost of the South American continent. All the land south of there is a group of islands which continue up to Cape Horn (Horn Island).

After passing in front of Cape Froward, I want to change the heading from the East to the North and aim for Punta Arenas.

By the way, after Cape Froward, what is the wind like?

In a narrow strait between mountains, the wind tends to blow along the channel. I can imagine two possibilities after Cape Froward.

Case 1 (green arrows above): If the direction of the true-wind (the wind without the effect of land or mountains) is between the Northwest and the West, the friction with the ground weakens the wind. (Small green arrows)

Case 2 (red arrows): If the direction of the true-wind is between the North and the Northwest, a strong wind (a thin red arrow on the right) blows from the North-northeast. It will be a headwind.

If the latter case becomes a reality and the strong headwind blows, it is almost impossible to sail windward while tacking back and forth in the narrow strait. Furthermore, the wind must make the surface flow of water, which carries Aomi back.

Even if I could sail windward somehow, the sun would undoubtedly set on the way, and Aomi would run aground in the dark.

How long does the wind blow? What will the wind be after Cape Froward? How can I save Aomi?

Everything is unknown, and no one can help me, of course. Whom I can rely on is just myself, but I have deeply understood that I can do nothing in such a high wind.

In a narrow strait or channel between mountains, it is necessary to pay the closest attention to the direction of the wind. A slight change of the true-wind may cause a significant variation of the wind and put a small vessel into danger. It is essential to read geographical features from charts or maps and estimate the direction and the force of the wind beforehand.

Please help me translate the site.

Free checks on the writing by native speakers are needed.

E-mail

This is an episode of Aomi in the Strait of Magellan.

Do you know?

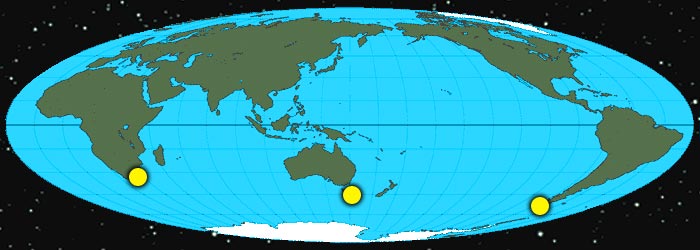

What is the southernmost of Africa?

- Cape Agulhas

- Cape of Good Hope

- Cape D.Lawley

What is the southernmost of Australia?

- Adelaide City

- Tasmania Island

- Bishop and Clerk Islets

What is the southernmost of South America?

- Cape Horn

- Diego Ramirez Islands

- Mar del Plata Island

What was the result? We do not know much about geography, do we? One of those which we don't know is Cape Froward, the southernmost of the South American continent.

Aren't the Diego Ramirez Islands the southernmost as answered above? No, I mean the southernmost of the CONTINENT! South of Cape Froward is just a group of islands.

Sailing in the Chilean Islands, Aomi had reached the Strait of Magellan. After rounding Cape Froward, Aomi was to head for Punta Arenas, a city having a population of about 120,000. I had had no chance to get food for more than two months because most of the islands in the Patagonian Archipelago were uninhibited. That was the main reason to visit Punta Arenas.

Until the Panama Canal opened in the 20th century, the strait had been a passage from the Atlantic to Pacific. It is shorter than rounding Cape Horn and protected from the high waves of the open sea. Punta Arenas, situated at the middle part of the strait, flourished as a base of coal supply in those days.

By the way, what is it like sailing between numerous islands in a small sailboat? The remarkable features of the strait are the breathtaking scenery and violent winds.

See the photo above. The land on the left is Cape Froward, the southernmost of the South American continent. You can see the top of the wave breaking and dancing. There are parallel lines of ripples caused by severe wind on the blackish slope of the wave. Furthermore, as you see in the photo, the breaking wave looks green― impressive transparent green!

The hoisted sail was only a tiny storm-jib of 2.4 square meters, smaller than a single bedsheet. Even with such a little sail, Aomi runs in the Strait of Magellan at a surprising speed. I pulled down the sail for fear, but Aomi was still running fast. The severe wind, blowing the mast and hull, was pushing Aomi to leeward powerfully.

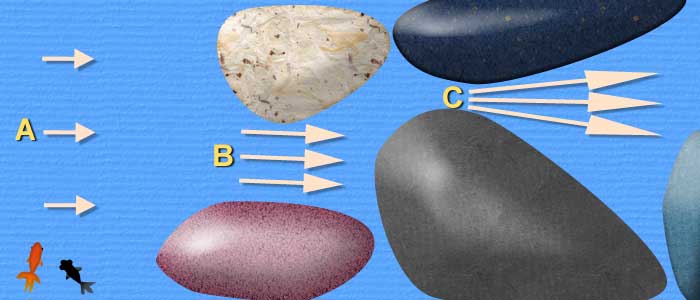

Why is the wind so strong in the Strait of Magellan? Try to imagine a shallow box with water and stones like below.

When water flushes from the left, the velocity at point B is higher than at point A because it is narrower at B. At point C, the speed of water is much higher than at B because the gap is much smaller. The speed of the flow depends on the width (cross-section) of the passage because the flow rate (e.g., litters per second) is constant.

Please notice that the velocity would be much lower without the stones. The speed at B and C will be the same as at A if there are no stones. Stones work as accelerators of the flow.

When the prevailing wind blows from the West, the islands in the image above work as accelerators as described above, especially where the strait is narrow. That is one of the reasons why wind is very strong there. It can be stronger than the wind at open sea. Sailing in such a wind must be a hard trial for yachtsmen.

The photo below is Habana Point in the Strait of Magellan. Washed and polished with the wave and swell from the Pacific Ocean, the rocks looked like weird white skeletons. How harsh was the wilderness that made the scenery? At a glance, I realized what kind of place the Strait of Magellan was. I never forget the strong impact at the time.

(Mouse over to show the map. )

Though the climate in the strait is so fierce, there are better days as well. On both sides of the strait, mountains continue, distant mountains are blue silhouettes, and high mountains have pale-white glaciers. Sometimes the sunlight spots the rugged slope of the mountain, and the rocks shine gold. In the next moment, clouds hide the sun, and the rocks become brownish violet at once. That was a mysterious scenery. Sailing in such a place in a sailboat must be a fantastic experience.

While sailing in the Strait of Magellan, I saw only two cargo ships. Though the importance of the strait is less today, some vessels, too big to go through the Panama Canal, still sail in the strait.

When you are sailing in the Strait of Magellan in a small sailboat, you had better to navigate only in the daytime even if you are more than two. You sail during the day and have to anchor in a bay at night.

(Mouse over to show the map.)

One day, Aomi stayed in a small bay called Playa Parda. There are snow-covered mountains in the back and weird violet-brown mountains in the front (see the photo above). The lines look like white-threads are waterfalls. Plants are scarce on the rock. The smooth surface of the rock, which looks like polished, tells us the severe climate there. As soon as entering the bay, I thought, "What an unearthly scenery it is!"

After dropping an anchor, I rowed a small dinghy to put a rope to the shore. You can't rely on just anchors in the region where strong winds prevail.

I looked for something to tie a rope to, but there was nothing suitable around there. What I found were just weeds or low thin trees. If there is nothing to fix a line to, the wind may blow Aomi away at night.

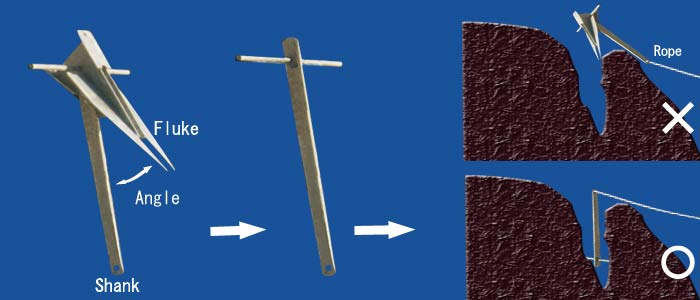

Then I recalled a technique to set flukes of an anchor in the crack of a rock, that I read in a book before. I rowed back to Aomi, get an anchor, and rowed toward the coast again.

Unexpectedly, the angle between the fluke and the shank was too small for the crack. The fluke came out of the crack when I pulled the rope.

I decided to put the whole anchor in the crack, but every crack around was too narrow for the anchor. After all, I took the anchor apart, removed the flukes, and made a cross shown below. (The genuine C.Q.R. Anchors cannot be disassembled in this way.) I named it "Rock Anchor."

By putting the cross in the crack, I was able to fix the rope on the coast firmly. There was no more danger of wreck due to the strong wind.

The growls of wind woke me up several times at night, but I felt at ease because of the rope between the coast and Aomi.

Please help me translate the site.

Free checks on the writing by native speakers are needed.

E-mail

Back to main page.